©Drafthouse Films

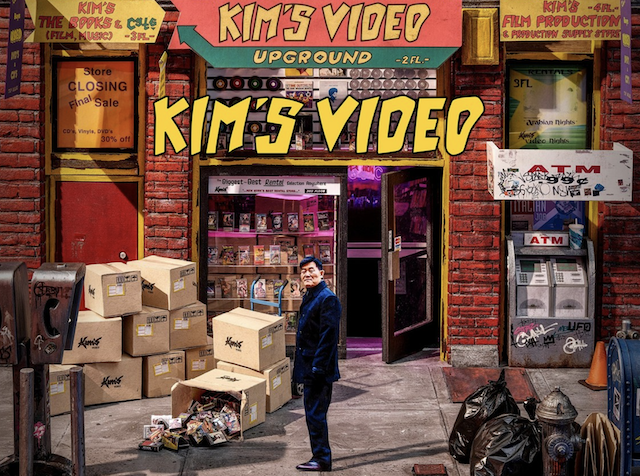

Kim’s Video : Physical media reigns supreme in KIM’S VIDEO, an elegiac tribute to the iconic video store in New York City that inspired a generation of cinephiles before it mysteriously closed its doors and sent its legendary film archive to a small and slightly dubious Sicilian village for “safekeeping.” But what starts as an homage to cinema quickly becomes a rescue mission to ensure the eternal preservation of the beloved video collection.

Genre: Documentary

Original Language: English

Director: David Redmon, Ashley Sabin

Writer: David Redmon, Ahsley Sabin

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Runtime:

Distributor: Drafthouse Films

Production Co: Carnivalesque Films

©Drafthouse Films

©Drafthouse Films

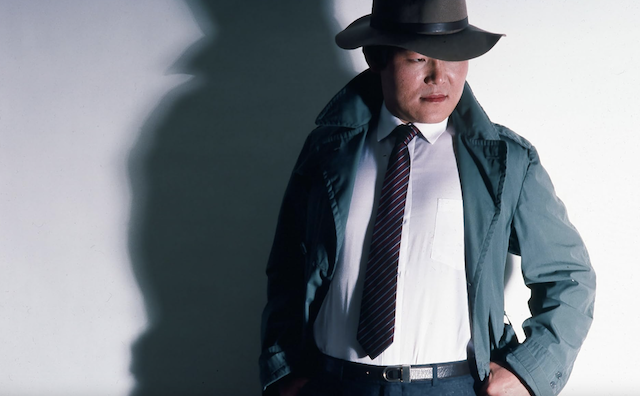

Exclusive Interview with Yongman Kim, a former owner of Kim’s Video

Q: Mr. Kim, you grew up in the early ‘60s in Gangnam, South Korea, on the outskirts of an airbase there. What was your initial interest in the film industry back then? How did you get interested in the film business back then?

Yongman Kim: I guess everyone has a dream about the movie. So did I. There’s a huge American Air Force base in Kunsan, Korea. I grew up with a lot of military officers and US GIs. Luckily, when I was eight, I had a very old version of a Charlie Chaplin film to watch. My curiosity really stems from that age. I very much thank my hometown of Gunsan which allowed me [to discover] a lot of American culture including not only the film, but also music and magazines. I actually grew up with strong American cultural influences.

Q: What was your concept of Kim’s Video? It’s similar to the impact that you had when you first arrived in the US, exposed to all those films back then.

Yongman Kim: I have two things. I happened to settle in a place called the East Village. The East Village in New York, Manhattan. Back in 1980, it seemed to be pretty chaotic because you see a lot of things that really weren’t pretty. That included a lot, maybe 5,000, homeless people there. Also, the headquarters of many drug dealers and a lot of prostitutes; every evening they were on the streets.

It was a really chaotic situation. But to me, two of the young men from Korea just arrived in the US. That looks to me that instead of looking chaotic, then look to me, that’s the wde free country in the US. I ended up meeting a lot of friends, basically, most of the friends had an art background and that included music and film as well. A majority of my friends also came from Eastern Europe; a lot of European citizens ended up in the East Village. I met a lot of poor young artists there. All those things really affected me, and actually reminded me about the passion for film that I had from age eight.

Q; In the film, you went to many festivals around the world to get in touch with some of the distributors and filmmakers to acquire some of the films for your stores. What were the parameters, what sort of films were you looking for back then? Were there specific types of films that piqued your interest?

Yongman Kim: Of course. I started my first video store as part of the dry cleaner. Assuming that the space was pretty limited. I didn’t want to fill all those shelves with Hollywood junk. I made it very clear from the beginning that all this film must be pretty selective. it should be something pretty different than every other video store. And that was my direction. We started with 1700 films at the beginning, adding only select new videos, focusing on foreign films and more cult films and independent and underground films. From the beginning, I had these pretty strong principles and then continued from there. As Kim’s Video grew , the catalog — our collections — also grew in the same way.

Q: There’ve been many filmmakers and industry folks who had worked in Kim’s Video such as directors Robert Greene, Alex Ross Perry and Tom Phillips — and Eric Hynes, who is the lead curator at the Museum of the Moving Image. How did you come to hire those people? Did you interview them? How do you approach young people who are interested in working at Kim’s Video?

Yongman Kim: I directly conducted interviews with anybody from an assistant manager to manager level on. The clerks and regular staff were hired by the managers. At that time in Manhattan’s East Village, there were plenty of people pretty knowledgeable about all types of film and music as well. I was very thankful that all that manpower was always available there. All the people you named were part of that group of very talented people that I luckily hired.

