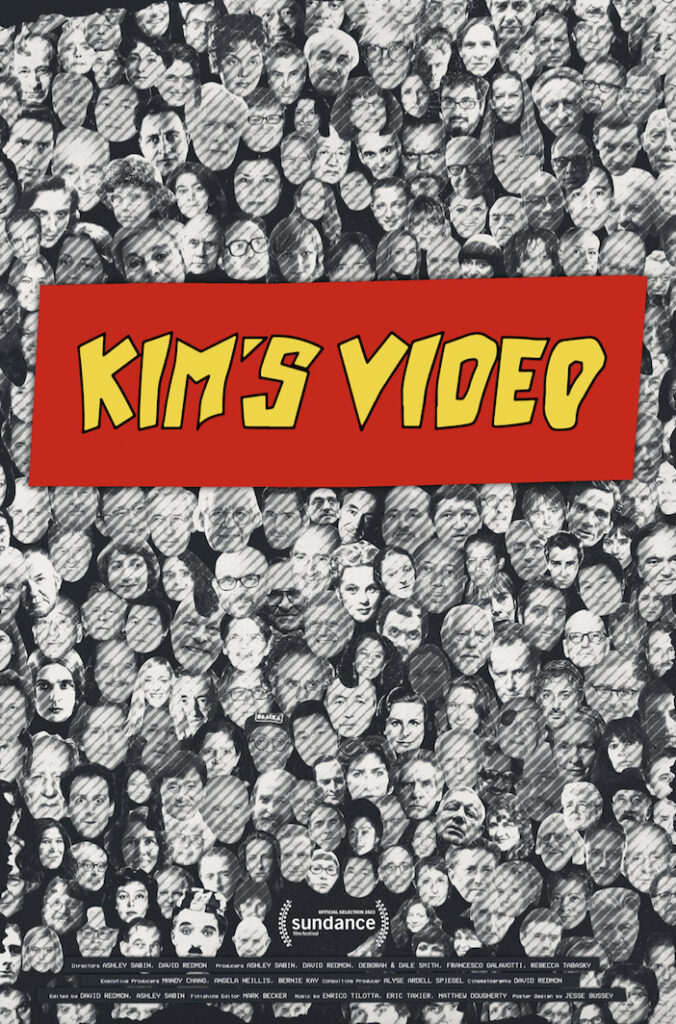

Synopsis : With the ghosts of cinema past leading his way, cinephile and filmmaker David Redmon sets off on a seemingly quixotic quest to find a legendary lost video collection of 55,000 movies in Sicily.

Genre: Documentary

Original Language: English

Director: David Redmon, Ashely Sabin

Writer: David Redmon, Ashely Sabin

Runtime:

Exclusive Interview with Co-Director David Redmon

Q: What was your experience with Kim’s Video, and how did that experience lead to making this film in the first place?

DR: It was my foundation and it held me together. It was with myself and my girlfriend at the time, Ashley Sabin — we’re married now — so every chance we got, we’d go to Kim’s Video from Brooklyn. We would bike across the Brooklyn Bridge, rent movies, take them home, watch, wake up, edit, bring it back, and do more. What’s important about it for us was the physicality. It’s a physical place to meet people, encounter movies that we had never heard of, come across movies by accident — along with other people. And that’s very important for those kinds of encounters to occur.

Q: How did that lead to making this film?

