Synopsis : Hirayama seems utterly content with his simple life as a cleaner of toilets in Tokyo. Outside of his very structured everyday routine he enjoys his passion for music and for books. And he loves trees and takes photos of them. A series of unexpected encounters gradually reveal more of his past. A deeply moving and poetic reflection on finding beauty in the everyday world around us.

Genre: Drama

Original Language: Japanese

Director: Wim Wenders

Producer: Koji Yanai, Wim Wenders, Takuma Takasaki, Yusuke Kobayashi, Reiko Kunieda, Keiko Tominaga

Writer: Takuma Takasaki, Wim Wenders

Runtime: 1h 59m

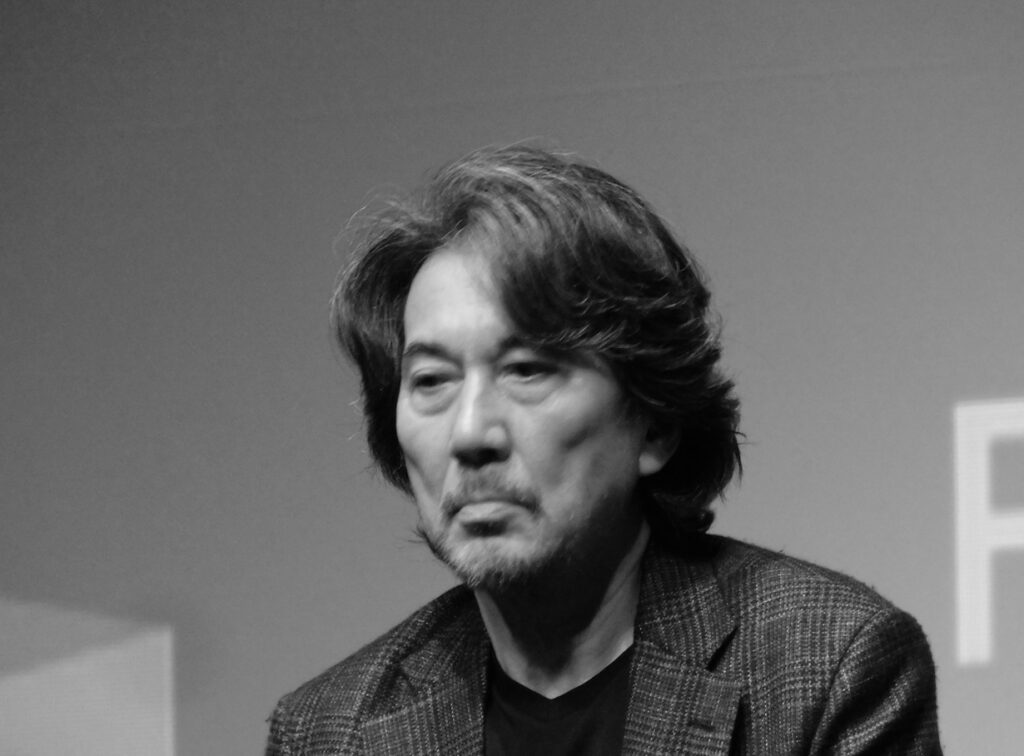

Q&A with Co-Writer/Producer Takuma Takasaki and Actor Koji Yakusho

Q:This part was written especially for Koji Yakusho — how was your preparation for it?

KY: I’m just so grateful that Takuma and Wim Venders wrote such a wonderful script for me. I’m extremely blessed and the most important thing in preparation was to learn how to clean the toilets properly [laughs].

Q: It was a quite fast process of writing how was it to work with Wim Wenders and how was it working on the construction of the script?

TT: when I first spoke with them we had discussed doing a fictional character — a fictional existence in the form of a documentary. First, there weren’t very many lines in the screenplay itself. My daughter actually wondered — “Are you really working, dad?” One thing that Wim and I took great care [to do] and put effort into was writing things that wouldn’t necessarily be seen on the screen; they might not be visible. In order to create images for things that aren’t written in the screenplay it really had to be Koji Yakusho as the only person who could accomplish that.

Q: Koji, you mentioned that you learned how to clean toilets but the character has a big dimension and a past. Tell us about how you conceive the character not only in his actions but also in the emotional dimension as well?

