Exclusive Interview with Actor Cliff Curtis and Director Tearepa Kahi

Q: Cliff, you’re of Maori descent. You played the guy from Te Urewera in this film. Now you’re in the Avatar series. You seem really connected to the story of indigenous people. What attracted you to this script that made you decide to be in this film?

CC: Many, many things. I remember very clearly the actual events of 2007 when the police publicly enacted the rights against this tribe of Tūhoe and specifically Tame Iti, who I had known for some years before as an artist of repute, a restauranteur, honey collector, dancer, painter, and as a deejay. All of a sudden, the government decided to profile him as a domestic terrorist.

[I go] “Uh-oh.” I didn’t think at the time, “Oh let’s make a movie about it.” It’s “Oh no. The New Zealand government is making a huge mistake and there will be an apology someday soon.” And that’s exactly what happened.

Q: Tearepa, you cast Tame Iti as himself in the film.

How did you convince him to be in it?

TK: We have a long-term relationship. Cliff has been a huge supporter; he’s like my older brother. I’ve walked forward in his wake and with his support always.

We also have a personal relationship with Tame Iti. For me, in the vision of the film, there was never a case where we considered another actor back home to be able to play Tame Iti. He is one of one. And because of that one-of-oneness, he also has a mnemonic power.

Being able to construct the campsite, a court scene, a honey collecting scene — all of the things that Tame does in his natural, everyday life, was great to use for this story and the scene construction. I’ve spent a long time with Tame so I wasn’t stealing. I was always taking notes from what he was saying, it’s his language.

So when I presented the script back to him, he wasn’t reading someone’s idea of him from a distance. He said to me, “Hey, these are my words. This is how I speak.” I said, “That’s right. Papa, you can play this role.” He said, “I can play this role.” He said it again and again to me in a 30-minute conversation — about a hundred times: “I’m Pa, I can do this!” That’s how Tame came in — just giving him confidence and trust.

And then, he works alongside Cliff, and leads another cast of people who weren’t from Tūhoe; that’s just what Tame does as well. He’s a very generous man.

Q: Cliff, what was it like working with him? CC: It was great fun working with him. Of course, there’s the weight and importance of the story that really matters to us and to him. There’s a weight of responsibility. But it was fun to be in his neighborhood, in his valley, with his people — his sons, aunties, and cousins. I really enjoyed working with him as an artist. I’ve known him as an artist, but to work with him as a fellow artist together on a story that mattered to him was a real pleasure. I really enjoyed it.

Q: The location, Te Urewera, is mostly forest, and sparsely populated. It’s a very beautiful place, but rugged hill country. What were the challenges of shooting there? How did you capture the atmosphere?

TK: You don’t get to enter into Tūhoe without an invitation. It’s a very remote and ancient area. It’s pristine — the water, the forest, and the land is pristine. Culturally speaking, it’s very intact. A film hasn’t been shot there for a very, very long time.

So coming into Tame’s neighborhood, as Cliff said, on [Tame’s] invitation with full support was a huge honor and a huge undertaking in terms of how we captured it.

There are so many signs… We call them signs. When you see the mist in the valley, it’s a sign to say that you’re welcome, so the invitation is legit. We were able to operate there, not as a film crew, but with full support of the community. This was the first time that a lot of people in our crew had been there.

But I had been there working with Tame for over three years, walking the land with him, looking for the right spots. Because of his guidance and support of us, we were able to faithfully exhibit and depict the depth of the valley, its contours as well as the human contours which are shaped by the physical space.

Q: The New Zealand government apologized to Tame Iti, and admitted their actions set relations back decades. There are a lot of police cars and weapons in this film. How do the New Zealand police stand on this film?

TK: It’s a great question. They asked us — they “requested” us — to use the disclaimer which starts the film. They have apologized to Tame and the Tūhoe people. But it’s still a big undertaking on their behalf — not to allow so much, because the artists, the community and Tame needed to vent outright to speak truth to their story.

That’s not what we were asking for. We never put a proposal to them saying please can we tell this story. That’s not what happened. But in order to use the coat of arms and the uniforms, they did need to sign off. And because it’s Tame, and time has passed, and because of the participation and blessing, I think they had no choice but to [let it happen]. I’m not sure.

Q: In 1916, the New Zealand government raided the people of Tūhoe and their prophet Rua Kenana. Since then, the Tūhoe people have been faced with unfair treatment. So what happened in 2007 is certainly believable. How did you collaborate on the script with writer Jason Nathan to make it more true to the event as well as cinematically effective?

TK: The whole motivation behind this script and the artistic direction, is to ensure that this day never happens to Tūhoe again. This is a preventive protest, to ensure the ongoing protection of our people.

There was much more to draw on than the events of a single day. When we put the historical contextual scope and interrogated it and looked at it, with research and with time, and with retrospective power, we landed here. This is not about one day, it’s about ensuring the ongoing protection of our people. We’re ensuring that it never repeats again.

Q: The Toronto international Film festival included the film “We are Still Here” that’s also related to the indigenous people in New Zealand. What does it mean to you having both culturally influential films out in festivals?

TK: Speaking personally, and also as a Maori storyteller from Mao Tearoa, this is in many ways a very special landmark moment. [It’s] a significant time marker, that we can be here depicting stories from deep within our bellies, from deep within our cultural memory, and now have the opportunity to share it with an international audience. Long may it continue and grow.

CC: Well, it’s not my first time, actually. I came here with “Whale Rider” and also a movie called “The Dark Horse,” which is a story drawn from our indigenous heritage. What’s unique about this particular film or “We Are Still Here” is that these films are owned by us now. That’s an important distinction for us.

We are going to, as storytellers, go into territories that are going to occur to us in a way that shows our sense of what is unique to us. We have a uniqueness and yet, we are comfortable with different things. People from outside our community can interpret things in a way that are going to make sense to audiences, but they’re not going to be comfortable or even knowledgeable in areas of who we are as we are. So it’s important to us, an important distinction, that these films that are written, directed and produced and owned by us, and that we have the support of our government to do this, as well.

It’s an important distinction, and long may it continue. It’s our life’s work. It’s something that was laid out by others before us. Merata Mita, [a pioneering filmmaker], came to Canada many times. We did a documentary series that we worked on together about her. We’re standing on the shoulders and works of others that have come before us.

So what is indigenous storytelling? One definition is of course not unique to us; other cultures have this value. But what defines it for me are stories that honor our history, heritage, ancestors, and that stands the test of time for our children and grandchildren. That’s not a superficial thing — it’s not just about making a product for the marketplace. It’s about making something precious that we want to hand forward to future generations.

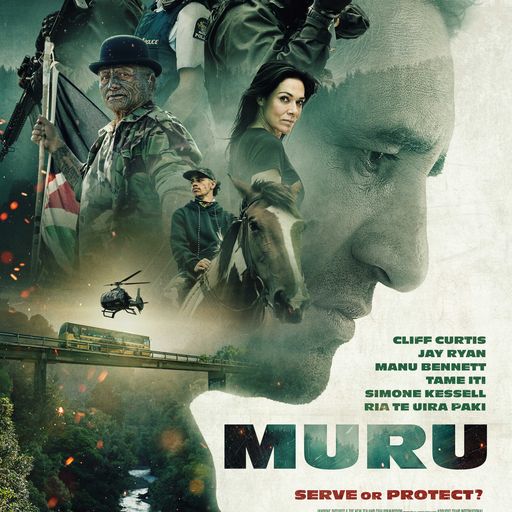

Here’s the trailer of the film.