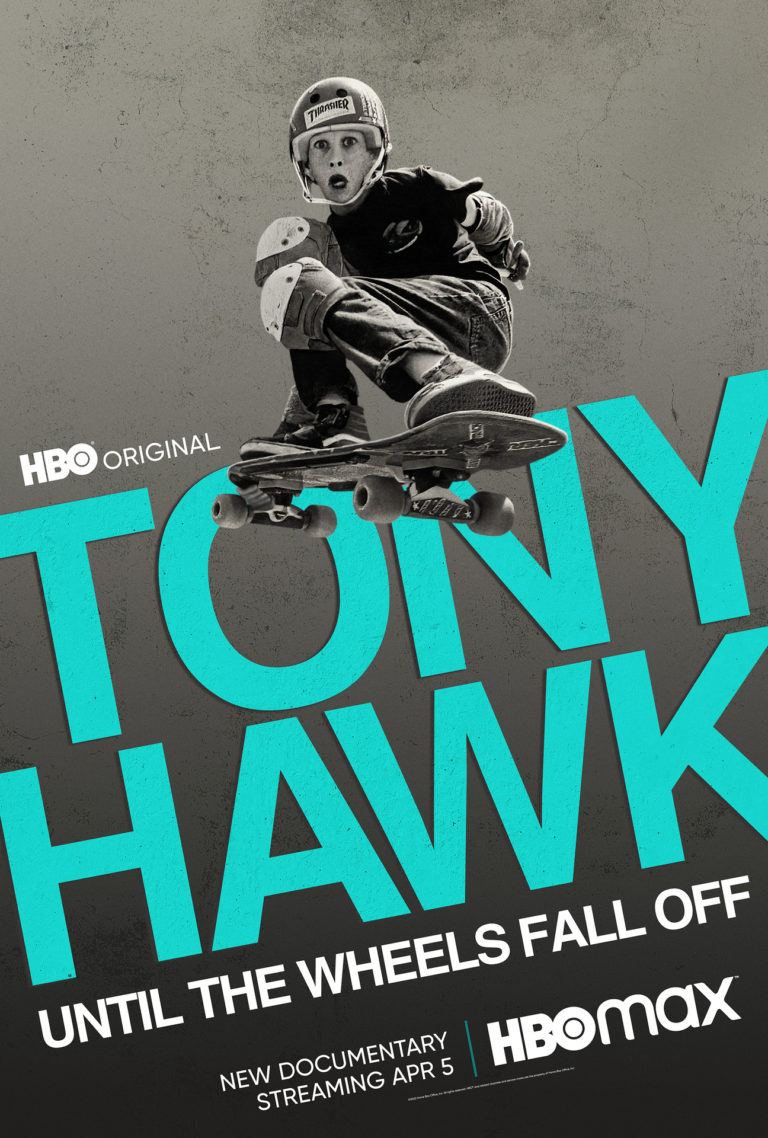

Synopsis : Centering around intimate new interviews with Tony Hawk himself, the film is an all-encompassing look at the skateboarder’s life, legendary career, and relationship with the sport with which he’s been synonymous for decades. Hawk, a pioneer of modern vertical skating who is still pushing his limits at the age of 53, remains one of the most influential skateboarders of all time.

