Jeremy Thomas is a British film producer, founder and chairman of Recorded Picture Company. He produced Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor,” which won the 1988 Academy Award for Best Picture. He also worked with directors like Wim Wenders, David Cronenberg, Nicolas Roeg, Terry Gilliam, Richard Linklater, Jeremy has worked with many distinguished directors from around the world.

He also has extensive experience in co-productions with Japan, including Takeshi Kitano’s “BROTHER” and more recently Takashi Miike’s “Thirteen Assassins” and “Hara-Kiri : Death of a Samurai.” He has also worked with Nagisa Oshima on “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence” (1983) and “Gohatto” (1999), both of which were selected in Competition at the Cannes Film Festival.

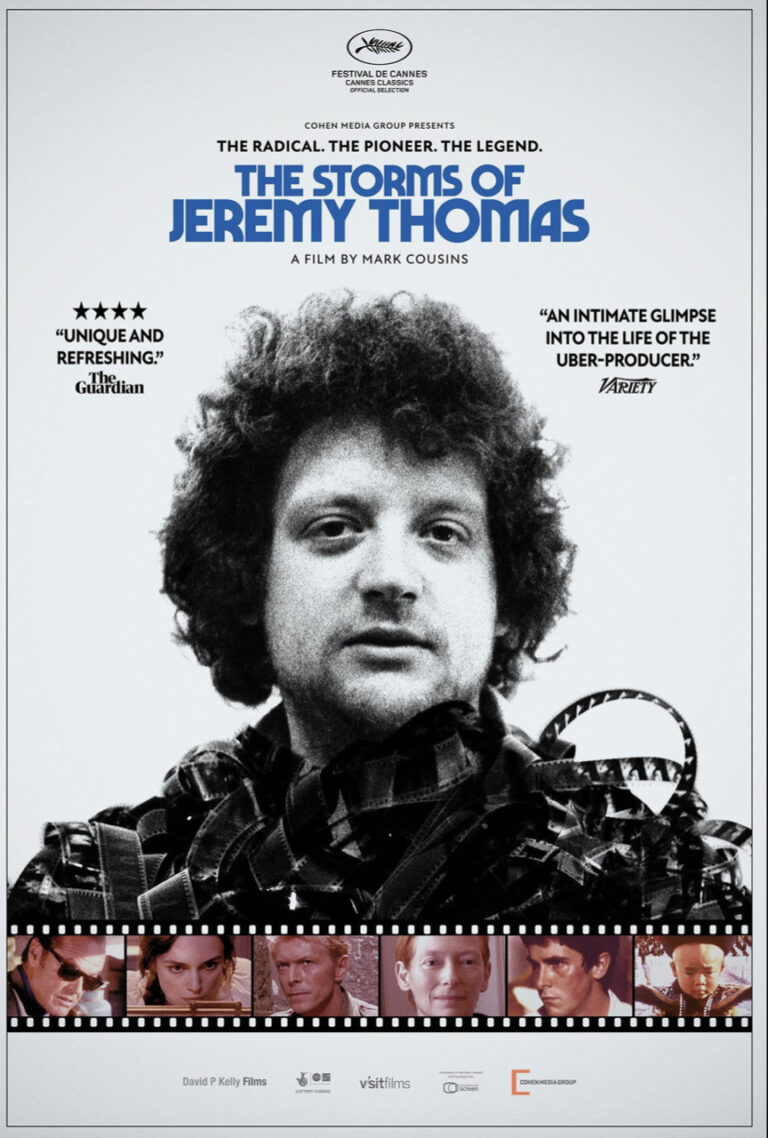

Thomas has been pushing the envelope of big-screen entertainment is the focus of Mark Cousins’s latest documentary, “The Storms of Jeremy Thomas.”

Exclusive Interview with Producer Jeremy Thomas

Q: Your father Ralph Thomas was a director and your uncle Gerald Thomas was an editor, they both in the film business. But after you went to film school you became a film editor. What’s your entry point of the film business?

