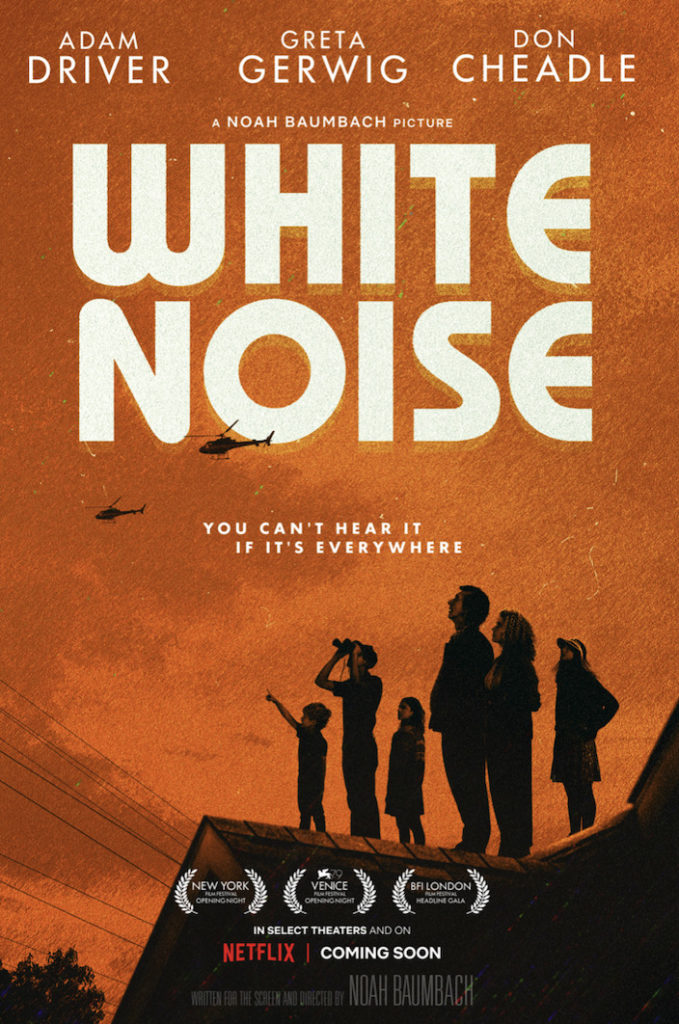

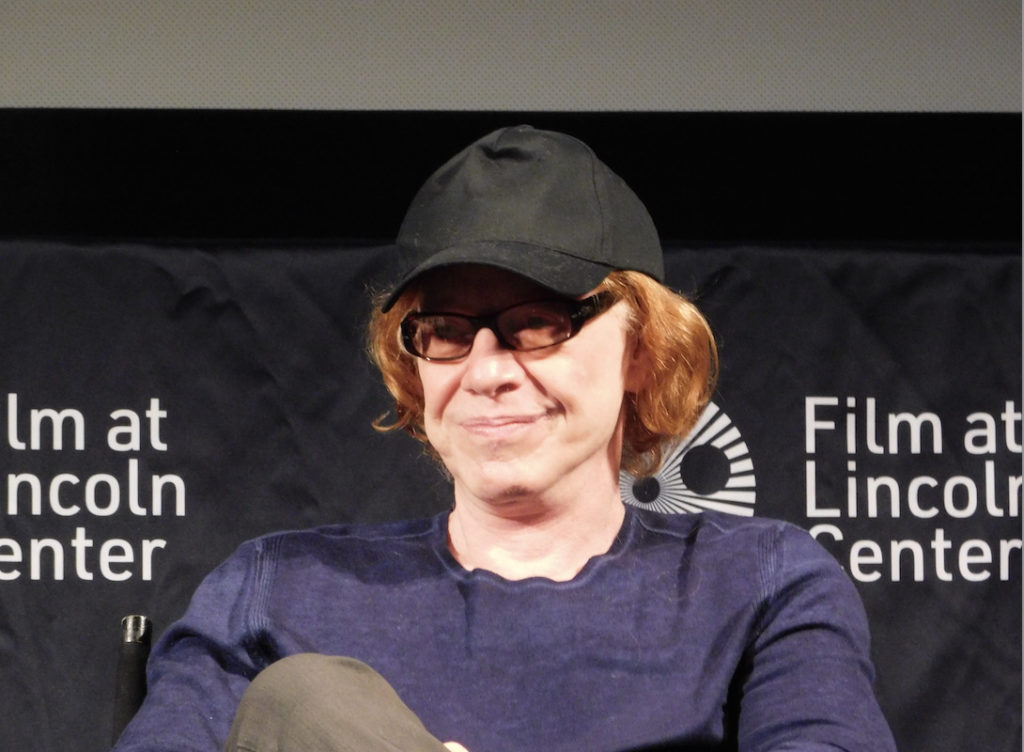

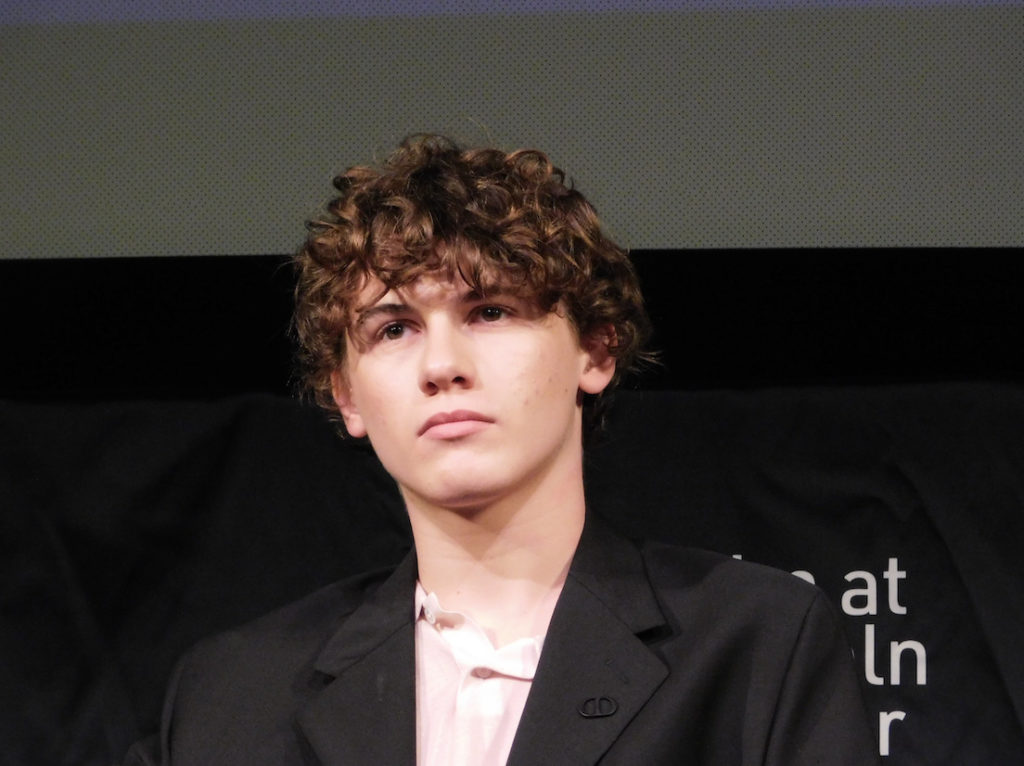

Press conference with director Noah Baumbach, cast members Greta Gerwig, Raffey Cassidy, May Nivola, Sam Nivola, composer Danny Elfman, and songwriter James Murphy

Q: Noah, you’re known as a writer-director. You wrote or co-write all your films, it’s always been original material. This is your first adaptation — not just any old adaptation, but a book, “White Noise” by Don Delillo. It’s also a book that’s been called “un-filmable.” What was it about “White Noise” that suggested itself to you as a film? What was it about the book that made you want to see it as a film?

