Bastille Day is the French celebration that marks the moment in history when the people uprose against the aristocracy; this revolutionary act led to the proclamation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Despite it being a quintessentially francophone feast it is heartfelt all over the world, even in the USA.

For instance, if you happen to be in New York City, the French Institute Alliance Française offers a celebration at the SummerStage in Central Park, featuring live jazz, a dance party and the screening of the the 2020 French comedy My Donkey, My Lover & I (Antoinette dans les Cévennes).

But if you are planning to celebrate it at home, a real treat would be to feast with a good selection of Bordeaux, a baguette, some Camembert and Roquefort, whilst watching a French motion picture. Here are 14 films to celebrate July 14th that range from the classics of the French New Wave, until our day and that possess a timeless je ne sais quoi:

The Grand Illusion (La grande illusion, 1937)

Jean Renoir’s masterpiece accounts the economic interests behind wars, in line with the 1909 book The Great Illusion that inspired it, written by British journalist Norman Angell. The film is a powerful, humanistic and multicultural parable, as it harshly criticises nationalistic ideologies and divisive politics.

Children of Paradise (Les Enfants du Paradis, 1945)

The film cherished by François Truffaut, as much as by Marlon Brando, is known as the French answer to Gone With The Wind. Although Children of Paradise was shot during the final years of World War Two, director Marcel Carné — in line with his poetic realism — sets it in the theatrical world of Paris of the 1830s, where a courtesan is wooed by a mime, an actor, an aristocrat and a criminal.

The 400 Blows (Les quatre cents coups, 1959)

This milestone of the Nouvelle Vague launched the career of Jean-Pierre Léaud, as he portrayed the shenanigans of the rebellious Antoine Doinel, neglected by his parents. Considered one of the best French films in the history of cinema, The 400 Blows was both a semi-autobiographical reflection of its director, François Truffaut, and a harsh critique to the treatment of juvenile offenders in France at the time.

Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960)

Jean-Luc Godard’s most celebrated film, was also his first feature-length work and represented Jean-Paul Belmondo’s breakthrough, acting alongside the ingénue from Hollywood, Jean Seberg. Breathless was groundbreaking, because it defied cinematic conventions, with a contradictory character, an authentic style that would nevertheless refer to imaginary models of cinema, and the famous introduction of jump cuts that annihilated the identification process of viewers with the characters.

Jules et Jim (Jules and Jim, 1962)

François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim epitomises women’s liberation from patriarchal stereotypes. The femme fatale, Catherine, who has a ménage à trois with Jim and Jules, uses her seductress charm to assert a feminist stance, rejecting preconceptions and praising a nonconformist lifestyle. The film became a manifesto and a rupture with the conventions of its time and — with the impressive performances of Jeanne Moreau, Oskar Werner and Henri Serre — it does great justice to the novel of the same name by Henri-Pierre Roché, which inspired it.

Playtime (Playtime, 1967)

Jacques Tati reprises his role of Monsieur Hulot, from his previous films Mon Oncle and Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot. The actor-director’s visual comedy was distinguished by the use of elaborate sets, along with an innovative use of sound. The themes explored by Playtime in the Sixties, still resonate today, first and foremost, the depersonalisation of the metropolises. One may travel worldwide, but all capitals look the same, since public spaces conform to a passive vision that isolates the individual instead of bringing him closer to others.

Camille Claudel (Camille Claudel, 1988)

This French biopic retraces the love story between sculptor Auguste Rodin and his pupil Camille Claudel, who became an established artist at a time when women were not allowed to enrol in leading art schools. Isabelle Adjani and Gérard Depardieu, under the direction of Bruno Nuytten, have great chemistry in Camille Claudel, bringing to the silver screen the tormented liaison between the two most celebrated representatives of modern sculpture.

La Haine (La Haine, 1995)

Mathieu Kassovitz’s outstanding debut film, La Haine — that stands for hatred — was a harrowing call for awareness on the unfair ghettoisation of immigrants in France and the violent abuse of power by the police. After almost three decades, the topic is still relevant in today’s society. Besides the social message, the film stands the test of time for its black and white footage and the superlative performances by Vincent Cassel, Hubert Koundé, Saïd Taghmaoui, Abdel Ahmed Ghili and Marc Duret.

