Synopsis : Two women, Janis and Ana, coincide in a hospital room where they are going to give birth. Both are single and became pregnant by accident. Janis, middle-aged, doesn’t regret it and she is exultant. The other, Ana, an adolescent, is scared, repentant and traumatized. Janis tries to encourage her while they move like sleepwalkers along the hospital corridors. The few words they exchange in these hours will create a very close link between the two, which by chance develops and complicates, and changes their lives in a decisive way.

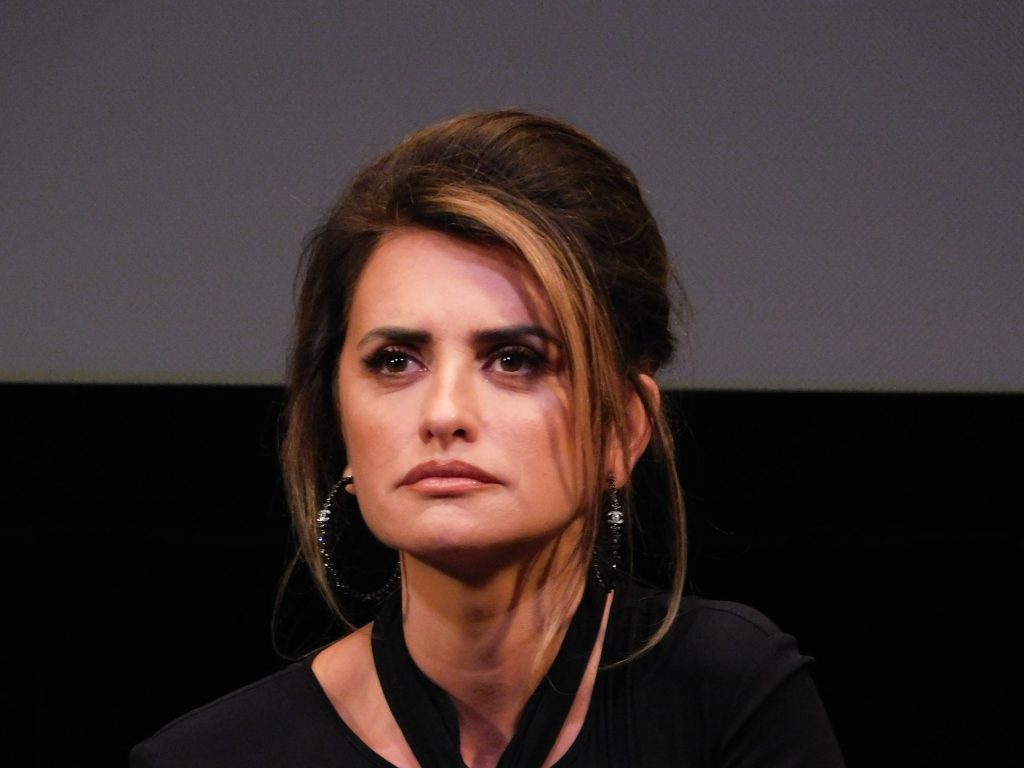

Press Conference with Director Pedro Almodóvar, Actress Penélope Cruz, Actress Milena Smit

Q: Thank you for showing us the movie earlier this summer. Dennis Lim and I were able to watch the film in Madrid, and once we saw it with you, we knew we had our Closing Night. So it’s special for us to have you presenting it. Thank you for coming, and traveling all this way despite everything to be here.

PA: Thank you.

Q: So I’ll just dive in with a couple of questions to start and then we will take some questions from the audience.

I think, Pedro, it might be good to start with some historical context. This image at the end of this film is one of the most striking of the images I’ve seen in all of your films. It’s such a striking image and it represents so much. So if you want to share with us a little bit of historical context, I think it would be useful for us to hear from you about this dark chapter in your country’s history, and why it was something you wanted to explore.

PA: This is the more explicit political movie that I did. The protagonists are these two ladies, it’s about them. But I wanted to create a link between the protagonist Janis with the past because this is what I’m talking about – about the darkest side of the Spanish civil war.

[in Spanish – translated by his interpreter ]

The link that I create in the film between the history and the main character comes through her grandmother. She’s an orphan, her grandmother has raised he, and her grandmother has told her the story of how her great-grandfather was killed and has left her this legacy. This desire to find his [grave] and exhume his [body].

