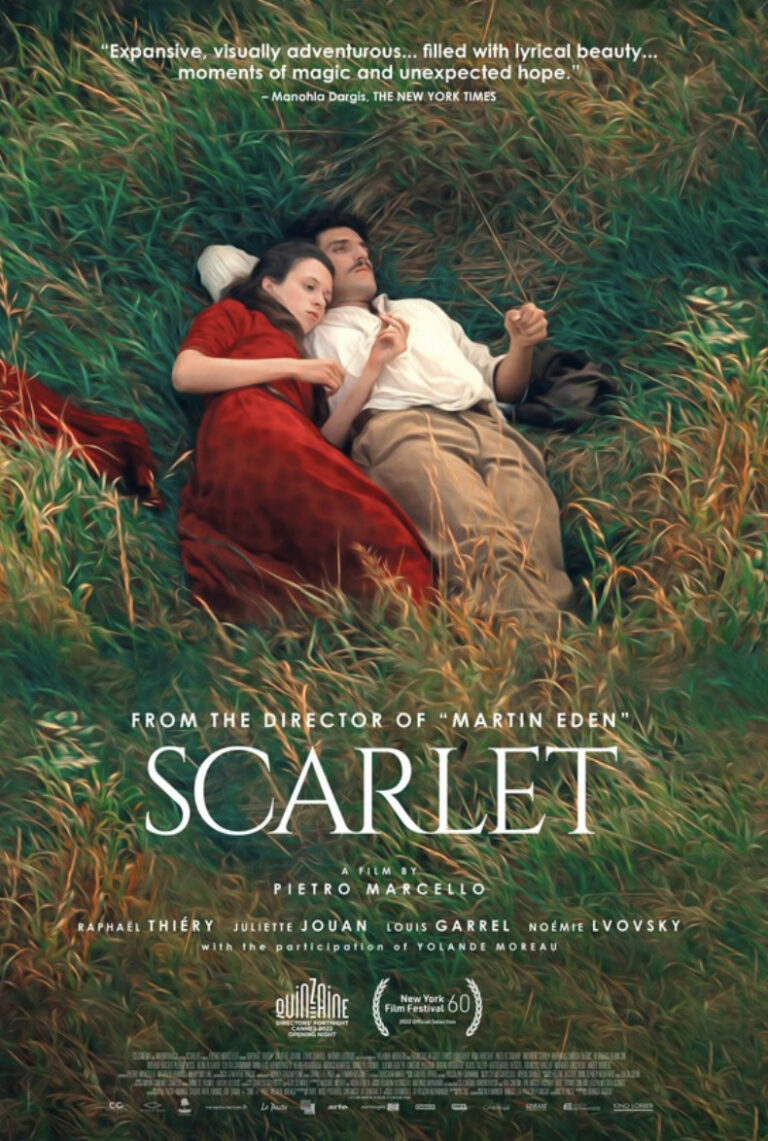

In 2019 “Martin Eden” made a splash in the arthouse film world. The Jack London based story of a tortured man in Naples craving to write prose with his working-class hands in post-World War II, established Pietro Marcello as a clever filmmaker with fresh ideas and salty nerve. In his follow up “Scarlet” another pair of artistic hands, yet very different, knocks on a door to a provincial French house, and travels even further back in the past.

“Scarlet” begins with a key sentence: “You can do so-called miracles with your own hands” says the quotation from Alexander Grin’s 1923 novel “Scarlet Sails”, from which the film is loosely adapted. The hands in question belong to a woodcarver named Raphael (Raphaël Thiéry), who returns home to a small village in Normandy in northern France in 1920 and finds himself a widower after serving in the frontlines of World War I. His hands are as rough as his furrowed face, as expressive as his presence. They know how to practice his profession and delicate enough to create a ship’s mast or play accordion to his infant child Juliette, who is placed in his arms to be raised, or create wooden sculpture of the child’s dead mother Marie.

