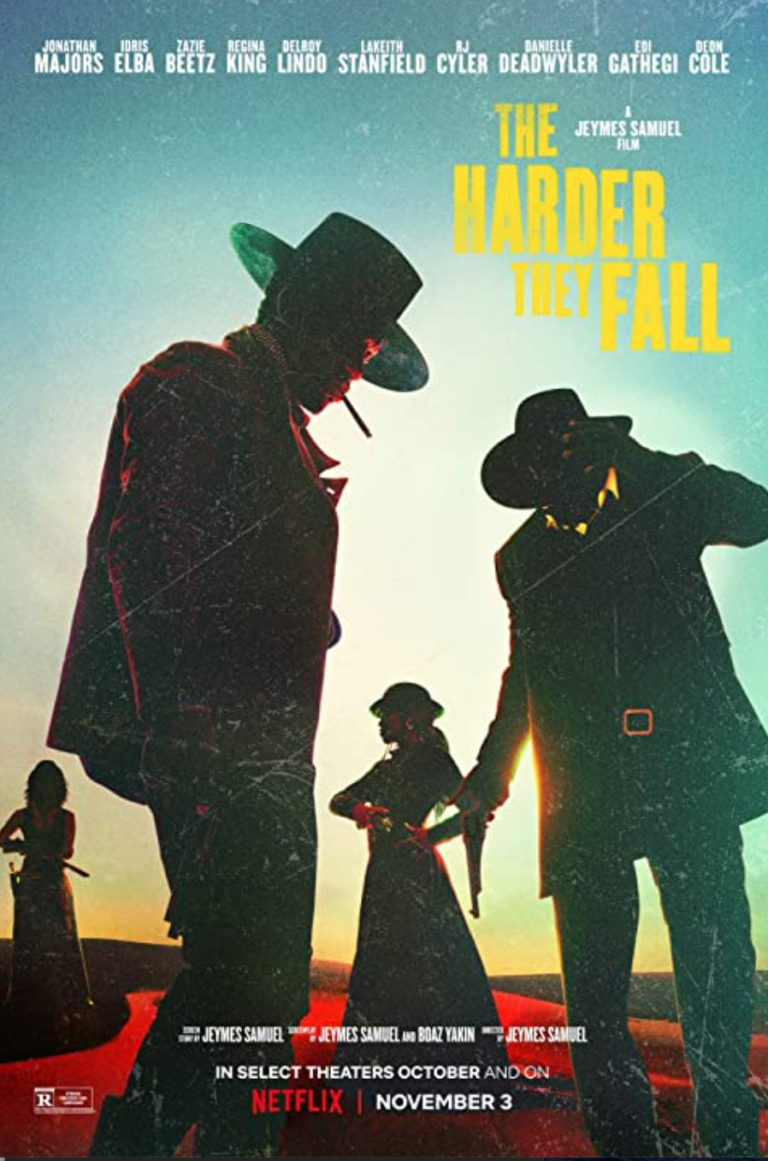

Synopsis : When outlaw Nat Love (Jonathan Majors) discovers that his enemy Rufus Buck (Idris Elba) is being released from prison he rounds up his gang to track Rufus down and seek revenge. Those riding with him in this assured, righteously new school Western include his former love Stagecoach Mary (Zazie Beetz), his right and left hand men–hot-tempered Bill Pickett (Edi Gathegi) and fast drawing Jim Beckwourth (R.J. Cyler)–and a surprising adversary-turned-ally. Rufus Buck has his own fearsome crew, including “Treacherous” Trudy Smith (Regina King) and Cherokee Bill (LaKeith Stanfield), and they are not a group that knows how to lose.

Q&A with Actor Jonathan Majors

Q: You’ve described it as a spaghetti western. It’s definitely unique in the way it exists in that space. What first drew you to this role? What made you want to sign on board?

JM: Oh, wow, so many things. The script is probably 123 pages, and the first 13 pages are flashbacks, where you see young Nat, and that’s what got me. It’s the first time I read the script and went, “Oh man, I really have to look after this kid.”

It was broken down to me that I was potentially going to play the older version of him. When I saw what happened, I saw the violation of it all, and how tall the order was for him to redeem himself, to heal himself from that scar, I was all the way in.

Then we hear that Jay‑Z (producer) is going to be on it. And you hear that Idris Elba was going to be in it. Idris was actually the first actor on the film, so I knew I was jumping in with him. But even then, even then, you want to be particular about it.

Q: This character is on this revenge crusade for the trauma he experienced as a kid. He’s also a person of complexity, though, in that he is an outlaw, he’s still a criminal, and that’s what he faces in that final scene, the dialogue with Idris. What about the shades of him? How did you hook yourself into that? What was your entry point?