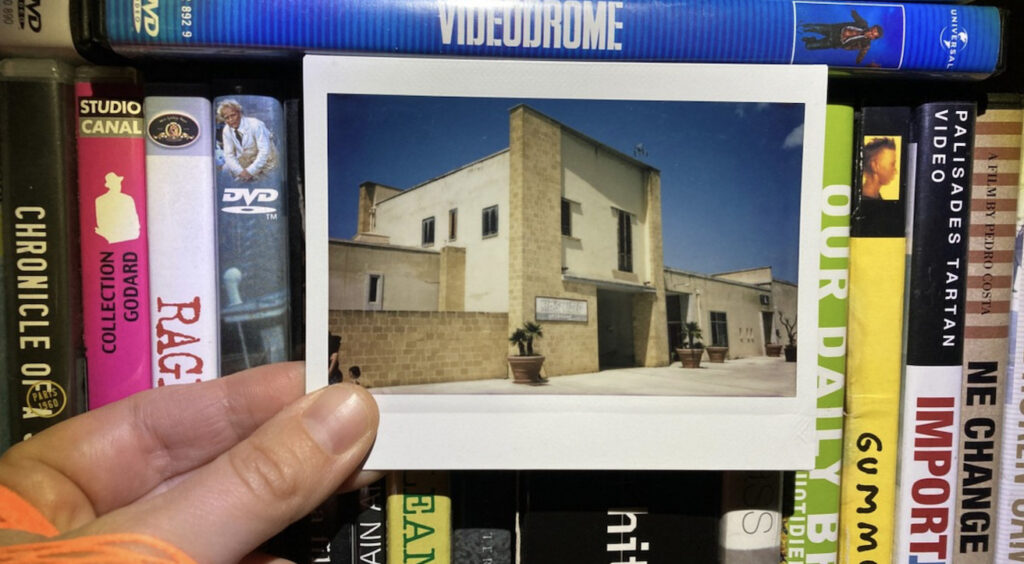

DR: When we found out the collection was leaving, we were in Russia, in Siberia, making another movie. I told Ashley,”I can’t believe it. Kim’s Video is going to be gone. It’s leaving. We have to go back to America, to New York and do this.” But we couldn’t — we had to finish our other project. Then years went by, and as the movie indicates, I started having these voices and obsessions — dreams about Kim’s Video, so many dreams. Finally, my wife, Ashley, said “Just go. Go find out what’s happening with Kim’s.” You see in the movie, I go. But I didn’t go with a smartphone, I went with a dumb phone — a little phone on which you can call or text and that’s it. No map, no direction, just went to Sicily, went to Salemi. I had to find the collection. I went to so many different places that aren’t in the movie. Finally, one man helped me and you see that man in the movie.

Q: I was surprised that directors Like Todd Phillips, Alex Ross Perry and Robert Greene used to work there at Kim’s video. I also see Eric Hynes who is a director at the Museum of Moving Image now. How did you gather those guys who used to work there, get in touch with them and interview like that?

DR: it was very difficult to gather them together and assemble so many people because most people said, “no” or didn’t respond. You have to go through agents, like for Chloe Sevigny. It was so difficult — exchanging emails for over a year in trying to get an interview. Trying to get an interview with Martin Scorsese is impossible — we couldn’t get past the gatekeepers. We sent several emails to Todd Phillips, no response. We met people around the world who were members of Kim’s Video, and they had fabulous stories. For example, a man in Sweden was a member, and his dad would fly him in as a boy to New York and they would rent movies.

He would bring them back, copy them on VHS and distribute them in Sweden and then bring them back into New York City. He now owns Nonstop Media in Sweden, one of the biggest distribution companies. You mentioned these other people’s names like Robert Greene and Alex Ross Perry. You can see how Kim’s Videos’ influence goes beyond borders. It becomes, in Robert Greene’s words, “an incubator” to help inspire and imagine what’s possible through all these collections of movies, and with the conversations that occurred at Kim’s Video. It was like a magnet that attracted them — even David Bowie was a member as well. There’s so many people — Iggy Pop, right? We chased down Iggy Pop and tried to get him to do an interview, just to speak about the influence that these movies have on anyone’s artistic vision.

Q: Youngman Kim, owner of Kim’s Video, used to send his staff members to some festivals around the world to select films for their library and collection. They went to such an extent to search out a really good movie or to find their types of films. Were you surprised?

DR: I was indeed surprised. I wish Mr. Kim was here to speak about that because he’s the one who arranged it. He explained to me that he would have six people on staff that would go to diverse film festivals — everywhere from Canada to Korea. Mostly his favorites were in Eastern Europe, he said. They would bring back these movies. Not only would they copy them from the embassy, and bootleg them — as you saw in the movie — and then the police would come and take them. He would do it again one week later. It was his vision, his obsession, and his organizational skills. Only Mr. Kim, I think, can speak to the motivation of why he did that.

Q: That’s really a smart way to acquire a connoisseur’s taste in collections.

DR: He would refer to the movie collection as his children. He opened various Kim’s Video [stores] on the date of his child’s birthday. eEvery Kim’s was opened based on the child’s birthday. So he’d refer to his movies — and I regret I didn’t put this in the movie — they’re like his “babies.” He doesn’t have a favorite, they’re all his babies.

Q: What’s surprising about the collection is that they had Stanley Kubrick’s earliest work, such as “Day of the Fight” and “Fear and Desire.” They really had a rare collection of movies. What were the films that you found or bought at Kim’s Video that were surprising that they were there in the first place?

DR: Well, Stanley Kubrick is one of Mr. Kim’s favorite filmmakers, so this is one reason why he had various shorts and different movies by him and about him. But gosh, that’s a good question. I can’t give one name. I mean, there’s Hungarian cinema — for sure, “Viridiana” — but Criterion: Bunuel… they released that on Criterion. We watched it on VHS from Kim’s. I hate to sound so myopic, but I really liked “Dogma 95” — he had a lot of vogue movies out there. I liked Harmony Korine, the immaturity, but the unknown vision that he was creating at the time.

Q: In June 2005, the FBI raided Mondo Kim’s store alleging they were selling bootlegs. They closed the store for a certain length of time, but they were able to open the stores afterwards. How were they able to manage that with the police after them? They were able to stay open for a couple of years before they finally closed permanently.

DR: That’s a good question. It’s unfortunate that I’m such a box, I want to respond in a legal manner. So once the search warrant is over, the police have to get another one. It takes months to do that. They can’t just walk in and shut it down again. They have to go through the whole process again — and again and again. But Mr. Kim had a VHS player, a VCR, upstairs, multiple. He would just copy, copy, put them back on the shelf again. But he said he was determined to make these movies available to the public. That was his motivation to break the law, to avoid the law or ignore it. He wanted to get them on the shelves and make people have access to them. This is why his condition in Sicily was to “Make the movies accessible”.