So this is the way in which I link someone who belongs to the present day, like Janis, to the history that happened 80 years ago, which is through her relationship to her grandmother and the legacy that she has left.

The central axis that I set up in the film – I really wanted to talk about the mass graves and in this particular case, about the truth about them and the truth that the character is seeking that of course goes in contradiction, as you have all seen now in the film, to the way in which she’s handling truth in her own life. So this axis, this contradiction, is something that the character needs to come to terms with.

PA: Yes, to the end, because perhaps you don’t know: Spain is the second country after Somalia with more missing people. Actually, now it’s like 140,000 missing people that are courtesies. The Spanish society has a debt with the families and with the victims until the moment that they don’t open all those mass graves. I think that the civil war is not ended. So we need to do that just to close that awful period of our history.

Q: How is this subject discussed right now in Spain? Is it discussed?

PA: The movie happens between 2016 til 2019. Now – I mean last July, three months ago – there is a new law by the Socialist Party, which is in the government now, and that completely changed the situation. Now the administration that takes care – the name of the law is the “ley de memoria democraticum” and everything related [to] mass graves is a question para el estado, for the state. It’s a question for the state administration organization.

Interpreter: So through this new democratic memorial law, the state is now in charge. The administration is now in charge of taking care of the graves. So everything will change from this point on.

Because during the time period that the film takes place, those in charge are really private enterprises or NGOs that are having to take care of these cases.

Q: I want to bring Penelope and Milena into the conversation. Welcome, welcome back.

So Penelope, I would love to know how does this collaboration work? Does Pedro just call you up and say “I have another movie for you” or does he just send you the script? In this case, how did the conversation begin, specifically?

PC: It can happen in different way, all of them magical for me. The first time he shared with me something about this story, we were here in New York, doing press for “All About My Mother”. He told me a few things about the story that later changed, evolved a lot into something else. But that was the root of the story.

Then when we were in total lockdown, and confined in Madrid, we did one of our calls, and we did a face time, and he told me, “Oh, by the way, I took this story out of the drawer and I’m writing it again and I’m thinking about you for the character.” Imagine during lockdown with all of us like, we didn’t know until when, what was the future, what kind of future, and we had no idea. We didn’t. We knew nothing.

And then he gave me this injection of hope and excitement, and knowing that that would be the plan in the horizon, for us to do this wonderful story together. So maybe from all those times that he has shared those stories with me, [the] news with me, this is my favorite because it was during extreme circumstances.

I think we all need to have faith that at some point we all would be able to get out of the house again. First of all, that we would make, it, that we would survive. I mean, I was terrified; we didn’t know. I took it very seriously from the beginning. And then we didn’t know if it was a plan for a year later or five years later. We had no idea. But I will always remember that phone call.

Q: When you showed us the film this summer, Pedro, one of the first things I asked you was how you had been spending your pandemic. Because clearly you had made two movies in the course of just 18 or 19 months. So you clearly just focused yourself on work to navigate this time period.

PA: Yeah. For me, it was the only way — just to write and to shoot. It was the only way, like an escape from the reality. It surrounded me. I could see on TV and in the newspapers huge tragedies happening every day. But I concentrated myself in writing. Actually it was more productive than before, because during the three months of the confinement, I could be much more concentrated in the writing. Because as I could go out, I didn’t see anybody. And it was the best way for me to finish the script.

Because it had a long time of cooking and there are many things that I didn’t like at the beginning. So I could find out everything and finish in these three months. Just when the confinement finished then I start, because this is what I was doing during the last free week after confinement. Tilda Swinton was already in Madrid just for the rehearsal of “The Human Voice”, so we had to postpone it, of course.

Then we took it again at the beginning of July [2020]. So we made the pre-production and then during the pandemia we shot the short [film] that is thirty minutes. We were very lucky because we [had] not one case of being infected. My brother, who is also my producer, hired a sanitary team. He made us [have] a PCR every day to be sure that nobody [was infected] because it was the only way to be sure immediately.

With that we shot “The Human Voice”. We went to Venice, we were very successful. Then immediately after Venice Film Festival, we started to pre-produce “Parallel Mothers”. So I think it was a more fertile time for me and I think it was because I preferred to be just working on

Of course I was sensible about everything that was happening there. And also it made me suffer . But I did not want to be obsessed with this situation. In general, for me, to make a movie is always a kind of run away from my life. Even if there are not tragedies, like here with the pandemia. But it was always that [it] drives me to another reality where I feel much better than in my own life.