JM: The final scene, the complexities of Nat — it’s like the trauma of the moment. One of the ways I really got into trying to understand him and how he operated, and move through the West was the fact that this whole thing happened to him when he was 10 years old. So the same thing that grabbed me and I felt led me to play him was the same thing that was going to push and move him through the story.

So that Love, leader of this gang, is a 10-year-old. That’s a cheat sheet – he’s operating from that space, and the fear that he experiences in that moment – in the taking of his parents — sticks with him. It’s in his bones, that’s the blood trauma of him.

And yes, in spite of that, he falls in love with Mary and there’s a whole incredible backstory of that. He finds Jim and Bill, and these guys become running mates. He yells out something about him where Cuffee — Cuffee is an interesting way to look at it, because he doesn’t know Cuffee. Why does he allow this individual into the fold, why is that?

Well, the whole thing for him is fairness. When you’re ten years old, when someone takes something from you on the football field or the playground, you’re screaming and yelling because it’s not fair-it’s not fair-it’s not fair. We have this deep understanding of justice inside of us, I think, from a very young age, and everything Nat does is in an attempt to make it fair.

Q: How is that connected to your question? I can’t rob an innocent person in the bank. That ain’t right. But I can rob the motherfuckers who rob him. That makes sense to me. That’s fair. I can’t kill a man in a church — definitely not Nat, the son of a pastor. But I will, if the money you get to keep you holds to that. I already did my business. That’s fair, that’s even.

So in the final scene, the interesting part is that Nat has to listen. It starts from the beginning. He walks in and “I got ‘im.” “Shoot him, shoot him, shoot him, shoot him, shoot him, shoot him.” Right? But his back is turned. That’s not fair, is it? I can’t do it.

Nat has so much discipline in that. He left his gang, and he left Mary when Rufus Buck was released. Those are the rules. And that’s why I found the scene so interesting, I think.

There was so much internal annex to a conflict because he knows what he needs to do: just finish it. But he can’t because there is something deeper and stronger and fair in him, and so he has to listen to the story. He has to find all these things out, and when he hears why Rufus did what he did, it sucks, because that lines up with fairness. When you do what you did, you do what I would have done. You do what I’m doing.

Q: Look at the host of roles that you’ve had over the last five or so years — each one is so different from the next. Do you feel you’re looking for that kind of hook with each role? Is that something that you’re keeping your eye out for when you’re reading a new script, in terms of how you’re going to break it down, what the character is going to look like on screen?

JM: Absolutely. I could say it’s all these strings, but it’s just by the books, you know what I mean? The character’s objective behind all those things. But after all that, there’s this other element. There’s this other thing that, “Is that a girl?” There are all these other elements to it.

So yeah, I look at a character and I go, what’s the secret? What is the secret that this character is going to offer me? If I spent enough time with you I could figure out what your secret is. And that’s what I attempt to bring to a character: to tell that secret.

No one would think an outlaw is a gang leader, is a bank robber, operates and thinks like a 10-year-old boy. How many of those hard men do you know in the world? Think about that.

So the homie sees it and they go “Aw man, they turnin’ onto my business.” But I got the cheat sheet, didn’t I? I figured something out, or maybe I’m trying to express or explore something. So within my character I feel like there’s something like that to him. We’re not that complicated, I don’t think. He wants to make it fair. That’s it. That’s it.

One of my drama teachers would say, “How would Jerold Freedman (in North Carolina in the schoolyard) – How does this character buy a bottle of wine?” Makes it fair.

Nat Love walks in there and buys a bottle of wine. What is he going to do? “Okay, so who sells the most? Who sells the least?” I know which one he would buy. You could figure it out. You know how that scene would go. Same for all the other guys that I’ve been fortunate enough to play.

Q: I love the breakdown of that. You mentioned your training, UNCSA, you also went there for undergrad and then you went to grad school at Yale School of Drama. You’ve spoken before about your training being a DE training, something that’s going to break your habits as a performer. Can you expand on that a bit? What place do you hold that foundational training in yourself today?

JM: You step into it now. Here’s the thing about that.

That mantra or mentality only came to me afterwards. I came into NCSA at eighteen, I was delinquent, I got in trouble, I had straightened out, but I was pretty much — the instrument’s very raw at that moment. Everybody, you can try and be as polished as you want to be at 18; it ain’t gonna happen, Jack. It’s just not real. (No disrespect to any brilliant 18-year-olds.)

So they took all that, and they give you all these constraints — compulsives, rules, get to the end of the line, all these things you learn technically. It’s very helpful. But then there comes a point where it no longer serves you.

But it no longer serves you because it’s now a part of your subconscious, which means you really would have had to have done it. I’m going to say it one more time: you really would have had to have done that. Anything. You’re playing a sport, you can’t act like you dribble, you’ve gotta dribble and really know how to do it. Driving a car: you can’t pretend to drive a car.