NB: I think a lot of it was the timing of it because the book had occupied a huge part of my consciousness from having read it when I was a teenager. I hadn’t read a Don Delillo book for years. I casually started reading it again at the end of 2019, beginning of 2020. I found myself finishing it as the pandemic arrived. It was also the first time in my career up to this point that I didn’t have anything that I necessarily felt alive enough that I wanted to do. So I set out to do it as an exercise because, on finishing the book, I felt like this represents how I feel right now. It would have been true with or without the pandemic but that certainly put a finer point on it. I set out to do it almost to occupy my mind. Then I started showing pages to Greta and she was encouraging. I got deeper into it and I felt, “Well, let’s try this.”

Q: Did it feel like a different process for you, working with Delillo’s text and language? There’s something about the prose of the book and dialogue. Looking at the reviews of the book when it came out, especially the review by Saul Urich — who wrote “The Warriors” — he commented specifically on the dialogue. He said that there was something heightened about it, “On close examination, you realize that no one talks like this and yet everyone does.”

NB: I think that’s a great way to put it. It’s different, because dialogue is a big part of my scripts and it’s often how I find the movie. I often write dialogue to discover the characters and story The rhythms of it is something that I pay close attention to when I’m shooting, and the actors. So it was a new thing using Delillo’s dialogue, but it felt very familiar to me. In some ways, it wasn’t different because my original dialogue is also very stylized. But when we make the movies, part of the design of it is that it feels naturalistic. But, if you break it down, it’s almost the opposite of what you say about Delillo’s words. It’s clearly artificial but if you have these actors do it, it can create its own recognizability, its own naturalism, in this heightened world. I felt like I had to figure out a way to create a kind of cinematic analog to what Delillo did in a literary way. I wanted the movie to have its own version of this elevated tone — this real-but-not-real feeling that I had — and that I think most people have when they read a book.

Q: Let’s hear the actors talk about this process of turning these characters that, in the book, are a bit abstract, but [have to become] flesh and blood characters. It’s quite faithful that you use a lot of Delillo’s dialogue in your screenplay. Greta, what do you think about this process?

GG: The relationship a reader has to a book is very different than, obviously, an actor has to text. But even though there is something heightened and surreal, and sort of floating above the Earth about the entire world he builds, which feels adjacent to our world but is not exactly our world. There’s also something about it that very much makes you feel like you want to speak the words out loud while you’re reading it. While Noah was reading it, he kept saying, “Listen to this” and then he’d read it out loud. He had me re-read it and then I was like, “Wait, wait, no, listen to this.” There’s something about this book, too, that everybody’s got their favorite lines and favorite parts and their favorite thing they want to tell you about it. They’re sort of mad if you didn’t use the whole thing. And you’re like, “Well, it’s a film, that’s a book. It would be impossible to fit every smart, amazing thing Delillo wrote into [the movie] because it’s on every page you’re turning. I write in books, underlining everything.

But the question of how do you make that psychologically real, it’s tricky. It’s not quite Brechtian. You have to inhabit it as a person, but it’s also operating at a different level. What was really helpful in that was getting to rehearse with all of us. We got a month of rehearsal, which is extremely rare. So me, Adam, the kids, Don — we all got to be together working on these scenes in the location. As soon as it’s embodied, it stops being esoteric and so heady. It just starts being lived in.

Q: Noah, in casting this, how did you put together this family, this cradle of misinformation?

NB: Greta cast herself in it while I was writing it. And I agreed right away. I’ve worked with Adam a lot and had been thinking already, talking to him about maybe doing something. I sent him the book, and I said, “See if this feels like something you could do or would want to do.” He got very excited about it. While working on it, I knew Greta and Adam, and that was compelling to me because generally in my films, I work with actors who know what they’re feeling or what they’re thinking about. I want them to play the parts generally as close to themselves as they can. In this case, their performances felt like the right thing. I felt like they should be, “you but not you.” Casting someone like Adam maybe you wouldn’t think of right away. But I felt that was an exciting thing.

