French-Tunisian director, screenwriter and producer Nadia El Fani has always been an advocate of freedom of expression throughout her cinematic work. She was born in Paris and moved with her family to her father’s homeland, Tunisia. El Fani began her filmmaking path as assistant director to the likes of Roman Polanski, Nouri Bouzid, Romain Goupil and Franco Zeffirelli. Eventually she created the production company, Z’Yeux Noirs Movies, to make her own films. Later in time, she was ignited with the title of Chevalier de l’Ordre National Du Mérite, which is awarded by the President of France for distinguished civil achievements.

An adamant feminist, atheist, communist and supporter of secularisation, Nadia El Fani has gained recognition in the festival circuit but has also confronted fierce attacks from Islamists. The film that triggered most controversy is Laïcité, Inch’Allah! (prior titled Neither Allah Nor Master, Ni Allah Ni Maître), that screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 and won le Grand Prix International de la Laïcité.

Her latest documentary, Capitale Parenthèse, was presented at the 33rd Carthage Film Festival. In that occasion Nadia El Fani was also part of the jury for feature and short documentaries with Jury President Marie-Clémence Andriamonta Paes, and jury members Claire Diao and Souad Labbize.

In this Exclusive Interview Nadia El Fani shares her creative process in conveying the themes she has at heart:

Q: In all your films you’ve always been an advocate of liberty and you were an active character of the storytelling, whereas in Capitale Parenthèse you are more in the background. We principally follow your interior monologue. How did this cinematic stream of consciousness come to life?