Jeremy Thomas: Being in the movie business is better than working a regular job. It’s a fantastic life. I saw that so I left school at 17 — I was a very bad student — and went to work in a film laboratory. I only had movies on my mind and was constantly watching films. I was already obsessed with them but I was much younger than when people normally get obsessed. Then I moved quickly through the business working as an assistant editor on “The Harder They Come” by Perry Henzell.

Then I worked with [the late, legendary stop-motion animator] Ray Harryhausen. I worked with Ken Loach on a number of films and he asked me to edit a film. Then I went to Australia with my friend Philippe Mora, who was a director. We made this film “Mad Dog Morgan” in Australia, the first film I made, with no knowledge of making films. I was going to produce and edit the film and he was doing the writing and directing. We went there and I didn’t know anything; I couldn’t edit anything.

It was a crazy film with Dennis Hopper in 120 speaking parts. That was my first film and it was the beginning of my traveling and understanding that I really enjoy making films around the world. I liked being in different places and was good at it. I can communicate well — even when I don’t speak the language. I find it very easy to be in the middle of Africa, the middle of anywhere, and just dumbing down with a film crew. I can manage it. I like that challenge and that’s been my life pretty much from then onward.

Q: Speaking of traveling, director Mark Cousins approached you to film your career on the way to go to the Cannes Film Festival. He had a different kind of approach to filming this documentary. Please talk about working with Mr. Cousins.

Jeremy Thomas: Mark Cousins is a very gifted filmmaker and he’s shown it in all his films. He’s very prolific. I’d seen his films and saw his “History of Cinema”— which is a 12 part documentary which explains everything and is very poetic. His other films are incredibly good. I knew who he was because he had been the director of the Edinburgh Festival. He loved the films that I was doing, particularly “Bad Timing,” and I knew who he was.

One day this producer, David Kelly, came and said Cousins would like to make this film and they knew about my road trip to go to Cannes every year by car. I drive there and make a journey of sorts.You’re closer to earth and you see things. You can stop when you want and be in charge of your time. I like that very much. So I said, “OK, you can come — by yourself.”

We did this journey without acknowledging the cameras. He did it all himself. He shot it and then every day he’d call me for an hour talking about things and he used that and he added that to the footage he shot. I didn’t know what he was really doing. I was just talking about playing music in the car, stopping where I wanted to stop, at favorite places.

It was like a freestyle road trip which Mark joined me on and we arrived in Cannes. Miike-san came — we had Miike-san’s film there. Takashi and my Japanese friends were there and we had a nice time in Cannes. I explained a bit about my attitude to it all and he got some secrets out of me, saw me a bit, but not all of me. He’s made lots of films, about four films since he made this film — and never stops. He’s a wonderful documentarian and a complete self-starter. He can do anything, he can make films, just go and shoot in one format after another. He’s a very gifted filmmaker.

Q: What’s really surprising about your career is how you developed your own taste. You have a really incredible and bold taste of choosing the right filmmakers and topics. That’s what’s really fascinating about your career. How did you develop your taste in the first place when you started?

Jeremy Thomas: Well, that’s very difficult. How do I develop my tastes? I suppose I developed my taste and was influenced by my father. He was a soldier in the war and was a successful film director surrounded by movie stars all the time — Bob Hope, Katherine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart and lots more. He made a lot of films — I grew up in that house and just wanted to work in film.

I was a very bad student and the headmaster rang my father up one day and said, “There’s no point in this boy being at school, you take him away. He’s never going to do anything here. He’s hopeless, you know.” So this hopeless boy left and went to work and I was just thinking about movies. I already had my own little films. I wanted to be a film director.

I became a producer in order to direct my own films. I really enjoy mixing up people and cultures and my taste. I’m from the counterculture and I’m proud of it. I like the counterculture. I’m not really into making popular films of our mainstream culture — other people can do that. I’m not interested in looking for the next popular thing. I’m looking for something interesting, maybe something original and maybe controversial because I’m an independent.