And Greta with the hair, the important hair. After that, I knew the kids were going to be such a big part of it, so that was just auditioning. I worked with Doug Abel, the casting director who I’ve worked with for years. We’ve cast a lot of kids over the years, but it’s always daunting. I got very lucky, they were wonderful. Two of them actually lived together or were related, which was a happy accident. Raffi auditioned from England and was fantastic, and I’d seen him in a couple of things.

It becomes then a process where you had them read and read and read, and read with different people. And this was the pandemic, so most of it was all over Zoom, really. That’s always something: if you can’t find the kids, you know you can’t make the movie, but you don’t want to admit that while you’re doing it.

Q: Raffey, Greta was talking about the rehearsal period that was important for the shoot. There are these chaotic family scenes, filled with lots of crosstalk, especially in the kitchen and car. What was your experience working with those scenes?

RC: We all had such a great experience with the rehearsal process even before we did a month of rehearsing together. Me, Sam and May worked with Noah going through all the lines together and being so comfortable. Then we went our separate ways and sat on those lines during it. And when it came to rehearsing, I so vividly remember doing the kitchen scene, which almost became like a dance. Everyone knew their positions, it was rehearsed, and then when it actually came to the day, we knew what we were doing.

SN: We also had an awesome choreographer named David Newman, who really made it all feel like a dance, in a certain sense, which I think worked perfectly. Every little spin was carefully thought out. It made it a lot easier to think about what you were trying to do in your head. You could be settled in your external environment.

MN: Like what Greta was saying [about] the rehearsal, [it was] like being with your new family and having that experience with them and rehearse with them for so long. It’s like you get to love them and know them, and it really feels like your actual family. I think with Sam and Raffey — I’ve known him all my life — but I got closer with him than I’ve ever been. So that was really nice. And with Raffey — she’s lovely to be with and be able to have that experience. It made us closer and better actors when we were playing the roles of siblings.

NB: My suggestion to them was that they were like a radio that was turned on at the beginning of the movie and then they just talked the whole movie. Whether we see them or not, they’re still talking, and then when it’s over [they] turn it off.

Q: And this is the first time you’re working with Danny Elfman?

NB: It is, yeah. But not the last.

Q: The score plays a big role in how the film orchestrates its tonal shifts. What did you have in mind, what reference point, and say something about your collaboration?

DE: Well, from my side, it was really exciting because there’s no genre in this film and to have a film that has no genre tells you that the type of music you should write is [for] pure joy. Of course, working with Noah, everything was fun and pleasurable. He has ideas, and nothing’s more enjoyable for me than just trying things. We first met by Zoom, and he was already like, “Can you start on some music right away?” I said, “Well, I’m in the middle of this Doctor Strange movie — but okay.” I just wrote some stuff blind and sent it to him. The next thing I know, he’s cutting my music into the movie in ways that I hadn’t even thought of. Then we got more and more into trying things.

I’ve worked on a hundred and 10 films now, I think, and this definitely is one of the most enjoyable. There’s no moment in the film that are dropping into a scene in the film that wasn’t a pleasure to work on. There wasn’t these struggle sessions of “Omigod, how am I going to get through this section?” The chemistry of everybody is so wonderful that no matter where I dropped in on the film, it was pleasureful. Noah would feed me ideas, and we would play it up and bounce things, “try this” or “try something completely different.” What’s more enjoyable than that? I mean, for me. It may have been horrible for Noah.

NB: No, it was fantastic. Even our first conversation — I would talk about the movie and what I thought the themes were — even non-musical themes. I thought in broad terms that the first section was, in a sense, the systems and strategies that we’ve created for ourselves to keep death at bay or to keep this illusion of immortality going. The second section is, “here comes death to our door” and it’s real. But we don’t know how to acknowledge its reality because we only know it from movies, and from a distance.