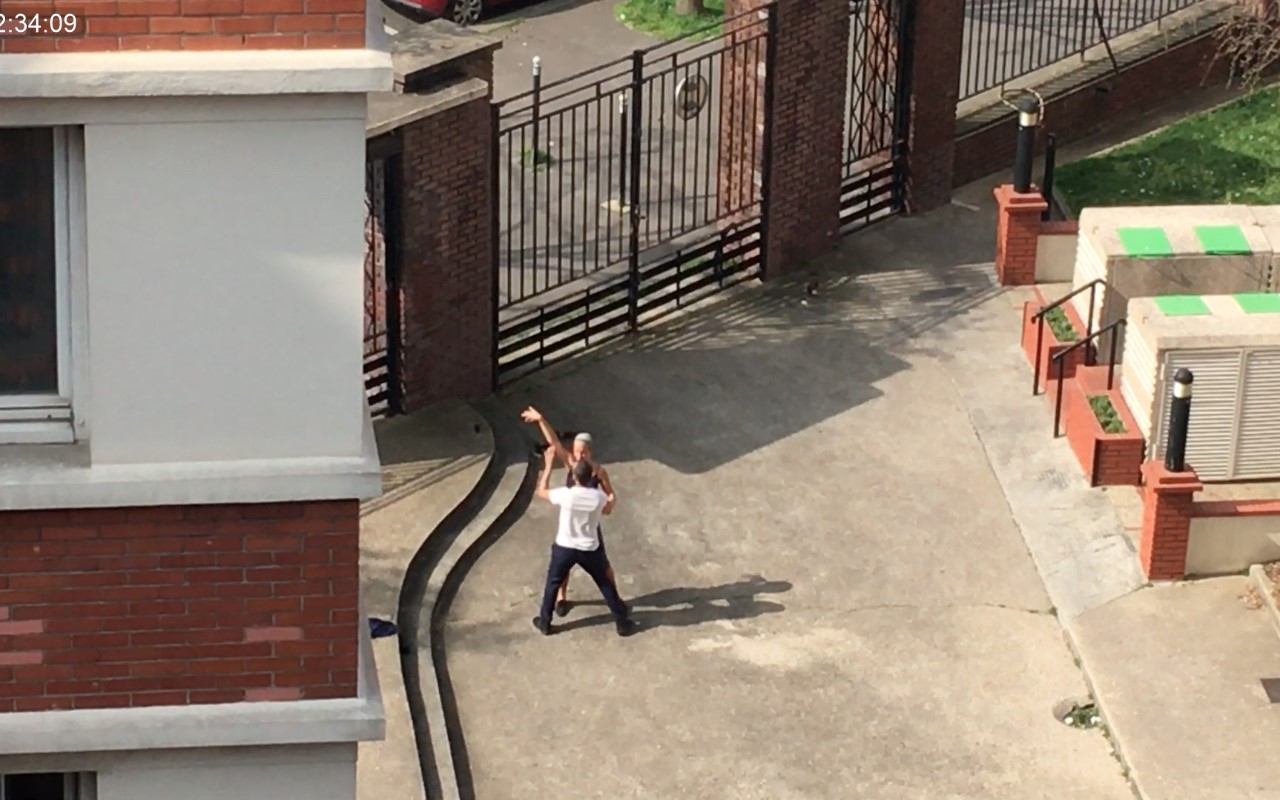

NEF: When I was a child I thought I was the one being filmed, that someone could see everything I did. And it wasn’t God, since my parents raised me as an atheist. It wasn’t a paranoid delirium either, I was never afraid. But it was like an awareness that we are always being observed in our actions, so I always wanted to make my own awareness visible to others: I wanted to share my vision of the world. That is the very megalomaniac side of any creator in my opinion, who believes that what he or she thinks is interesting for others. So when lockdown arrived I dreaded this moment of deprivation of freedom. It was the worst thing that can happen to me: not being able to do what I want when I want. I think that directing a film is always about talking about yourself. Sometimes I appear on screen to join the people who are fighting for the causes I want to support, like I did in Laïcité, Inch’Allah! and Même pas mal. Sometimes I overcome the shame in chronicling a love that has come to an end, like in Capitale Parenthèse. This movie is about total freedom. At the beginning I just decided to film daily what I saw from my windows and the empty streets around my house: the unusual views of Paris in a popular neighbourhood. I also recorded radio broadcasts, randomly during the day. I had no idea of what I was going to do with it all, I just wanted to exorcise this frustration of not being able to shoot a film I had been preparing for months. When lockdown ended I had everything ready to be edited, the footage was divided into categories and I thought I should put it all together somehow. I decided to narrate with a voice over the more intimate truth that did not appear on screen: my breakup. And coming from this place of love gave me an even more poetic, nostalgic and lighter meaning to my images, as well as my desire to communicate with the outside world.

Q: You include the letter by Annie Ernaux to President Macron in your storytelling. What are the topics that she brought up that resonated the most in the way you experienced lockdown?

NEF: Annie Ernaux, the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2022, is an author whom I particularly like. Her intimate stories, which are eminently political, represent everything I seek to do with my films. I do it in a more erratic way because I do not seek perfection, it bores me personally. Her letter is directly addressed to Macron during a very delicate time, France had just experienced the social justice movements of the yellow vest protests. And Annie Ernaux, committed to her ideals, takes her pen to remind us that it is the poorest who hold the country together by continuing to work in supermarkets and hospitals, by delivering meals, picking up the trash and so on. Her way of always taking sides with those who suffer but who resist triggers my admiration. We were all separated without having a say in the matter and she found a way to unite us in spite of it all.

Q: As we see in Capitale Parenthèse, you had to cancel the production of your new film in Tunisia because of the pandemic, but somehow another documentary came to life. At one point you describe filming as an act of resistance and survival, how much of this approach comes from your family origins?

NEF: Of course my personality was shaped by growing up amongst communist militants, in this young country which had just emerged from independence and which had already chosen the single party. My father for example could not come on holiday with us — my mother was French and we visited our grandparents in France every summer. But he could not obtain his passport for two years. Therefore when I’m faced with injustice I always react! The revolt begins with resistance; finding a way to subvert the established order. What I had the power to do during lockdown was to go out in the streets, perhaps a little further than the authorised distance and for longer than the allotted time. When I really couldn’t stand it anymore I would ride my motorcycle and put the GoPro on my helmet to film the streets empty of life.