KY: There were very few lines in this beautiful place. A beautiful script but to get closer to the character, I really just thought about how he cleans these toilets every day. He goes to the forest and eats his sandwich, takes a bath and then he goes home. He reads a book that he loves and he goes to sleep and so I was thinking about this man and just pondering who he really is.

During the shoot was where I did a majority of the work that you were asking me about. As Takuma said, this was like a documentary in a way, because there were no rehearsals. We would just shoot and would go straight into shooting takes. It was as if I was just living as him and as we were shooting. I knew that every moment was not going to be repeated so I just cherished every moment and I think that’s what you see on screen.

Q: Is the routine a shelter for this character – shelter from pain, from the past?

TT: The answer is yes, maybe in a way, but what I found is that it seems like in his repetition of everyday life, he still sees and hears things differently every day. So every day is really fresh for him and he feels that these things really reach him. I think he’s moved on a daily basis by the really subtle changes that he experiences and that’s just who he is. He’s a very happy person and especially when his past comes to greet him in the form of his family. He’s moved profoundly and I think he’s even further cast into sort of the depths of who he is — he’s much freer at that time.

Q: It’s interesting that you both mentioned the idea of documentary because in a way it’s a document of Tokyo, of certain places ,of a certain rituals, but at the same time the film has a fictional aspect even when it was shot as a documentary. Could you comment on the dreams aspects of this?

TT: It wasn’t that he was forced to live that kind of existence; I believe that it was on his own that he positively chose to live that kind of life. In terms of his daily existence, every day for him is fulfilling so I think that that feeling is reflected in the dream sequences that’s an expression of what he’s feeling.

Q: The music is there from beginning to end. Were those inclusions written or were the specific songs decided on once you were editing?

TT: The [music] was actually part of it at the stage of the script writing. I’m sure everyone here knows how Wim Wenders is, in terms of his inclusion of music in his works. I would say that he’s probably the world’s leading director in terms of that technique but what we actually discussed almost on a daily basis is what would Hirayama be listening to.

What kind of music would he be a fan of and based on that, we together chose the songs that would be in the film. At the time of the script writing, we basically had a list of what music would be included. Something that was probably the most surprising or incredible that I thought was there in terms of the list of music was that our director decided very clearly that we would not use any music that Hirayama, the person or the character, would not be listening to.

Q: This music somehow belongs very much to all of us but to a certain generation most especially. The film talks about a dialogue between two generations or a different way of approaching work and life observing nature having a different rhythm. To both of you, was there a certain idea of a melancholy of the past, a certain criticism of the present or was there a way to find the tonality in the conception of the whole film?

TT: In terms of approaching the existence of Hirayama in the same way, it wasn’t that we were trying to create a sort of story or create this portrait of him where he’s rejecting certain things or criticizing certain things. It was more of a positive portrayal in terms of how he lived his life and his actual existence itself so it wasn’t that we were intending to create this agenda or anything like that. We were very carefully following him almost as if you were an interview subject. In looking at him as a person and what he would do, again there was nothing intentional in trying to create this contrast or criticism

KY: When I first saw the film completed, I saw Hirayama’s life and thought, “Wow he really has no fortune, nothing to go by his name but he goes to sleep every night extremely satisfied.” In Tokyo or New York or any big city, you can basically buy anything that you want in terms of material possessions but it’s not where you find satisfaction.

Seeing Hirayama in this concrete city with no TV or internet, he just sees and hears what naturally comes into his life. It’s like he’s living in this very pleasant forest even though he’s living in the middle of a massive city. I was just impressed and taken by how he lives and just felt myself fall into the thought of, “Wow, there’s a way to live this way in a city.”

Q: It’s interesting that you mention this contrast between material life and the word “consumerism.” The spiritual aspect of the film shows that and maybe the most emblematic character for this is the homeless person played by Min Tanaka. Could you comment on this character and this amazing actor?

KY: I would say that Hirayama sees this homeless man, but maybe he actually doesn’t exist in reality. Most people see homeless people but pretend not to see them and I think Hirayama is able to see him. He has this special connection with him because this man sort of expresses “Komorebi” — which means, literally, the light that trickles through the leaves of the trees and casts a shadow. Min Tanaka, through his dancing, sort of expresses what Komorebi is. I think Min Tanaka is an absolutely incredible dancer and actor — someone that I really respect deeply.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.