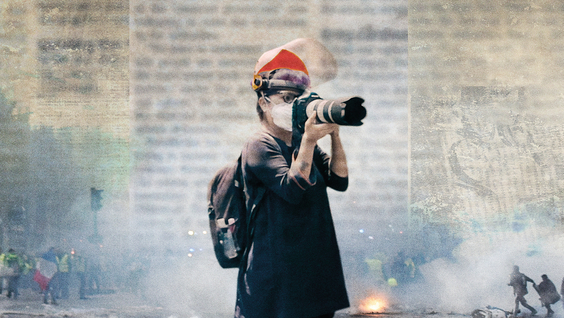

Synopsis : Endangered chronicles a year in the life of four journalists reporting inside Mexico, Brazil and the United States — three democratic nations where the view of the press is rapidly deteriorating. As newsrooms shutter around them, misinformation proliferates, and world leaders brazenly suppress free speech, Patrícia, Carl, Sáshenka and Oliver risk their sanity and safety to make sense of a world out of balance.

Exclusive interview with director Heidi Ewing

Q: In the movie, you talk about how we can’t have a healthy democracy unless there’s freedom of press. Certainly, the Trump administration made us realize that. But what were the trigger points that made you decide to make this film?

H.E: I’d been talking to co-executive producer Ronan Farrow for a while about doing something together. We were looking [at our] common interests over time. He has had some experience of being followed, and has [experienced] some harassment as a writer.

But obviously, this film is about something else. We kept coming back to this issue of journalism under threat. At the beginning, we focused on countries like Cuba, Malta and Russia and all of that. As we really started to get serious about making a film, we decided to look at our democracy, where freedom of the press is under threat.

The Trump administration reminded us about how you can direct hostility towards an entire group of people, especially if the person on top is allowing and encouraging it. So we looked around in the neighborhood of the United States and the Americas, and focused on Brazil because Bolsonaro is very similar to Trump in the way he talks about and treats the press.

We thought it was interesting to look at Mexico, because Mexico has one of the highest numbers of journalists that get murdered every year of any country in the world. We wanted to take the temperature there. We had no idea that, while we were filming, “Black Lives Matter” would take off and we would see outright harassment and violence against the American press. We did not expect that when we started. So that really reminded us of how timely this film actually was.

Q: Talk about the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York. This organization monitors and combats press freedom abuse in 120 countries around the world.

H.E: The Committee to Protect Journalists has been around for many, many years, and they focus on journalists who are in jeopardy and peril outside the United States. They didn’t focus on the United States because they’ve never had to — until now. So basically, when a journalist gets harassed, jailed, goes missing, is killed, they try to bring global attention to that missing person — or that murder or imprisonment — in order to or to investigate the crime or pressure the government holding the person to do the right thing.

Basically, they’re advocates for journalists around the world — it is the number one organization doing that. It was only during the last couple of years where they’ve gotten calls for help from American journalists living in the United States that they were asking for security training and protocols and help.

It’s a great organization, and we spoke with them at the beginning of the production to get some other ideas about where to look. They’re the organization that introduced us to Patrícia Campos Mello in Brazil, because they had given her this award [due to] her courage when it comes to reporting, especially on sensitive political issues, and when it comes to Jair Bolsonaro.

Q: In the film one of the reporters mentioned taking the course on how to stay safe in a conflict zone. I think all major outlets should offer those courses to teach journalists who are assigned to go into conflict zones. Do they have that system in outlets in the U.S.?

H.E: No. Journalist security is not a strong suit of American networks or, I would say, of any network around the world. That is why the Committee to Protect Journalists needs to exist. I know Reuters does have some training classes.

I think in the scene in the movie you are referring to, she is talking about Reuters.

I really think that they do their best, but all these organizations are understaffed, underfunded and overly busy. I don’t think that they have the resources to focus on this. So a lot of times, the journalist pays for her own transportation, security and helmet. Cameras get stolen and smashed, and there’s very little help available to most journalists around the world.

Q: Ever since reporting the Harvey Weinstein incident, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize, Ronan Farrow has been one of the foremost investigative journalists. Talk about his involvement in the film.

HE: Ronan is a very important mouthpiece, figurehead and recognizable personality. There are few young journalists recognized worldwide, or at least in the United States. Ronan has a really big following, and of course, has been instrumental in breaking open the Harvey Weinstein/#MeToo story.