©Drafthouse Films

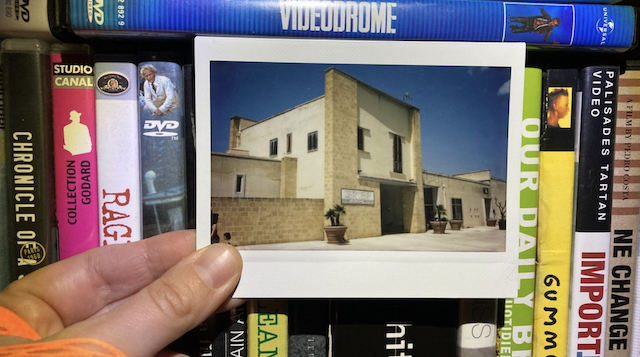

Q: Obviously, after the earthquake in Salemi, the city needed to rebuild and develop some attractions. But why did you end up choosing Salemi instead of placing the collection in New York University’s library or other local organization or location?

Yongman Kim: I don’t know if you’re up to date about what happened with the Kim’s Video collection when I closed Mondo Kim’s. This is the story. I had opened 11 locations of Kim’s videos. Every time I closed one, each location’s collection was always donated to colleges.

I donated here and there to some institutions like Columbia University. We donated 45,000 titles. I donated 35,000 to Ramapo College of New Jersey. Here and there, we donated over 300,000 videos and DVDs. When the time came to close the Mondo Kim’s store, that location had the biggest catalog, which was about 55,000. Those collections were really my baby. The collection was really awesome and everybody praised how lovely it was and how they enjoyed it. I had the same feeling.

I put an advertisement in the Village Voice with three conditions. I will donate it as I did with the tapes and DVDs from my other locations. Anybody who will take on these three conditions, then I will donate it. The three conditions were: first, a minimum three thousand square feet were necessary for the physical location and must be set aside. Number two, a trained staff needs to be hired to update and manage the collection. And finally, my collection must be available to the public; there should be access to those who wished to rent a movie.

Within two weeks, I got about 40 to 50 institutions interested including the most schools around New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Long Island and Pennsylvania. They all applied for it. As I was negotiating, most institutions had a problem with the third condition, which was that public access should be permitted. They wanted to negotiate about that condition, which I couldn’t accept. I declined, rejected and denied most of the institutions’ offers. While I was doing the negotiations, surprisingly, one of the students who came from Sicily contacted his hometown — this is in the movie. They contacted me and said they would accept all of my conditions.

They wanted to accommodate me to bring my collection to Sicily. It sounds very weird, but to me, it really made good sense, because I would give them a great video collection from the New York area that a lot of institutions had wanted and they had this great plan to bring my collection to Europe. Vittorio Sgarbi and Oliverio Toscani, two very famous Italian cultural icons, were to be involved. Once I checked out their background, it made good sense. They could maximize the use of my collection and Europeans could use it for their film passions. That could be a good platform to attract a lot of young artists, as it did for me in 1985 in the East Village.

Q: That’s so true.

Yongman Kim: At the same time, Sgarbi offered a beautiful home to house the collection. I checked many other houses available in the area. Though it was abandoned, the house was still very beautiful and ancient — it could have been a thousand years old — but it was still in very good shape. So, with the day of the program and my collection, I expected it to be something that would do very well there. That’s the reason why I decided to send the collection over to Sicily.

Q: Considering your aspirations to be in the film industry, you made a film, “One-Third” as a director/producer and you also produce some films like “301, 302” and “Farewell, My Darling.” Are you still continuing in that direction? Do you have any projects that you’re working on or are you totally separate from the film industry right now?

Yongman Kim: I can’t explain it, but throughout my life, I can’t live without film. It’s a part of my brain and body. I can’t stay away from it. However, I’ve always had priorities. As I get older, I have to be more realistic. Yes, I’ve had a trilogy film project that I’ve wanted to make. There was a reason why I called it “One-Third.” That’s the base, but I wish I had the script for “Two-Thirds” and “Three-Thirds.”

I still want to make films, but as you know, making films is no joke. It takes a lot of effort and sweat to be invested into it and a lot of collaboration is required and so forth. I’ve been waiting and waiting — and all of a sudden, more than 10 years have already passed. So, my passions are still in it but realistically, I need more resources to put into it to make things happen. My answer is, yes, I still have my heart in it, but I’m also looking for more practical timing.

Q: How did you strike the deal with Alamo Drafthouse founder Tim League to allow your collection to be showcased there?

Yongman Kim: When directors David Redmon and Ashley Sabin approached me about the documentary, there were about four or five other offers and proposals out there but I turned them all down. I wasn’t interested in them. But with David and Ashley, they already had a lot of footage from working on the story of Kim’s Video for about three years without my permission.

I was very inspired and impressed considering what they had to work with from the start. I agreed to work with them on the project, under the condition that they find a good, realistic shelter in the US for my collection. We continued our search anew, sticking to my three original conditions without alteration. It was tough going but eventually David got through to Alamo Drafthouse owner Tim League and after that, everything went very smoothly. That’s how Kim’s Video collection returned to the USA and to Manhattan’s Alamo Drafthouse.

If you liked the article, share your thoughts on the comment below.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.

Great interview with the legend! But a month into the films premier Sony bought Alamo Drafthouse. What’s the next fate going to be for this precarious collection?

NY doesn’t seem the same as when Kims Video existed, maybe one of these retro rental places in Los Angeles can get it.

I don’t see any social media about the Alamo location besides. And the few I did see were not really film people. Just clout farmers. NY has lost the indie vibe. Sony won’t deal with a basement of copied films. It’s a cliffhanger!