Q: It gives you more control maybe?

PA: Yeah, yeah. For example, I feel, when I’m working, when I’m writing and shooting, I’m feeling much more free than in my real life. I don’t know how to explain it. The reality that we live day by day, I’m not so curious and so daring like when I write or when I am shooting. I’m more like a coward.

Not exactly, I mean, I don’t have any word because my English is very limited. But yes, the moment when I feel completely free — and this is a wonderful experience — it is when I’m writing. There [are] no limits for me.

Q: Does this resonate, Penelope? You’ve known Pedro a long time. These two parts of his life: the professional, the private. Do you see this dichotomy with him?

PC: Yeah. I’m not with him when he’s writing – but he’s writing all the time. Even when we are traveling promoting one film, he’s sometimes writing three scripts at the same time. I don’t know how he does it, but [it’s been] like this since I met him. But I can tell when we are shooting and when we are not. When we are shooting, I think Pedro is happier. When writing, shooting, in pre-production, post-production, traveling around the world with the movie, I feel that he’s happier in those processes. And I understand because I identify with that.

PA: Well, you have a life. You are a mother. You have a husband.

PC: I have a life that makes me very happy, but even like this, even if I have children – that you know I’m obsessed with, and they are the best thing I have in my life. I am a family-oriented person. I’ve always been like that. I value that very much with time in my family, and raising my kids is my priority.

But it’s true that I’ve been doing movies since I was sixteen, and I understand what happens when you wake up in the morning and go to the set, and you just feel complete. We only have that as actors we can have it more often. Maybe we can do a couple of movies per year or three if they are not too long.

But for a director, I understand it’s different. Everything is a different timing. So that’s why I say, in his case it’s very obvious for the people that know him as well as I know him, that he’s so much happier when he’s working. So I’m telling him, “Every summer we have to be shooting a movie.” Write in the winter, then we’re very quick at editing because everything is so clear for him. Every summer, we shoot. He likes shooting in the summer.

Q: Penelope, congratulations on this performance. It is an exceptional portrayal of this woman Janis. Tell us what struck you about Janis, what interested you in this woman? What drew you to this role?

PC: Everything from the first page – I was hypnotized. I use that word a lot with this film because I think it happened with the script, and it happens when you watch the movie. It has an incredible hypnotic effect. You’re there and it keeps you so present and so there, you don’t want to lose anything. It is so many details. It’s a movie that if you watch [it] two or three times, you always will discover something new. I think he created something really, really special.

When I read it, I felt like once again, this is a perfect script and he’s giving me an amazing opportunity with this character. It’s true that all the characters that I’ve played with Pedro have been complex interesting characters, difficult characters. Because a lot of people are asking me if this is my most difficult [role]. But all of them are, because he writes with so many layers that I don’t think we can say any of the characters written by him for men and women are easy, because they are not easy personalities, or simple. They are complex, they are not just one side of them.

But it’s true that Janis is put under so much pressure. When you think one thing is solved, another bigger problem comes into her life, and it’s constantly like that until the end of the film. And that was a beautiful challenge to have in my hands, and I am very grateful that he once again imagined me in doing something that he didn’t see me do before.

He’s done that constantly with me in my career – imagine that I could do something that I never did with him or with another director. That is the best gift that somebody can give you, and if it comes from a genius like him — because I don’t like using that word lightly, but with him, that is the word that makes sense.

I think I can say that in a very relaxed way because it’s just the truth. So to be so lucky to have this constant faith, and all these gifts that he’s given me over and over in my life, I could not be more grateful and thankful.

PA: I was the lucky one. I was the lucky director.

Q: What do you see in Penelope, Pedro, after all this time together?

PA: Well, the first time that I saw her I thought of course –I saw her in her debut, “Jamón, Jamón” [1994]. I remember very well the cinema [where] I saw the movie. I was very impressed, as she was very extremely young. I was impressed about the way she acted. She acted in a completely personal way that if I listen to that voice and that way of acting in other actresses, I thought that it was not in tune. But in her, everything was true and original, and with a kind of incredible strength, even being so young. So when I went out of the theater I thought that “well, this is the actress that I would like to work with.”

Fortunately we met – I don’t know how many years after – and it was mutual, fortunately.

She was always at the moment too young for the character that I was writing. So then we could make it, just to work together, in Lifeless [“Live Flesh”?]. She was very young but anyway, I thought that it was the moment to start. She’s only 8 minutes onscreen and I think she stole the movie [from] everyone.