He’s always been a really vocal advocate for a free press and the right of the press to ask whatever questions they want to ask as long as they’re staying within the rules of journalism. I think by getting out in front of the film, promoting it and talking about these issues, he will really help get the message out as far and as wide as possible.

Q: The Miami Herald filed for bankruptcy, then was bought by the Chatham Asset Management hedge fund. To cut costs, the paper continues without a newsroom — because of COVID, the growing wave of digital media, and owners who have no newspaper experience.

H.E: There’s very little money available, they don’t have the resources, the transportation. Its journalists don’t have the money to fly around to do stories. The Miami Herald used to send journalists all over the world — Haiti and all over the Americas. Miami is an international city so there were international stories of interest to their readership.

The budgets have gotten cut down to where Carl Hiaasen is just doing everything on his own: he shoots the video for the paper, he photographs — you see him running around the streets trying to upload photographs to his editor. People have become one-man bands. They’ve become lone wolves where they used to be a team.

It’s bad for morale, and I think journalists are spread far too thin. We would like to use this film to bring in more young, energetic and excited people to inspire others to join this profession. It’s so, so crucial to have young minds entering the field. Our dream is to start something called “The Reporter Corps” where there’s actual money to train young journalists who are interested in joining the profession.

Q: It was scary to see what American journalists went through covering the last election, how the whole country was so divided that some voters refused to listen to opponents. In shooting this film, when did you realize how strong that division was?

H.E: There’s one thing to know intellectually about the polarization in the United States. It’s another thing to be out there with a reporter or on your own, and to be treated with suspicion, derision, and hate, just for asking questions that might seem like a point of view that’s not the same as yours. So, to be standing next to these journalists while they were undergoing this sort of harassment is jangling to the nerves. You feel it in your body, and, as you see in the film, the physical posture of the journalist even changes while they’re trying to do their job. They don’t know what’s going to come at them next. Especially with Oliver Laughland from The Guardian. It was extremely discombobulating and disturbing to actually experience it as opposed to just hearing or reading about it.

Q: In shooting this film, did your thinking about freedom of speech change? There are so many different aspects of it that you talk about in this film.

H.E: Social media has changed the whole conversation. Allowing everybody to say whatever he or she wants, especially when it’s information that could hurt somebody, like we saw a lot with Covid. I don’t think it should be a free-for-all.

People can be allowed to have their opinions as long as it’s clear that it’s their opinion and it’s fine. But when it comes to hate speech, harassment — when it’s misinformation that can cause bodily harm to somebody — I think we have to make some decisions as a society, and have to draw the line.

Because we see that speech can turn into action. We see that you can incite a crowd to violence that otherwise would not have engaged in violence. Words matter. We can’t pretend like it’s just air. Words translate into action — we see it over and over and over again.

I disagree with Elon Musk that you should just let Twitter be a free-for-all. I don’t think society is ready for that. You can’t censor someone just because you don’t agree with their opinion. But in cases where you could cause damage — and I think we know where those lines are in our society — that has to be looked at. The Right loves to accuse the Left of censorship. But I think we’re just talking about common sense.

Q: What do you want audiences to take away from this film?

H.E: I think most democracies — definitely in the United States — have taken freedom of the press for granted. We never thought about it, it’s in the Constitution. It’s something the United States has boasted about for years with a lot of pride — that we have a free, robust press that can operate unhindered and do their job.

Well, that’s no longer a given anymore. We can’t take it for granted. We talk about preserving our democracy, fighting for democracy. We have to start rolling in these issues of freedom of the press. We can’t leave it over there. It’s part and parcel of a democracy, and I think Americans haven’t paid attention to it. Hopefully, this film will remind them that it’s also on the chopping block if we do nothing about it.

The press is very inconvenient to the powerful. The press is inconvenient to the Right and to the Left, because they’re digging up stories and trying to hold the powerful accountable. So if the people don’t care about a free press, I’m telling you, the government does and I include both the Right and the Left.

Most Senators and Representatives see a member of the press coming their way and they run away. They run — it doesn’t matter what party you’re from. So I think the people have to care about the issue. Otherwise these freedoms will be more and more denigrated and degraded.