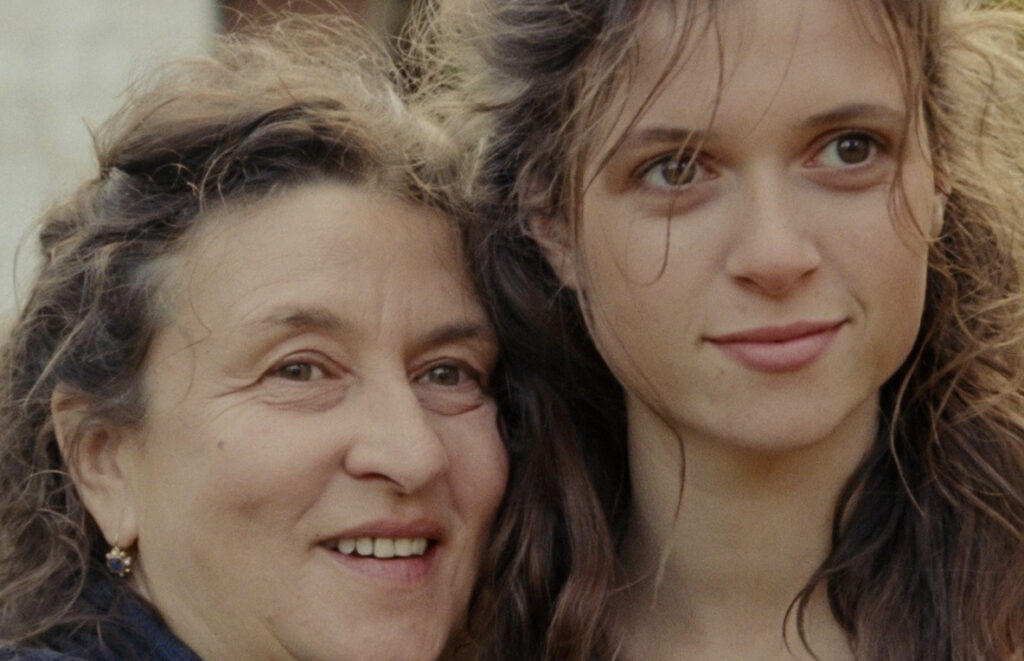

The first part of “Scarlet”, which follows this sullen and good-hearted man, is also the finest and the most coherent. The cinematography is pure and beautiful, evoking the senses by showing the gorgeous surroundings of provincial French life. In the second part we follow Juliette (newcomer Juliette Jouan), as she grows into a lonely young woman who seeks refuge in the nearby woods where she wanders and sings by the lake. Here she meets a witch (Yolande Moreau) who prophets her away from the village.

But unlike the protagonist in Pietro Marcello’s excellent breakthrough film “Martin Eden”, this character doesn’t break with her past. She stays and tries to find happiness where she is, having a strong bond with her father and Madame Adeline (Noémie Lvovsky), with whom they live. Both Martin Eden and Juliette grew up in working-class environments, and both experience strong love. The difference is that you get a sense of who Martin Eden really is as you dive into his inner life, feeling his agonies, his yearning, his pain, and his complexity. With Juliette you only scratch the surface.

She falls for Jean, a young pilot (an always great Louis Garrel) who literally falls from the sky in a plane to sweep Juliette of the feet. Unlike her father who is a rock and knows who he is, Jean is unstable, a modern wanderer who doesn’t know where he belongs and doesn’t come into her life to save her. On the contrary, she is the one who makes the first move and looks after him. Although Juliette is an outcast and bullied in the village – she is called “the nut from the Wretch Farm” – she is a feminist character, and the film is a sort of anti-patriarchal statement. She is raised by a community of women (and her father) which has created a strong sense of matriarchy. Juliette had the opportunity to study in town but the decision to stay in the countryside is her own. It is not a sacrifice. In Alexander Grin’s novel “Scarlet Sails” she goes from man to man and gets married. Here the core of the story is her independence and the relationship with her father.

As in “Martin Eden”, Pietro Marcello has gracefully and impressively interwoven archive footage with unforgettable working-class faces, creating a dialogue with the past in which the film takes place. Pietro Marcello has gained admirers for his many high-profile, Italian documentaries, among them the collective “Futura” he made with Alice Rohrwacher (“Happy as Lazzaro”) and Fransesco Munzi (“Black Souls”). Three years ago he moved to France – he wanted to be close to his daughter who lives in Paris.

Without a network of contacts in the film world and not speaking French, Marcello found himself starting from scratch making “Scarlet”. A film that is rooted in the local French culture of a peasant community and folklore.

His observant foreign eyes could have been an advantage but here it seems to be a disadvantage. “Scarlet” stumbles. Way too often filmmakers struggle to pull it off in other languages and cultures, getting lost in translation as their films loses credibility. Some scenes in “Scarlet” however feel sincere, as realism is interwoven with a touch of magic, kindred with the films of Alice Rohrwacher – a director that in my opinion is the front figure in contemporary Italian cinema and heir to the Italian master directors, while other scenes feel forced. Like the use of musical elements – sometimes Juliette burst into song inspired by the French director Jacques Demy (“The Umbrellas of Cherbourg”).

The stilted editing breaks the weightless fluidity and freshness that occasionally appear, and the mix of reality, fantasy, and poetry is not always convincing. The beautiful original score is composed by Oscar-winning composer Gabriel Yared (“The English Patient”) and is organically married to the visually arresting images of the remote universe captured by cinematographer Marco Graziaplena. This idyll of provincial woods and fields wants so much to echo secrets and history, magical realism and sensual appetite. Sometimes it does. Sometimes it leaves you wanting to taste more.

Grade : B-

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.