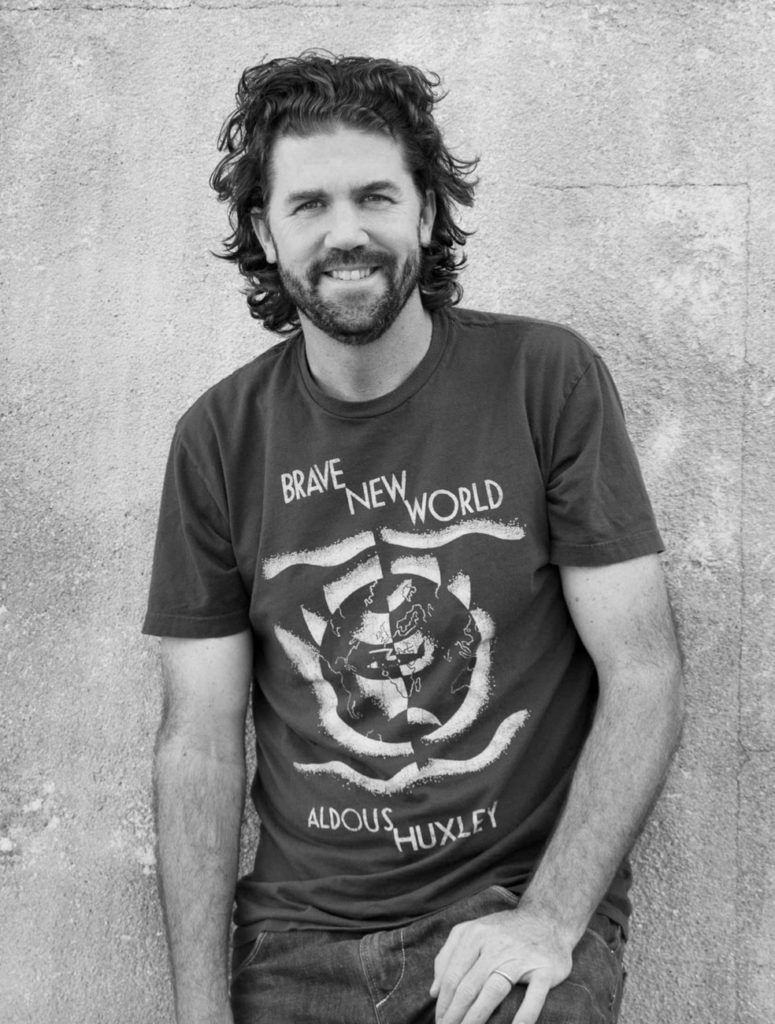

An Exclusive Interview with Director Sam Jones

Q: So Sam, what’s your relationship to the skateboarding world? How did you get to know Tony Hawk?

SJ: I’ve been a skateboarder since I was eight years old. I saw Tony at the skate park in 1983, probably for the first time. I was an amateur competitor, I was sponsored by a local skate shop, and it was my life for many, many years and I still skate to this day. So skateboarding has been a huge part of my life since the beginning.

Q: How much do you think it was significant for Tony to meet Stacy Peralta, who founded the Bones Brigade and took Tony under his wing, in a way. So Stacy Peralta also made a skateboarding video when nobody considered skateboarding as a sport. It must be a significant meeting; it launched his career, in a way.

SJ: Very much so. The fact that Tony met Stacy is one of the great collaborations. You think about other collaborations like that, like Michael Jordan’s first coach at North Carolina. I think with Tony and Stacy, it was very fortuitous for Tony because Stacy had been there and Stacy was a young phenom that the media grabbed onto in the first wave of skateboarding.

So Stacy understood what Tony was going through, and Stacy could also see that Tony had qualities and other people couldn’t see them like Stacy could. Stacy could see that the mental game was there with Tony, and his grit and his determination were there. Stacy had an incredible ability to nurture talent in the way that each individual needed it. So the two of them meeting was hugely important for Tony’s career.

Q: I didn’t know that Tony wanted to quit skateboarding at one point. There was a point that he was singularly focused on competition, which is, in a way, like a machine to him, sort of like sucking fun out of it. His father was also the founder of the NSA, which is the National Skateboarding Association. So every time Tony won the competition, people thought that was the father pulling strings or something like that. I’m curious about how difficult it was for him to maintain as a kid, but still have to compete, back then.

SJ: Yeah, before video, the way that you got in the magazine was you won a contest or you placed high in a contest, and that made sponsors want to give you equipment and have you ride for their company. So it was all based around competition in the early eighties. The judging was still being figured out. The system for judging that we use now today in skateboarding, it was being figured out then.

A head-to-head format, scoring based on tricks, but also on the sort of factors that, interestingly enough, if you were a skater and you pulled off a trick but you almost fell, that would score you higher than if you pulled off a trick and made it look easy. And Tony had some troubles with that because he was so good and so consistent that he would win a contest and if another skater sort of almost reached Tony’s level or stayed on or had a run that looked kind of out of control and made it, they would be rewarded for that.

So Tony ended up competing against himself because the judges would say, “Well, last week Tony did these ten tricks, so today he has to do eleven tricks.” Whereas other skaters could only do five of those tricks.

So in its early days, it was a lot about competition and I think that what Tony found out was, when you are so much better than everybody else, or when you are doing tricks that no one else is doing, the system has to catch up with your ability as an athlete. The system had to catch up with Tony Hawk and it got demoralizing for Tony. There was no enjoyment for him for awhile.

And then video came along, and you could do tricks and make them, and people could see your progression and people could see your artistry and your creativity. So the skate industry shifted away from competition and more towards the visual aspect of skating. So you had this new generation of skaters that got sponsorships and money and careers because of their style of skating, but not just because of their competitive record.

Q: As much as Tony could get criticized by people because his father founded NSA, at the same time, without his father, we wouldn’t know that Tony was skateboarding or became the Tony Hawk he is now.

SJ: That’s right.

Q: You described the relationship with his father as very special for him to be successful and at the same time keep a distance at some point when they are competing. It was quite a tricky situation, I imagine.

SJ: It was. And if you think back to the time that Tony was coming up, his father was in World War II and men weren’t noted back then for their emotional connections and communication skills. But Tony’s father had a really rough upbringing and was not close to his father. So I think that even though Frank Hawk did not have an emotional language, or an ability to communicate emotionally with his son, and maybe did not have the greatest skills in a marriage to communicate with his wife, he did understand how to show his love by putting in the time in supporting his kids.

I think Frank’s legacy is that he wanted to make his kids’ childhood better than his own. So Frank, rather than pursuing his own ambition after he got out of the Navy, decided to devote his life to his kids. When you are an adolescent and your father is at all of your competitions, and you’re trying to fit in with the crowd of kids, the last thing you want is to have your parents there. And that was a complicated thing for Tony, because he loved his father.