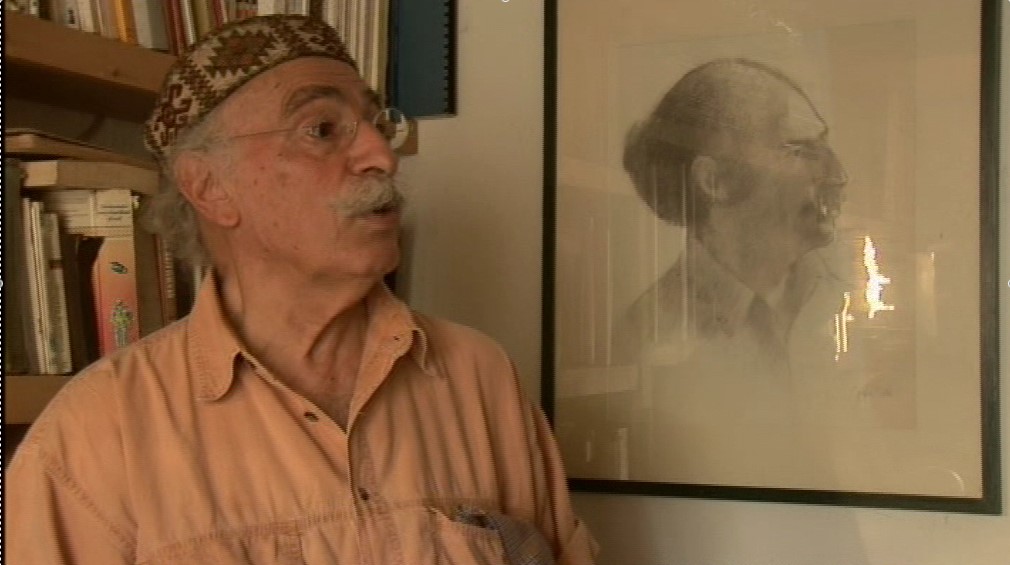

Q: In one of your previous films, Ouled Lénine we learn about your father Béchir El Fani, who was one of the leaders of the Tunisian Communist Party. At the end of that documentary he is the only interviewee who still considers himself a communist today. In contemporary society communism has been given many labels, what should young generations know about what it meant to be a communist in your father’s time and do you think those ideals still stand today or they’ve perished?

NEF: My father, who is 90 today, still lives in the house where I filmed him in Sidi Bou Saïd. In the film he says he’s still a communist, he’s earnest about his ideals. But he also says that for him the most important are the (French) Republican Principles “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” [Liberty, Equality, Fraternity] that I think are still relevant and unfortunately unapplied, neither in France nor elsewhere…So the fight continues!

Q: You are a fighter at heart, as demonstrated in your previous film Même pas mal (No Harm Done), where you show yourself battling cancer and the hate of Islamists who attacked you for advocating a separation between religion and state in Tunisia. You received death threats and legal complaints, risking 5 years of imprisonment following the release of your film Laïcité, Inch’Allah! (Secularism, God Willing!). What do you remember of that period and how has the situation evolved today for you?

NEF: When the Islamists attacked me on Facebook, after the world premiere of my film at the end of the Doc Festival in Tunis, I was already in chemotherapy. It was in April 2011, barely four months after the January 14th 2011 Revolution. They attacked me because I dared to declare to the journalist who interviewed me on television that I did not believe in God and that I was at war against political Islamism. The film at the time had the title Ni Allah, Ni Maître, like the slogan Neither Allah, Nor Master of the anarchists of the beginning of the last century. Then the French distributors of the film asked me to change the title to Laïcité, Inch’Allah!, but in the USA it is distributed by Icarus Films and it is under the title Neither Allah, Nor Master. The film went to Cannes but not in the official section, and at that point the Islamists went wild. But I have to say that in the face of adversity I always stand up, I act like I’m not afraid, like nothing gets to me. I don’t know if it’s recklessness. I simply know that I never want to give in, so I face whatever I have to. That’s how I analyse things. I always want to demonstrate that we can resist, there is no fatality. Today the criminal complaints (they were 6 in total!) have finally been dismissed in 2017 after more than six years of legal battle in Tunisia and I can finally go back there. Despite all of this, it’s been more than 10 years that in parallel to my documentaries I’m trying to make a fiction film. I have already presented scripts twice to receive a grant in Tunisia, after having received prizes for the scripts in other places, but so far I haven’t received any help from Tunisia. Nevertheless I continue to introduce myself as a Tunisian filmmaker!