The Chorus (Les Choristes, 2004)

The feature directorial debut of Christophe Barratier — nephew of Jacques Perrin, who starred and produced the film — was a real phenomenon in France: a box-office champion that was selected as the French entry for the Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Original Song (Vois sur ton chemin, listed as Look to Your Path, composed by Bruno Coulais). Gérard Jugnot brings great humanity to the character of Clement Mathieu, a failed musician who is hired as director of the choir in a French boarding school for troubled boys. Thus, the inspirational and aggregational power of music is unleashed in The Chorus, throughout a beguiling music score.

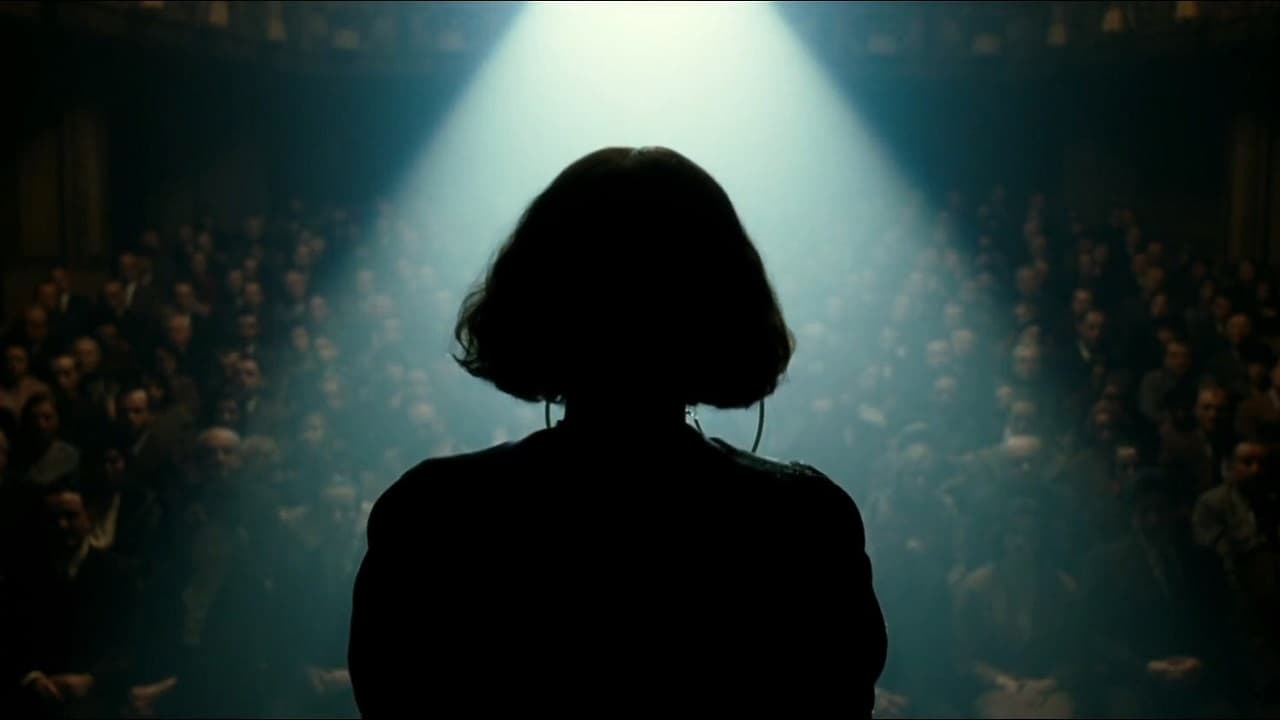

La Vie En Rose (La Môme, 2007)

The biopic about Édith Piaf, played majestically by Marion Cotillard, retraces the singer’s life going from rags to riches. Director Olivier Dahan ingeniously chronicles the narrative through a non-linear series of key events of La Môme — meaning “Little Sparrow,” Piaf’s nickname for her petite body. In La Vie En Rose memories run freely, like in a stream of consciousness sonata, where life intertwines with art.

