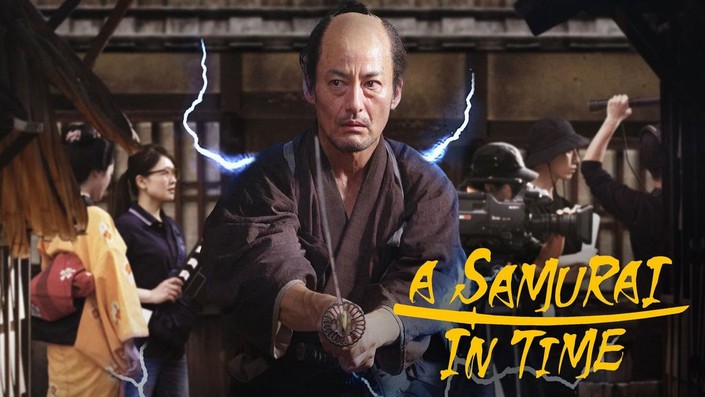

The fantasy comedy picture A Samurai In Time, directed by Jun’ichi Yasuda, focuses on the time travel experience of Kosaka Shinzaemon (Makiya Yamaguchi). He is an Aizu samurai from the Edo era, who is struck by lightning and is transported to the film studios of 2007 Japan. It will take some time for this 19th century man to adapt to a new epoch, learning the craft of filmmaking and gradually becoming a successful kirareyaku (a stunt performer specialised in being slashed and spectacularly dying on screen). As he adjusts to this new life, he bashfully becomes fond of assistant director Yuko Yamamoto (Yuno Sakura), he follows the guidance of sword fighting instructor Sekimoto (Rantaro Mine), and works continuatively with star actor Kyotaro Nishiki (Tsutomu Tamura). Things take an unexpected turn when he is offered a supporting role by Kyoichiro Kazami (Norimasa Fuke), who he discovers to be connected with his past.

140 years have passed from the Tokugawa Shogunate and many cultural norms are foreign to Mr. Kosaka. He was raised with The Analects, the Confucian philosophy, that had the aim of forging ethically-cultivated men with consummate integrity. Thus, he is extremely sensitive in recognising these values in others, even if they defy the conventions he was accustomed to. For instance, besides developing affection for Yuko, he highly respects her dedication to her job, commenting “Miss Yuko is like a praiseworthy samurai.”

The movie, part of the 2025 Japan Cuts, is beautifully shot, both when it comes to the action scenes, as well as the more intimate moments, that provide a profound connection with the characters. When the two opponents of an upcoming duel are sitting on a porch, the shot recalls a scene from Yasujirō Ozu’s Late Spring; of two rocks and two fathers with overlapping triangle shots. In Ozu’s film, the two fathers discussed how they raised children who would then go off to live their own lives. In A Samurai In Time the two warriors are silent, but their quiet immobility is incredibly expressive.

Above all, Jun’ichi Yasuda pays tribute to the Jidaigeki genre, i.e. the Nipponic period dramas set before the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Insights on their history is sprinkled through some lines of dialogues, like when Yuko says that during her childhood she would watch television series such as Zenigata Heiji and The Unfettered Shogun.

A Samurai In Time boldly celebrates this cinematic genre that has declined in popularity over recent years, unable to attract the younger generation. The film was warmly received at Montreal’s Fantasia Film Festival and eventually around the festival circuit and the box office, selling out 500-seat screenings at multiplexes. When it comes to accolades, the film also conquered the Best Film Award at the 48th Japan Academy Film Prize ceremony. This represents a sense of vindication and comeback for low-budget independent films, that break the stigma of anachronisms. Even more so, when one acknowledges the labour of love that went into the making.

In our exclusive Cinema Daily US interview, Jun’ichi Yasuda described how he worked with a small crew of 10 people, and it was reportedly the first time such an indie production was granted the use of the famous open-air set at Toei Studios in Kyoto. Furthermore, some actors went beyond the Stanislavski method, like Yuno Sakura who played the AD in A Samurai In Time, and simultaneously worked as a real assistant director on the film. In all of this, while making the movie, Jun’ichi Yasuda had recently lost his father and took over the management of his rice fields to pay respects to his heritage. Therefore the making of this picture was somewhat of a time-machine for the filmmaker, who was coalescing moments of his childhood with his present as an artist.

Back To The Future is the all time Western time-travelling classic, that has triggered viewers to question themselves on the “what ifs” of their lives, in relation to past choices. A Samurai In Time does exactly the opposite, by making audiences ponder upon a past that has been glorified, by looking at it through a future-present perspective. Furthermore, it makes us analyse, under the microscope, the current time we are living in. The protagonist feels Japan has gone a long way, not simply with technology, but also because a delicious cake is something available to all and not just to a select few. At the same time, the old samurai code ethic, is seen as an example that should be considered also during the 21st century, making this film a highly existential experience.

Final Grade: B

Check out more of Chiara’s articles.

Photo Credits: IMDb