I want to make films about something that people can talk about and write about because I can’t afford to publicize my films like a big company. I’m trying to make films with special interests and special people who are your basic audience. I’m dealing with subjects that I hope can accumulate an interest beyond the film star that I need to make them. But the subjects themselves, they’re tasty, like a decent meal. Beyond the narrative, I want the films to have a mighty intellectual side.

It sounds pretentious to talk about it but there’s a thought inside and I use my brain as a hard drive. If I like the filmmaker, I like the texture but I have to feel it. Normally people tell me, “You’re nuts. You can’t do that” That spins me around. They tell me, “You’ll never get that made.” But I want to do it and I’m going to find a way. I managed to find a way after a year, three years, five years, but 20 years; I managed to do it.

At first, I couldn’t find a way to make it. I couldn’t find the resources. I hadn’t seen the way, and the same with “Crash.” It was many years. I had J.G. Ballard’s “High Rise” for many years and hadn’t managed to crack it. I had to find a way to make that film. There’s something in the alchemy that happens. I don’t know. Really. I don’t recommend my message to other people and it’s a different era now anyway. The sort of freedom that I had, I don’t have that anymore. I’m better at what I do now. I know more about producing films than I did 25 and 50 years ago. Of course, today I know a lot more about how to do it. But then it’s more difficult today for me to make the films that I want to make.

Q: Speaking of intellectuals, you’ve worked with such original filmmakers as David Cronenberg, Nagisa Oshima, Bernardo Bertolucci, and so on. What’s your intellectual connection to all those filmmakers?

Jeremy Thomas: I don’t claim to be an intellectual, but I use my intellect a lot to find the right kind of projects. I admire educated people who have money to absorb things around them. I want to learn all I can. I want to see things all the time, to learn, and absorb information from people I respect and who know things that I don’t. I like to work with the people that I find fascinating and whose films I respect. I have worked with first-time filmmakers a few times, but normally I work with filmmakers who understand their work, and I can understand what they’re going to do with the narrative and their style of the film-making.

I understand the sort of film that you’re going to get from different directors, which is a producer’s job. If I put X and Y together, I’m going to get that. I’ve been mixing it up, all these things — actors, writers, musicians, stories and countries. I then try to make it fresh, and a bit original. I’m not interested in trying to go backwards. I want to move forward and find new stories that will stimulate me and an audience. That has something to do with the age of the filmmaker. It’s just following the subjects that are there to make people curious to see my films.

Q: Speaking of music, talk about the casting process for “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.” You hired David Bowie and Ryuichi Sakamoto. Bowie and Sakamoto, they obviously comes from music, and it was interesting casting the two of them together as well. How was that?

Jeremy Thomas: It was amazing. It seemed so easy at the time. I met Oshima the year the show won the Cannes prize. I sat next to him. He then two years later sent me a screenplay of “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence,” which was 220 pages long. I really thought, “Wow, I’m going to work with Oshima.” I went to Tokyo with writer Paul Mayersberg who wrote “The Man Who Fell to Earth” amongst other films. He agreed with my western eyes and brought the screenplay down to a length that we could do, which was very good.

Oshima originally wanted Robert Redford to play this part, but he couldn’t get him. Ok. Then he said, “I want David Bowie.” So he’d already had the idea and obviously [Oshima] had Takeshi [Kitano]. So I arranged for a mutual friend to have dinner with David Bowie in London. In every film he’s so cultivated. I said, “Oshima wants you. He wants you in the movie playing Jack Celliers.” And Bowie said, “I’m in.” Then we cast the Western roles –Jack Thompson and Tom Conti — and [Oshima] cast all the Japanese roles.

He said to me, “You cast the western roles, you understand what they mean. I think it’s different, we think somebody looks like this, but he had faith in me. “You bring the crew from your side.” It was really a co-production with a lot of westerners. You see it on the credits. It’s full of Westerners and Japanese interacting on this island. It was very evocative being in Rarotonga, a place where nobody had probably seen a film camera on that island. He was a really incredible person, very Japanese because he wore a kimono a lot. But he learned, he wanted to learn English and he loved western culture.