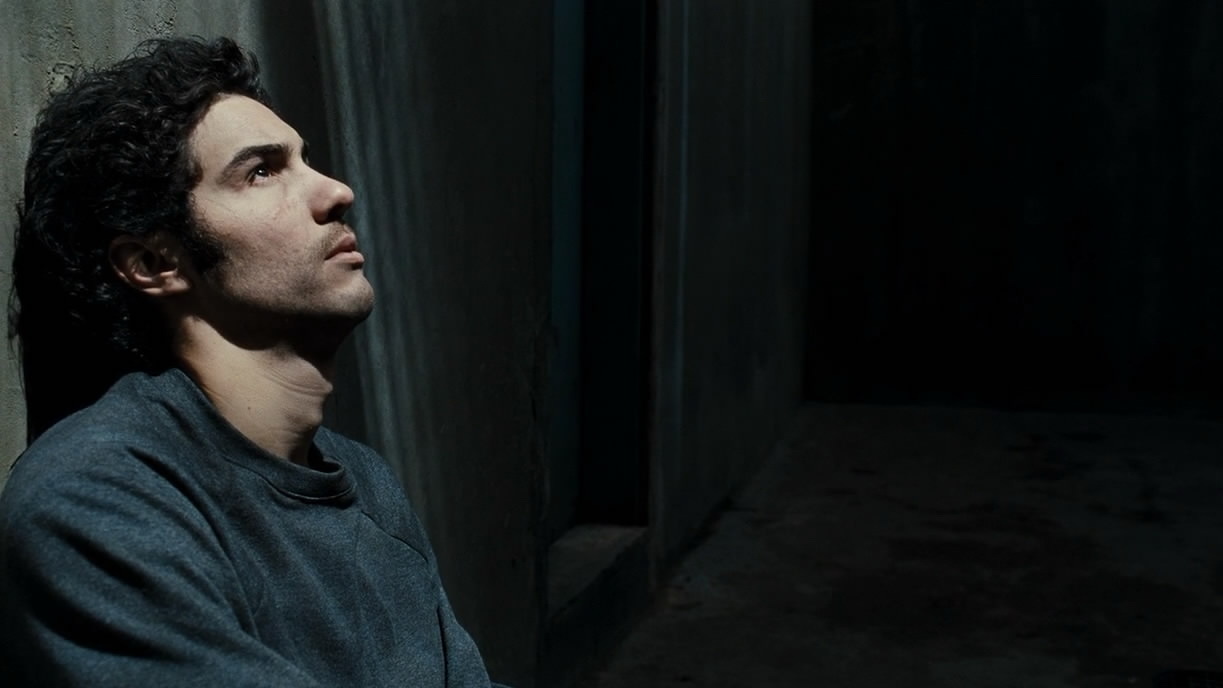

A Prophet (Un prophète, 2009)

The film written and directed by Jacques Audiard, that brought into prominence French-Algerian actor Tahar Rahim, potently depicts the social hierarchy inside prisons. The complexly violent thriller follows Malik’s personal growth, but also the way his latent criminal spirit is nurtured by the life behind bars, to the extent that he becomes a boss at it. In A Prophet, jail becomes the allegory of the way the environment that surrounds us moulds our spirit, and this guerrilla space has its own moral code and ranks, where one can choose whether to survive or thrive. Malik opts for the latter.

Amour (Amour, 2012)

This is one of the most heart-wrenching and excruciating romantic films, directed by Michael Haneke, starring Jean-Louis Trintignant, Emmanuelle Riva and Isabelle Huppert. Amour portrays love in the old age, as Anne and Georges have built a harmonious life together that gets shattered when the woman is hit by a stroke that paralyses her, while her husband bravely faces her disability. Georges perseveres in nursing Anne on his own, despite their daughter wants her to go into care. The octogenarian pianist couple, thus conducts their last concerto in unison.

My Life As A Zucchini (Ma vie de Courgette, 2016)

On this day in which we celebrate French cinema we could not forget the younger generations, and this stop-motion animated comedy-drama will delight kids and adults alike. Claude Barras introduces us to Courgette, who finds himself in an orphanage with peers who were raised in difficult conditions. Despite it may come across as a politically correct story, it has such soulfulness and knowledge of the subjects brought to the screen that it truly leaves viewers dewy-eyed. My Life As A Zucchini, received acclaim for its emotional tone and story, and was selected as the Swiss entry for the Best Foreign Language Film and was nominated for Best Animated Feature Film at the 89th Academy Awards.

Les Misérables (Les Misérables, 2019)

Not to be confused with the musical inspired by the Victor Hugo novel, in this case Les Misérables, “the wretched,” are those living in the banlieues. Renamed the “New La Haine,” the feature debut of the director born in Mali — Ladj Ly — is set in Montfermeil, a commune in the eastern suburbs of Paris. This is the place where the filmmaker grew up, amongst dirty streets, bare gardens, and the remains of abandoned social housing barracks. The storytelling initially comes across as an investigative documentary or a journalistic reportage, but it then transforms itself into a merciless parable of our corrupted society where it is difficult to distinguish the villains from the heroes.