Q: It’s like a muscle memory, in a way.

JM: It’s a spirit memory. You see? And that’s the thing about acting training, which [can] get a little crazy.

So after NCSA, I thought I was hip to it. Something ain’t right yet, you know, like I didn’t feel like I was where I wanted to be as an artist. Sanford Meisner says it takes thirty years to be an actor. I’m 32.

Then from there, I go to Yale and I go, “Okay, all this… I got this now. I understand that this is a part of my lifestyle.” Acting, being an actor, being an artist is a lifestyle. That’s why I’ve been untaming. Where it’s like now, you actually know how to fill your instrument up to full capacity, to express yourself. So if you choose not to do that, with your barista, or with your lover or with your friend, that’s on you. You are actually taming yourself.

You sat in the class — similar to this — with your shoes off, and cried and breathed to work all this crap out, to be able to do that. So the journey at Yale was very much – I was really having my heart go, the whole time I was there, for multiple reasons. But primarily because I was doing it right, you know what I mean?

I think you have to rage against the machine as an artist. It’s just a part of it. That first machine is the society that you grew up in, and the constraints you put on yourself as an artist. As a young black man from Texas; as a young father. All these things. There’s all these constraints I put on myself and you have to contain all those things.

So I guess, in a nutshell, what I’m getting at and what I hope actors that do decide to go the training route – which I did, so I can advocate for it – but if you don’t go, there still has to be a balance. There has to be some type of balance, and the plays will give you that.

The plays will give you that. If you do it properly – if you do an August Wilson properly, if you do a Shakespeare properly, don’t be all artsy-fartsy before you’re ready. Just stick to the iambic pentameter and get that shit down, and go on about your business.

Q: In terms of this film, with obviously such a star ensemble, you have so many great actors. You shared the screen with some of them before. You’ve spoken before about the process of acting. It really is just about you and the person that you’re acting with, and it’s about forfeiting or surrendering the unnecessary in a way. How do you build that with new collaborators? What is that relationship like on set? When you’re acting opposite Regina King for the first time, what kind of dialogue do you find it’s going to be on the day?

JM: I’d say a wild animal doesn’t need to be taught how to be a wild animal. I think to the point of what we were saying beforehand, Regina King don’t need collaboration. Not from me, at least. I’ll give two answers for that.

One is, you keep an open dialogue, know your work, always know the script, know your character. The cheat sheet is that your character is only your character because someone else is there. I’m only an actor right now because you’re a moderator. If you’re not here, I’m just some fella. Unless all you guys are here. You’re so dependent on who you’re in the room with, so that idea activates a certain moment of vulnerability.

And then the other part is, open heart, open throat, for the times, all the time. If you show up, that love has to show up, and that love can only show up if I’m showing up fully. And then the collaboration can start. A lot of things don’t need to be discussed, in my opinion. Actors have different processes.

Like my friend over here. We did a film together, another ensemble, different group from these guys. When we had to talk, we had to talk. It was like a moment. It was like, get in here, let’s figure this shit out.

But for the most part, what we do as actors is so – I don’t like it to be so bold sometimes. I can talk craft; I can say that’s literally not how that goes. Other times it’s like “Oh, I didn’t know that.” But usually when you’re “huh-uh”, it’s because that artist or that actor is being very tame in themselves. They’re not being full.

I’m saying that for myself, too. If I’m off the mark, it’s because I’m tight in some way. I’m trying to control something in some way. So the training gave me techniques to go “Just release that.” I know how to release that. I know I’m angry about the barista — I don’t know why I’m talking about this barista so much — I know I’m angry about this barista, so let me just unclench this, breathe, and go about my business.

And that’s how we worked on “The Harder They Fall.” Everyone was very open. Playing Nat, it is important to lead by example. Everybody is free.

I will say this, though: it’s not a safe space on a set. It shouldn’t be that way. It should be secure. You should feel secure. But you should not feel safe. It’s a different thing there. If I get with Regina King, if I try and make her feel safe, I’m dealing with her, and I’m not dealing with us.

Safe is, okay, I’m not going to let you fall. Secure is, you can fall, I can fall, but we’ll both get back up. It’s a slight difference. But for me, only in that second iteration can we really make anything happen.

Q: So you’re still going to dangerous places emotionally?

JM: It’s the only place to go. Otherwise it’s pretty boring, isn’t it?

Q: Tell us about the physicality of the character. You’ve spoken about the gun slinging and the horseback riding. What kind of training or prep work went into finding how this person moves in the world?

JM: Well, cowboy boots are quite important. Half the swagger comes from the cowboy boots. And in the coat. And that was it.

Yeah, the boots. The boots are a tightrope wire because they are connected to the ground. And you also ride the horse with the boots, and all these things. It’s the accoutrements of the wardrobe. So that was really important, always important, extremely important to me from that.

