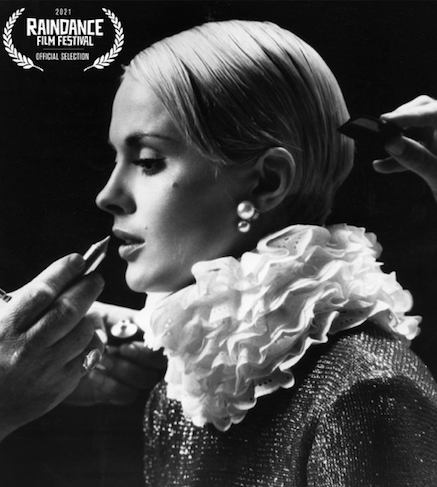

Raindance, the largest independent film festival in the U.K., serves as platform for the international premiere of Jean Seberg: Actress Activist Icon. This documentary — produced by Emmy nominated and award-winning filmmakers Garry McGee, Kelly Rundle, and Tammy Rundle — is the first in its kind to delve into the private side of the Marshalltown, Iowa native.

The motion picture is very dutiful in retracing the biography of the most beautiful and preyed upon actress in film history. Jean’s professional journey began when she was just a teenager, in a tiny unknown American town, and was selected among 18,000 applicants at the age of 17 for Otto Preminger’s 1957 Saint Joan.

Throughout the documentary, footage of her interviews and most notable performances are intertwined within the narrative, and include scenes from Hollywood movies such as Lilith, Paint Your Wagon and Airport. Needless to say that there is also Jean-Luc Godard’s French New Wave film Breathless (À bout de souffle) — since it was a career changer for the stars and stripes ingénue, who eventually became the darling of European cinema.

The film dutifully retraces also all of Seberg’s marriages with French lawyer François Moreuil, French novelist and diplomat Romain Gary (who was 24 years her senior and with whom she had a son, Alexandre Diego Gary), American-French director Dennis Berry, and Algerian Ahmed Hasni (with whom she went through a form of marriage although she was still legally tied to her third husband).

Besides her extraordinary career as an actress and unbridled personal life, the film highlights Seberg’s off-screen civil rights activism and how her support of the Black Panther Party made her a target of the F.B.I.’s COINTELPRO, through a media defamation strategy that was ordered by J. Edgar Hoover to “neutralise” Seberg.

The secret service instigated the rumour that the father of Jean’s second unborn child was a “black militant,” with whom the actress had had an affair despite being married to her second husband. The story that broke out on Newsweek magazine and multiple newspapers, across the United States, caused such a shock to Seberg that it sent her into premature labour three months early. The child, Nina Hart Gary, lived for two days before dying; her mother took her dead daughter to her hometown for a funeral with an open coffin service, to prove that her infant was white and the press accusation was slander. This circumstance affected Seberg’s emotional, psychological, and social well-being, initiating a downward spiral that lead to her mysterious and untimely death in Paris.

Another element, on which the film sheds a light upon, is how Jean Seberg became an icon of style.

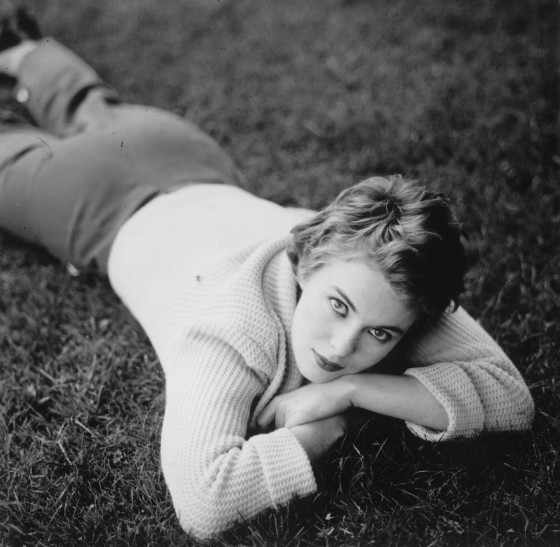

Women admired and emulated her fashion choices. What became legendary was her pixie haircut — “la Seberg coup” — that was copied by many actresses through the course of time, including Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby.

The archival research behind this cinematic chronicle is impressive, as much as the on-camera interviews with Jean’s family, like her sister Mary Ann Seberg and former husband François Moreuil; friends and film colleagues, such as Mylène Demongeot and director Nicolas Gessner; film historians and civil rights scholars, including former Black Panther Party leader Elaine Brown.

However, the visual assembling of this material is at times incongruous: if lap-dissolves lift the storytelling, the split-screens and powerpoint-styled fade-outs pull it down. Nevertheless, the film is praiseworthy for the extraordinary dissemination process it provides in bringing to the silver screen the many sides of one of cinema’s greatest icons.

Final Grade: B/C