I don’t know what year after [that] I met Stephen Frears — two years somewhere. He told me that he called her to make one of her American movies, “The Hi-Lo Country”, a Western, because of that eight minutes in “Lifeless”. So since then we really became close friends, and it’s like part of my family.

Also, this is really an advantage you have, that once you feel that you are very well understood by someone and also that I understand her very well, this is a plus that you have at the moment of working. Also, she’s [incredibly photogenic]. This is also very important.

Q: Michael Barker reminded me backstage that when we called to invite the film to screen at our festival tonight, one thing we said was we had to invite Milena Smit to join us at this event. So thank you for being here today, Milena. We’re so excited to have you. Congratulations.

MS: Thank you.

Q: In the old days, there were these legends of actors and actresses being discovered at a drug store or a candy store. In this case, your team found Milena on Instagram. Is this true?

PA: I think for me, Milena in the movies is the big revelation because she was new, and also we all were very impressed that everything she does is true. For me it’s like [being] the witness of the birth of someone that is going to be a big star. Because I am sure that the future of Milena will be wonderful, that she’s going to make many movies, and she’s very young so she will have time to make many different types of movies.

Because also, the way of acting in my movie that could be the more usual is not her, exactly. She’s another type of women. I think she’s also very versatile physically. But I was impressed about her immediate truth of everything she says and she does. So we are in front of a very very near, or very close, superstar.

Q: Milena, same question I asked Penelope: about this character and how she resonated with you. But also, before you tell me that, you get a call from someone in Pedro’s office saying “We saw you on Instagram”, or how did this happen?

MS: [thru interpreter]: Thank you very much. I’m very happy to be here and to be presenting this film here with Pedro and Penelope.

It was through a casting call and I did various tests until the last one which I did with Pedro and Penelope. So I never knew what all those tests were for until the very last casting. My agents did think it was a good idea to let me know ahead of my test with Penelope and Pedro. so we did various tests there at El Deseo.

I had never really read the full script because I only got parts of the script for the tests. During one of these parts of the script that I read which was an inflection point in the film, after performing it I cried a lot. It was shortly thereafter that I got the full script from Pedro with an inscription telling me that I was Ana.

Q : A question about the power of cinema as a tool of memory?

PA: I do think that films, other than the fact that they entertain us, they also play a role in bringing us close to issues that are happening socially [and] culturally. In this case, the people who excavate the tombs, they told me that they really gave me thanks for bringing visibility to an issue that is not talked about enough in Spain.

Now the situation, as I told you before, is very different. We don’t know because the right wing is furious with this law. [It’s] something that I really can’t understand because it’s a problem of humanity. The only thing that the families of the victims are demanding is just to have a place with the name of their grandfather or their great-grandfather; a place to bring some flowers, and to pray, if they are believers.

But the right understand [it as] a political response and they think, like the character Ana says in one moment, that it only will help to open old wounds. It’s not. It is not. It’s a very simple and very human situation.

Q: Let’s take another question: about the inclusion of the relationship between these two women in the film: how was it added to the story? Did it feel very natural for the [actors]? The comment is that it’s like a hetero-flexible, rather than a lesbian, relationship. How do you think about it?

PA: Especially if you pay attention to the end of the film, I try to show the creation of a very open and very heterogeneous family – inclusion, yes. For example, I don’t really explain at the end of the film what the relationship is between them. Maybe they’re still together. I personally think yes. What I want to show is a relationship amongst all of them, including the forensic anthropologists.

They’re both orphans: one because she lost her mother at a very young age, and the other one because her mother never paid any attention to her. They both feel this very deep sense of wanting to form a family.

So the first moment in which they form a family is when Ana comes to Janis’s house merely to take care of the child but they’ve already formed the family unit at that point.

Yes, of course you can label the relationship as a lesbian relationship. But I really think about it as something more fluid and more broad than that, where gender is not so much attached just to that one act of sexuality but that it’s something that happens more naturally, almost spontaneously, between them.

So, for example, I like to think from the very first scene: we’re in the hospital where they’re both pregnant and about to give birth, [and] from the very first moment there’s already an inkling that Ana has been struck by Janis’s beauty. Like a kind of crush.

And if I had to explain and enter into that really painful territory amongst couples where you ask who loves who more than who, then of course I would have to say that Ana is much more in love with Janis than Janis is with Ana.