Tony’s a very smart guy, and he understood how valuable having his father there was; but at the same time, it made it incredibly hard for Tony to form social bonds with kids of his own age. So it was a tricky situation.

As a kid, you see a parent as an authority figure. But as an adult, making this film and watching all of this footage, my heart kindof breaks for Frank Hawk because he was willing to take so much of a beating from all the kids in order to be around his son and spend time with his son. It was a noble thing, and he didn’t have the language to express his love. And I really wanted to tell that story in the film, I really wanted to show the complexities of that relationship.

Q: You truly did a great job on that. X Games in 1999, Tony must have tried probably dozens of times for the “900”. How did he maintain his mind through the physical. So how did that achievement make the skateboarding industry different after that? But he went to another level, on that day!

SJ: Yeah. A lot of factors came together on that. Ninety-nine is when SportsCenter was at its peak, and it was really watched as a show. And before the internet really took hold, that was the place where you got all of your sports information. They were at the height of their popularity with the commercials they were doing. The X Games had been around for four years at that point, and every year ESPN had seen growth.

So when Tony lands that “900” he lands it in such a spectacular way, because he wasn’t going to quit until he landed it. So the competition had ended, but ESPN just kept broadcasting because everybody that was there at the competition wanted to see if he could land this trick. It’s almost like you can’t look away. There’s somebody that’s just throwing himself up in the air, and it became this great television moment. And when he lands it, that clip must have played a thousand times on SportsCenter over the next few weeks or a month.

It was the first time that people who are golfers or basketball fans or baseball fans, or mainstream stick-and-ball sports – it was the first time that they had this image replayed and replayed to them through their mainstream communication device of this skateboarder. And in a way, it was sortof like you had to dumb it down for the mainstream. He did two and a half spins, and people who don’t even understand skateboarding could see how hard a trick that was to pull off.

So that became this moment that I think legitimized skateboarding right then as a sport that people understood the difficulty of, through watching Tony Hawk, and he became the ambassador of the sport overnight to the mainstream audience. If people were going to remember any name, they were going to remember his name.

Q: I didn’t know that Tony had a bunch of odd jobs in the early 1990s, because I initially saw that once he turned pro, his career took off and he has always been successful. But I didn’t know he had odd jobs in the early 1990’s trying to make ends meet, and still trying to stay involved in the skateboarding world as a sport.

SJ: Yeah, skateboarding had to go through a transformation. In the film, Stacy talks about it being cyclical. But my take on it is that skateboarding had to transition out of the period when there were these skate parks built by first-generation hustlers and entrepreneurs that didn’t know how to build good skate parks.

So kids weren’t having that great an experience in the late eighties with the terrain that was available, and out of frustration kids took to the streets. And so when the kids took to the streets, and made it their own pursuit that didn’t require wearing pads or getting a membership card, or having your parents drive you to the skate park, that transformation had to occur.

And a lot of companies went away from skateboarding, and vertical skateboarding went away for a period of time. Suffering through that dip in the early nineties, skateboarding had to learn what it was going to be to have its next rise. The X Games is part of that, Tony was obviously a big part of that, and the street skating – the level of difficulty and the tricks in street skating went up. And then I think that made kids appreciate vert skating again.

Because there was the time when kids just didn’t appreciate vertical skateboarding. They just wanted to see handrails, and they wanted to see ledges, and giant gaps and things like that. So it took Tony and the X Games to bring an appreciation back to vertical skateboarding, and then we had the second wave of skate parks.

During that time, yeah, Tony was a kid making a bunch of money. But once the contest earnings and the board sales dried up, he found himself just another person with a couple mortgages and a child, and a marriage that was falling apart, and there was no income.

Q: I want to ask about the Animal Chin video, they got together all the skateboarding people, but Tony had a bad concussion on that day. But even with Stacy Peralta asking him maybe it’s time to quit, but he’s still going on. But what is the motivation that he’s still trying? It’s so amazing that he is still doing it.

SJ: Well, I think Tony is very aware of his own parameters and limitations. The technical part of that question is that the animal chin ramp was built to the specs of the old animal chin ramp, when skaters had tighter transitions.

Back then, we had eight or nine transitions from flat to vertical, from flat to vertical. It’s a nine-foot radius or an eight-foot radius. Now, ramps are eleven or twelve-foot radius. So there’s a lot more room to fall without hitting the bottom so hard. If you think about surfing, surfing a small wave requires a very different approach than surfing a big wave. And it’s the same thing with ramps. If you’re used to riding this massive transition and then you go to a ramp that has a smaller one, your body has not had to adapt to that size of transition for a long time.

So I think from the outset, it looked like Tony was really being very risky, but the truth is he was just used to a different size ramp, and he miscalculated on that day. But I think in a way it was a very helpful slam for him because it made him realize – it was another piece in the puzzle of how to keep doing this in a way that he could do it on his own terms.

But it is a very scary moment in the film, and it brings up a whole argument and conversation about how long we can continue to do these kinds of things as we get older. And who defines that?

Q: Thank you so much.