Q: Out of all the institutions which offered to acquire his collection, including the NYU library, why did Mr. Kim choose Sicily? Talk about his motivation so that it finally ended up in Salemi?

DR: Well, I can only tell you what he told me, and it’s all on tape. He said that New York City had multiple video stores available, so in a way, New York was spoiled. They had access to more movies. There are cinemas everywhere. He said his main motivation to deliver the collection to Salemi was that they didn’t have a single video store within, I think, a hundred-mile radius. He wanted to believe in the vision of Vittorio Scotti, that he was going to renovate this entire town and transform it into an artists’ colony and put Kim’s Video at the center of it. I think Mr. Kim attached himself to that vision, and wanted to see Kim’s Video help “start a renaissance”, in his words. That’s Mr. Kim’s — he has big dreams, big visions. This didn’t seem silly to him at all. It seemed like a challenge.

Q: Youngman Kim is very charismatic, but when he operated Kim’s Video, he was like a shadowy presence while there. How do you describe his character after working with him, particularly when he was in Korea— when he was in the U.S., it required different diplomatic processes.

DR: In Korea, he was extremely friendly, but people were also very deferential. He would just walk in and people would know who he was and why he was there. They would take him to wherever he wanted to go. I don’t really understand the cultural signposts of Korea. I don’t want to say too much, I can’t. I wish he was here. He’ll be here tomorrow if you want to meet him.

Q: This film is [about] not just this one particular store, but also about the bygone era of people going to the video store to rent and buy TV shows and movies. What are the things that you miss about the video stores that don’t exist anymore?

DR: Well, though streaming today portends to offer a wide variety of movies to watch in your own home, it’s also isolating. It’s like hyper-individualization. You just sit, consume, and if you don’t like it you turn it off, you get disrupted. You do the same thing with a VHS player, but mostly, we didn’t do that. I miss the physicality of the analog, the human experience, the effort to go and search for a movie — the physical exertion of going to a location far away, finding the movie you wanted, and then discovering 50 others that you never heard of. And then [there was] talking to the employees about what they’d recommend, what they found interesting. And then there was meeting people there who then become your friends; it’s a hub. It connects; it creates a diaspora of Kim’s Video around the world. I think that’s what’s so central about it. Streaming just doesn’t do that. There’s no effort. You just search online, you sit, and there it is.

Q: This film was also selected for the Sundance Film Festival as well. Did you have the premiere of this film? How was the reception there?

DR: It premiered at Sundance on opening night. We’ve played at Copenhagen and several other festivals.

Q: Talk about the personal experience so far. This was a very particular video store in New York, but at the same time, there were tons of video stores all over the world that might relate to this collection of movies.

DR: It’s funny, because I don’t refer to it as a “documentary.” I like to call it a movie about movies, but it’s also a mystery movie. It’s a heist movie, it’s a comedy. It takes a bygone era seriously. The reception at Sundance was stunning. People were laughing in a good way, not at people but with each other, and understanding the nuances of the movie. I was just blown away. I couldn’t believe it — finally, this happened, after six years [in the making].

I would like to think it’s a movie unlike the many other documentaries we’ve seen. Many have political motivations, ideological motivations, and this one is supposed to be light-hearted and fun. It takes you to unexpected places that could be dangerous, but may not be dangerous; it could be an obsession — is it real or a figment of my imagination and fear? Am I living inside a movie, this movie that I am making? This becomes my own movie, and I have to get out of the making of the movie, so it’s like a trap. That’s how I see it.

Q: When you visited Salemi, Sicily, you encountered problems with political issues and mob connections such as Vittorio Sgarbi and Giuseppe Giammarinaro. How was the experience shooting in Salemi. What were the challenges that you faced over there?

DR: The challenges? We have to be very careful. We had help. There was a man named Fabrizio, he was very helpful. Someone told me, “You have to understand the way we communicate.” That’s what he told me. I asked him, “Can you help me, get me access to Gemarinaro” And he went, “What I say, I don’t mean. Look at my body and you tell me.” So I thought, okay, that’s a very touchy subject is what he’s telling me. So just be patient, but that’s not what the movie’s about. Stay focused on Kim’s and trying to get the collection back in New York City.

Q: This film is such an immersive experience and at the same time you get nostalgic about this film. What do you want the audience to take away from this movie?

DR: I hope they go on this journey, to understand the unexpected twists and turns of the movie, and then ask themselves, “Is this real? Did it really happen?” That’s what people have asked me so many times: is this real? There are some journalists who indicated that I actually set up the break-in. I called Enrico ahead of time. “Okay, I’m going to break in, and then you come. “ That’s what I like — it’s difficult to understand if the movie is a “mockumentary” — and I’m okay with that. I don’t take that as an insult — if [they see] it’s as a documentary, or if it’s a movie. It invents its own genre like a very important B movie at Kim’s Video. That’s what it is. It’s shot like one, it’s shaky, like an old camera that we used 10 years ago. It looks like a movie that you would find on the shelf at Kim’s Video and you’d say, “What is this?” Then you watch it and say, “Wow, I never heard of this movie. I’m glad I watched it. It changed me.”

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.