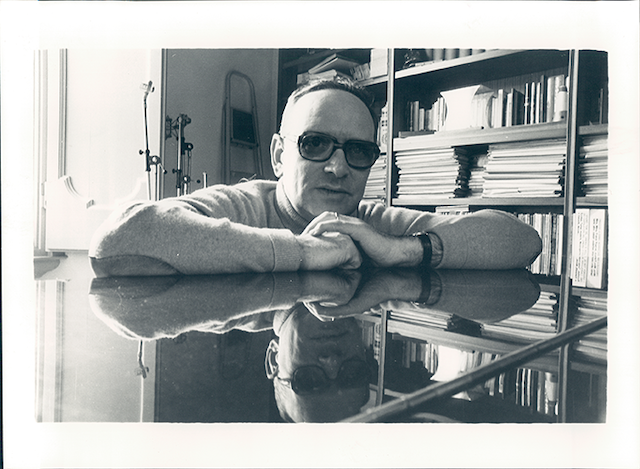

©Ennio Morricone in Ennio. Courtesy of Music Box Films.

Synopsis : A feature documentary directed by Giuseppe Tornatore about the life and work of legendary composer, Ennio Morricone, including interviews with renowned filmmakers and musicians, recordings from Morricone’s acclaimed world concert tours, clips of classic films scored by Morricone and exclusive footage of scenes and places that have made up Morricone’s life.

Genre: Biography, Documentary, Music

Original Language: English

Director: Giuseppe Tornatore

Producer: Gianni Russo, Gabriele Costa, Peter De Maegd, San Fu Maltha, Kar-Wai Wong

Writer: Giuseppe Tornatore

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Runtime:

Distributor: Music Box Films

©Giuseppe Tornatore in Ennio. Courtesy of Music Box Films.

Exclusive Interview with Director Giuseppe Tornatore

Q: You and Ennio Morricone knew each other ever since “Cinema Paradiso”. What was a significant reason that you had such a long lasting relationship?

Giuseppe Tornatore: We worked and spent time together for 32 years. From the very beginning of our collaboration with “Cinema Paradiso,” I always entrusted the music of my films to Ennio Morricone. From the start, we had a very beautiful professional and human relationship. We understood each other and it was very easy for us to become friends not only on the set but outside of work as well.

Whenever I had the idea of doing a film immediately, instinctively he was the person that would come to mind as the composer. When he knew of this film even before knowing whether or not it would be made, he would already have certain ideas in his head for the music. There was a great affinity between us that led to our relationship lasting until the end.

Q: Talk about Ennio’s formative years, particularly his relationship with his father especially when it came to a work ethic. His father taught him to play trumpet.

Giuseppe Tornatore: The relationship with his father was really very fundamental to both his personal and professional life. His father transmitted a sense of music to him as an absolute necessity of life. So music was something that gave him an existential outlook, a sustenance, a way to live. To live without the trumpet, without music, was to face hunger instead.

This gave Ennio a sense of the absolute primacy of music in his life, music as a primary need. It also triggered an antibody in him from childhood on. He didn’t like this idea of music being only used for the sake of entertainment like the music you would hear in a dance hall. While he accepted the structure that his father imposed on him in playing the trumpet, he went beyond that and went to the Conservatory to study composition.

This is a pattern that he would then repeat throughout his life — every time that something was imposed upon him, he would go beyond it. He always had the last word because he was not someone who wanted to be imposed upon.

Q: When you and Morricone worked together, he didn’t suggest or talk about any of the casting. But what kind of conversation did you two have about creating such wonderful music? What conversations did you share, going back and forth to talk about creating the music? Take me through your creating process with Morricone?

Giuseppe Tornatore: We found a different path from the traditional one as to the composition of music for film — not to cast any kind of negative judgment on the traditional approach. What we liked — and I liked — in particular was to give music a role that wasn’t secondary and to not come up with a musical score once the film had already been made.

Instead, he would start thinking of music at the same time as I was writing a screenplay. When I had finished the screenplay or even while I was in the process of writing it, I would share aspects of its structure or maybe some of the secrets of the screenplay with him. He would use this to create the base of the score that he was going to write. We were working at pretty much the same pace and we met each other this way.

There was an intersection between our ideas and an exchange of experiences. For example, I might talk to him about a certain character and he would then say, “the music should be inspired by this character rather than that one “ — or he might be inspired by the structure. This [assigned] a very important role to the music. As I said, I never liked the idea of the music being composed after the film was made.

When we went into the editing room, I already had the music in my ear; it had already been composed. In a certain sense, my screenplay was already accompanied by his musical score. While I was shooting, it was already ready. This is what led to a very different kind of film I would say because of that kind of mutual dependence on each other.

©Ennio Morricone in Ennio. Courtesy of Music Box Films.

Q: Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone actually went to the same school. Some of Leone’s early work such as “A Fistful of Dollars” was a remake of an Akira Kurosawa film. Did he have some influences from the Japanese film in order to create some of the film’s composition?

Giuseppe Tornatore: I would actually exclude that idea because Ennio was not someone who looked for inspiration in pre-existing music, musical scores or even in the actual music that he did. He was very personal in his approach, he composed according to what he felt. For a film score, he had this extraordinary ability to combine this very personal approach to music for a score because he could look at a sequence in a film and immediately think of a musical score that would go with it.

There was no room in his style or approach to be inspired by other people’s music. When a producer or director would ask him to make something like Mozart or do an oriental type music or a Mexican type of sound, he hated that.

Q: Talk about Ennio’s relationship with his wife Maria who at times decided his music for him when he had too much choice.

Giuseppe Tornatore: In addition to being a really prolific composer, Ennio was extremely self-critical and didn’t often realize the importance or the excellence of what he had composed. He sometimes would compose a really beautiful theme and think it was nothing special. He needed a figure to mediate between his generosity of composition and his excessive self-criticism.

Someone who would take what he had done and make him understand the taste of the audience and how much they might appreciate what he had done. Maria was that important figure. She was a mediator between his unstoppable genius and his excessive self criticism. He wasn’t a really very good judge of himself.

He thought that what he was doing was perfectly normal and she understood, instead, the gift that he had, the quality of some of his things [he had created]. Even before showing a piece to a director, he would show it to his wife and once she had decided on it — had approved it — then he would present it to the director. He might be writing something truly extraordinary and to him, it would just be adequate. He was so self-critical that he was not the best judge of his work.

Q: Some of the experimental sounds that he used in his compositions like using a typewriting sound or making sound out of a soda can were surprising. Talk about his experimental approach on composing the score such as the whistling in “A Fistful of Dollars” and “Once Upon a Time in West.”

Giuseppe Tornatore: From the very beginning of his work as a composer, he was very drawn to musique concrete which was this incident noise of everyday life in musical composition. He was one of the first however to use musique concrete within the structure of tonal music to bring the two together.

He would use concepts and ideas from concrete music, for example, a pop song from the 1950s that we see and then he did the same thing with the scores, to the film scores. He was constantly searching for different sounds. His experimentation, his style evolved from these very realistic sounds into creating sounds that had never been heard before, the invention of sounds that didn’t exist in reality.

Even already in some of these very successful pop songs in the 1960s, we see some very experimental couplings that became very popular and imitated by many others such as the combination of the female voice with a trumpet and the male voice with the trombone, which is something that no one had ever done. It was absolutely new and then copied by many others. He was always experimenting with things that had never been done before. For him, I would say that to compose was to experiment.

©Ennio Morricone in Ennio. Courtesy of Music Box Films.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q5WBbULw_0U