He knew Western culture completely. And it was a very great film to make at the time about male love in a prison war camp — then an antidote to the jingoistic normal prison war film. It was a really wonderful film and a great experience making that. That was my first experience in Japan making films and with Japanese friends. I’ve become very close with Japan. I don’t know how many films I’ve made there in my career, probably six films I’ve made in Japan with Japanese filmmakers. I would do more and buy Japanese cinema. I love historical Japanese cinema –they’re beautiful films. I traveled to Japan before I went to Japan. I’ve been to Japan with those filmmakers, like I’ve been to India with Satyajit Ray before I had actually been to India.

Q: Sakamoto’s recent passing was so sad. But you worked with him on “The Last Emperor,” “Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence, “Sheltering Sky” and others as well.

Jeremy Thomas: His son Neo (Sora) directed a film(“Ryuichi Sakamoto / Opus”) of his last performance so my good friend is coming to The New York Film Festival. It’s beautiful — it was in Venice and in New York. [Thomas was executive producer.]

Q: Are you going to come back to New York?

Jeremy Thomas: No, I’m doing other things. But I loved him, his partner Norika (Sora) and Neo (Sora), his son. The group that made that film is very committed and it’s an incredible document. He was a very special man as you know, a professor. We call him a”professor” because he was the real thing. He was one of the best people I’ve known in my life. He was a special person and a genius. I don’t use that word lightly by the way, but he was a genius.

Q: You were there at the Cannes for fishing? What do you mean by that? Can you talk about the experience of going there, finding filmmakers and getting the ideas. You not only actually went there as a producer, but also you’ve also been to Cannes as a jury and the president for the Berlin and Tokyo Film Festival among others.

Jeremy Thomas: Yeah, I did two juries. I did the main jury with incredible filmmakers. Norman Mailer was there in the chair. I did that jury in 1986 or ’87, when I was very young. Then I chaired the jury when they gave the prize. I love film festivals, and can very much go to everyone. I like film festivals because you’re interacting with people who want to go to the movies — they’re my people. Most people go to films for Christmas; it’s not like going to a car show.

Cannes is the mother of all film festivals. It’s like fishing, there’s the best salmon fishing you can find, and maybe you can land a nice fish. I’m very open to ideas and I’m very much a man who’s on the international map. I’m not just open to finding films from my own company. I can make films with people who I can’t even communicate with in their language. And I can use my limited French or Italian. My speech is bad but I use what language I can to communicate with people.

I love meeting new people that I can work with and, in the right circumstances. I’ve caught many films there. I’ve met people there as a film lover and then you’re in the same family, you’re not an enemy. I’m sort of in this secret society with people who are really lifers in the film business. They need to know that I’m a lifer of the film business. I’m always looking for money for films, money into light. There’s no light without the money; a film producer without money is a hopeless creature, right? You have to have money to buy lunch for your director. You’re going to have to be able to pay for a book, a script — maybe you’ll pay for it wholesale — but it’s hard to be a producer without any resources.

Q: You made films with David Cronenberg but with the movie “Crash,” it had a lot of bad press when it came out. Talk about the response towards the film back then, and how it affected you because the film really made Cronenberg — someone who is really impactful. Did you understand that when you made the film that it was going to have such a reaction and overreaction?

Jeremy Thomas: It was mad, it was stupid. It was sensationalistic and crazy, the press conference and the reaction. Jim [J.G.] Ballard, who was at the press conference, was extremely happy and we were all happy that people were shouting and screaming at us, hundreds of them. But in the right way. They were really shocked and offended but we didn’t know what was going to happen. We had no idea.

I had a bad time in England because they kept on showing photographs and my children were abused at school and all that sort of thing. Then one day, I was at a pub on the Isle of Man with Philip Noyce looking for locations for a film we never made. But, then, behind us were these women and a man talking and I heard “Crash” and they said they should be strung out. These people make films like that. They wanted to kill us, that we should be hanged. It touched a nerve in England and it’s still banned in London. The film is never going to be shown in the cinema there. That’s bad.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.