Q: When we watch you in your films, your approach to life and death seems fearless. Do you think it’s connected to your name, that as you explain, in Arabic means “mortal: the one that burns until nothing is left”?

NEF: I love this question! Yes I believe the meaning of my name has something to do with it. I do not fear death. When I was young, I wanted to kill myself. But with a particular staging. I had a chaotic love story with a girl when I was 20 years old, it was 1980 in Paris with drugs and all that, I wanted to make movies and I didn’t know how to go about it. She was an actress and every night we imagined a new staging, so that we could find our bodies intact, we imagined ourselves having an overdose at the top of the Mont Blanc mountain or in the Sahara Desert. But it was very joyful, not morbid at all! Finally I went back to Tunisia and I started working on foreign films that were shot there as an assistant director. The first film I worked on was Misunderstood by Jerry Schatzberg with Gene Hackman. I told myself that starting like that was bound to be wonderful! In fact, I actually love life profoundly!

Q: Music is a very important element in all your films. In Capitale Parenthèse you reprise the song ‘L’Internationale‘ that was present also in Ouled Lénine and you include ‘Prohibition’ by Brigitte Fontaine and ‘Born To Live’ by Marianne Faithfull. What is the process in scoring your films?

NEF: It depends. In Bedwin Hacker (also distributed in the US) I called a French friend, Milton Edouard, who is a composer. He came during the film shoot and also plays a role in the film, and he was working on the music during the production. For Ouled Lénine and Laïcité, Inch’Allah! the songs are part of the story, they are a form of commentary; in general I look for them during the editing. For Capitale Parenthèse they were recorded during lockdown and I decided where to place them during the editing. It must be said that for this film I forced myself to use only the images and sounds recorded during this period. I listen to music all the time, of any style and from any country. My tastes are very diverse.

Q: Capitale Parenthèse was presented at the 33rd JCC Carthage Film Festival and you were a jury member there, what was it like to be able to return to Tunisia after the ostracism you’ve gone through with your previous works?

NEF: I have been living in Paris for 20 years now, I had left Tunisia in September 2001. During the revolution I wanted to return to settle myself there, because I consider it to be my country. Now I go back there once or twice per year. Since the end of 2017 it is no longer the same for me. Something was broken, apart from some very dear friends and my family, I don’t feel like living in my country anymore. I didn’t receive any solidarity from fellow filmmakers at the time. Young people barely know my story; they don’t watch my films because no one has shown them for 10 years. At the last JCC Carthage Film Festival, in the printed catalogue they put the synopsis of another film for my Capitale Parenthèse. It was only screened once, in a screening room where there was a poor quality of sound and image. I was a little bitter. However, the films I want to make always concern Tunisia.

Q: During the festival you openly expressed on stage your solidarity towards Iranian women and even wore a T-shirt to support the movement that demands the freedom of filmmaker Issam Bouguerra. How do you feel the kermesse, and Tunisian people are responding to these calls for actions today?

NEF: I very much appreciated the very positive reaction of the public when I made my statement that was shared by an online media outlet. I would have liked people to talk about my film as well, that was not the case. No Tunisian journalist thought it worthwhile for me to be invited as a member of the Official Documentary Jury, even though it seemed to have been the subject of an upheaval. When Férid Boughedir made a book that retraced the history of Tunisian cinema, he didn’t mention me anywhere. I find it reprehensible to want to erase me from Tunisian cinema in this way, that’s why I allowed myself to be noticed otherwise.

Q: What is your next film about and when will it be ready?

NEF: I don’t know yet when it will be ready. It’s called Tunis Forever. It’s an acerbic comedy. This is the pitch: “To divorce the father of her daughter in order to marry her Cuban companion, Elyssa returns to Tunis after twenty years of absence. She suddenly dies. Chams, her daughter, prevents the religious burial. Her death like her life shakes up the identity codes of a society frozen by respect for traditions… Although…”