And he walked around with 12 pounds, thereabouts, on his body. Between his firearms, his hidden firearms, he’s weighed down. We should talk about the horseback riding, and the stunts in that way.

Q: Did you do any of your own stunts?

JM: I did all the stunts. And I did all the stunts so that at some point I could sit here with you and say I did all the stunts.

But why? Why was that important to me? Because it does something to your body. To be able to move like that, on the horse, you have to be open in a certain way. And when you open up in that way, your voice reacts in a certain way. Your face changes.

I think it becomes a lot simpler when you do the doing. Those who don’t know: if you do the doing, it becomes easy. It takes some work to get there. I broke my heel – which, if you’ve ever broken your heel, you’re fucked. You know you can’t really do anything about it. So you just sit there. So it happens.

I did the weekends with Cinco, who’s my horse, and I love that he’s my scene partner for most of the film. You saw we were together the whole time, really. And what it takes, the aggression it takes to ride a horse like that.

I remember in the final sequence, we were going, and then Cinc wouldn’t go. Cinc just wouldn’t go. I was like [whispers] “Oh, Cinco, come on, man. This is it. Cinco, this is it, this is it, this is it. Come on, man, don’t. C’mon.” And then the stunt guy walked up and he said, “Just let him know. Just let him know. Let him know you need him.”

I walked over to him and said “Cinco? We need to go, buddy. This is it.” I galloped him and moved him around a little bit, and we went.

The camera operator went from here [gestures] to here in the middle of the shot. When we started, I was coming down [ride, ride, ride], comin’ comin’ comin’. And right where I needed Cinc to go, and I had him go [ride], and that’s what’s in the film. The scene goes whooom! and hits a gear. We’re off. And I go, “There he is.” And not me, is that love, there’s Cinco. That’s the movie. Now we got it.

That certain amount of aggression, that certain amount of need, was connected to Mary, who’s on the other side of that. And I was saying, “I don’t want to give him too much. I’m not a small guy. I don’t want to just… He’s ready. He’s a stunt guy. He’s tough for it. He’s tougher than me.” So I said “Okay, I’ll give it to him”, and we go.

Q: We learn how the horse rides.

JM: The guys say a lot of whiskey, a lot of cigarillos, but that’s how it goes.

Q: You got pretty Method with the whiskey and –

JM: Well, I had to try it, because nicotine is a hell of a drug. And so’s whiskey. But why was that important? Because, again, that ten-year-old boy, right? What does it mean? Why does he do that? Why does he need to drink? I don’t condone it, I don’t ingest it.

But I would say that when that love is necessary, there to straighten my own [shit], It was never written that he smoked, it was never written where he smoked. Literally, if I felt myself idle too high — light matches, which is not easy, I’ve been there. And that’s an integral part of his iconography and his emotional landscape.

Q: You have a lot of things coming up. You were in “When We Rise” five years ago, knowing We’re going to see a lot more of you. It’s great to see where everything has led so far, Thinking back to those early days as a professional actor, what is something you would have liked to know in those early days that you would tell your younger self?

JM: I’d say two things. I’d say, one, oh this mentality that I had around that time — and still have — is “Don’t audition.” Just don’t do it. When you go in there, it’s not an audition. You know your words, this is your coverage, you’re up. If they’re lucky, they’ll put it in the movie. But you have got to work it to that degree.

You’re going to hurt. This is not a comfortable job, really, not for the spirit, not for your heart. It’s gonna hurt, and it can hurt now, or it can hurt later. It just depends on when you want to take the lick. Hurting now means you take the time it takes to prepare yourself to be the best you can be — literally, the best you can be, for that role on that day.

That’s the audition. That’s not the audition’s coverage.

And then the other thing I would say, to my five-years-ago self — which is something I just realized it really just keeps everything calm and even: you don’t have to do it all at once. It’s quite overwhelming if you think of doing something all at once. Anything.

I do have a habit of memorizing the entire film script before we go to work. But that’s okay.

Q: Did you feed Regina lines to this film when she….

JM: I’m not bullshitting, if somebody went up, I could tell them – and they knew it. Which is why no one went up.

But you don’t have to do it all at once. Any of it. I do that for my own little neuroses, but it’s such a relief when I get to work and I go “Oh, right, it’s just an eighth of a page today. That’s all.”

I already feel hurt because of it. But now you can play and have fun, and do all that cool stuff you think you want to do. But yeah, you can do all that once you’ve put the work in. But understand that you shouldn’t do it all at once. That goes for everything.

Q: One day at a time.

JM: Shit, one scene at a time. One page at a time. One foot at a time. One sip of Bull at a time. As present as you can be. It keeps you calm, keeps you easy. You need that. It’s a long road.

Here’s the trailer of the film.