But you can also say that Ana is much freer than Janis because Janis of course has this internal conflict because she knows that she’s hiding something from Ana. But from that very moment, they’ve already formed a family.

And things have changed a lot over the last thirty years in Spain. Yes, traditionally, perhaps, or in the sense of a Catholic family, but that has changed profoundly in Spain. Really, what has happened is that the family structure is more a vocational [volitional?] family structure, one that is really based on love, so that you can have families made up of one mother, or two fathers, or two mothers. It’s more about the love and the vocation for family than anything else.

Q: Penelope and Milena, did you think about the labels for these two characters’ relationship, or labels for this family? How did you talk about it?

PC: I try not to think of labels, especially when I’m working with Pedro. It’s like when you read it, there are no labels anywhere, and it’s one of the things that I love the most about the way he creates and about the way he sees life. And I really identify with his way because I’ve been raised like that.

So I didn’t have to find the etiquette of – what are they called, because right from now on they’re going to also have sexual relationships. It goes beyond that because if you think about it, when Ana kisses Janis the first time it really catches me by surprise. But my character is in such a survival mode that I could hear the thoughts of my character.

I have very good memories of that scene because I feel like we really were not there, it was only the characters. And I could feel the thoughts of Janis and they were like – I could not share them with you now, it’s not like I remember the words. But I remember the feelings. But actually, this is right as a next step for survival.

And of course Janis has a connection with her also in that way, but it’s not just about sex. It’s desperation: she always wanted to have a family, and she never could. Maybe this is going to be the way. Maybe this is the next step for her not to lose what she loves the most. And she’s threatened by the laws [loss?]. And actually, this could be the solution. Its not like she’s forcing, like oh, she wouldn’t go to bed with her if she didn’t feel something, but it’s beyond that. It’s like almost unconsciously [she’s] a lion protecting that family.

I think all of that is in that shot when you just see the face of the two of us and what everyone is thinking on this: Let’s go. Because I’m not going to be alone again, I’m not going to lose this family again.

So it’s so many things going on in my head in that scene that the last thing I was thinking was “How would we label this relationship?” I had no space for that.

Q: Milena, same question.

MS: I really agree with Penelope because of course, in the case of my character, what I really sense is that she is lacking love, she’s lacking a kind of effective connection, given her situation with her parents and also the traumatic situation that she’s been through. Suddenly she finds herself in front of someone who’s giving her more support and more presence than her own family has.

And I really do think that we make a large mistake if we tried to place a label on the situation. For her, what happened between them was just really, truly an act of love. I think really that’s fundamentally what describes a family, right? Is love. So for me, what happens between the two of them, we would make a mistake to add a label and call it a lesbian relationship.

Q: Question on balancing the nature of women as victims and women as heroes:

PA: They’re fighters, first and foremost. If I just go to the case of Penelope who in the film is a mother, a single mother who has to balance motherhood with her work life, and that already is something that is not easy.

And yes, it is primarily, for some reason, women who are searching for their relatives. The direct victim, of course, is the person who they have lost. But they themselves have been victims because the state has not given them the possibility to find their relatives. And they’re also victims of democratic Spain.

During the 40 years of the dictatorship, the families never spoke a word. They were too afraid. There was this enduring silence and this pathological fear. Once Franco died and the amnesty law of 1977, which is also known as a Pact of Forgetting [was passed], Spain now entered into democracy. At that point the Socialist Party was very careful and attempted to be very pragmatic, because there were still a lot of Francoist elements remaining in the other parties.

Because they were frightened. In fact, three years later in 1981, there was a military coup d’état so at that point even the left forgot the victims. So the victims were condemned by Franco to a kind of non-existence. But then also the Pact of Forgetting under the amnesty law also condemned them to a non-existence.

Even though I sympathize with the Left, because it was something necessary for the transition, it is true that the ten years after this moment, once democracy had really established itself the left should have looked back and tried to remedy this mistake.

So I think that from that moment on, Spain really has a debt to its own past and to the people who have lost loved ones. Through the course of the last 40 years, it’s not like the victims have not been remembered. They have been remembered, but there’s always been this element of fear. It’s not until just now, the current socialist government finally they’re doing something concrete to remedy the situation. So now it’s the generation of the great-grandchildren that are asking for the exhumation of the graves.

Q: Pedro, Penelope. Milena, thank you for sharing the movie, thank you for being here.

Here’s the trailer of the film.