And the third section is, “Okay, now you’ve seen it, what are you going to do?” Do you go back to the same strategies? Can you? Can you do those things? Hold up under this with this new knowledge? I would basically say something like this to Danny, and then I would hear silence. Then Danny would come back on the phone and say “I’m sorry, I just had an idea and I didn’t want to lose it. So I went and started writing down some stuff and recording a little bit of music while you were talking.”

Then I would repeat myself. But he was amazing. He was so alive with ideas all the time and that was the whole process. I actually went to his studio in L.A., and even though we were still editing — the editor Matt Hanum and I — we basically set up shop without asking him, while he was there, and he would come, record and play around with things. Then he would come and knock on the glass. I would come out and we’d listen, talk, and we’d go back. His music would influence the cut, the cut would influence the music. It was really an ideal, wonderful situation.

DE: It’s the first time, for me, working like that too, and I loved it. Everything was instant, the response was instant. I guess that’s the kind of thing that maybe an actor has that experience, going through dialogue with the director. But as a composer, you don’t get that kind of quick, “try something, play it, try something else.” So it was new for me, too, but it was great. I hope we do it again sometime.

Q: There is a Frances Ha moment, and the Sondheim songs and “Marriage Story.” Can you say a bit about your decision to end this way? This is something that has no corollary in the book. You’re just devising this musical fantasia to close the film. Can you talk about working with James?

NB: Yeah, in the writing of it, when I arrived at the end, I think. It’s such a literate book and literate script and movie because of the source material. I felt that the movie had given me permission to do something that felt non-verbal, a kind of pure cinema, and be something that was visceral, pleasurable and exciting — it’s a way to celebrate both life and death at the same time.

I had worked with the choreographer David Newman — who, as Sam said, worked with us throughout the whole movie. He worked on “Marriage Story” with me as well. So I went to him, and then to James [Murphy]. James had lived in the ‘80s, and made movies in the ‘80s. If I had heard any of the music he made in the ‘80s, I was like basically, “Why don’t you write the song that you would have written then?” I worked with him before and we’d become quite good friends since “Greenberg” when we first worked together. So I had this idea, why don’t you write a joyous song about death?

Q: You talked about looking for cinematic analogs to Delillo’s language. The idea of “white noise” comes across differently in cinema than on the page. Can you speak more broadly about that, about cinematic expressions of the idea of white noise?

NB: I thought a lot about it. In a sense, a lot of what is described in the book is visual, oral and sensorial. Those are things a movie can do that a book can’t do. So I thought, why is this un-filmable? This is really easy to do. I thought a lot about [how] this goes to the way we use dialogue, so we miked everybody. I thought about Robert Altman movies and this is one influence in that way of miking everybody and having everybody speak at once. But also playing with focus so that when the audience is watching, they can sit back and let it all just be noise, or they can go in and we’re helping them out but they’ll start hearing what they need to hear if they want.

And we shot anamorphic — 35 millimeter anamorphic, which, of course, creates a very specific frame and aspect ratio so that you can see many things at once. If you do a closeup of a face, it’s very powerful. But you can also pack the frame and do things right and left. There’s so much you can do.

I also love the movement [with] anamorphic. If you move when you’re moving the camera anamorphically, you can pick things up in the corner, and a person can come in this way, but they’re picked up much earlier than they would be normally. It’s the first time I’ve worked that way, and I really enjoyed it but it’s challenging too.

I also thought a lot about visual white noise in a way, of how the supermarket is an obvious example of that and how it’s both. If you see it from above as we do, it’s color, and just a mass of information in color, but if you’re down in the aisle and you’re looking for that very specific thing or reading the ingredients on a package, you’re all the way down in that moment. We did that throughout the movie, even in ways like in the barracks.

I was influenced by the scene in “Notorious” — the Alfred Hitchcock movie — where it’s a wide shot of a party and an establishing shot, but the camera goes all the way down, down, down, down, to Ingrid Bergman holding [something]. It goes down to her hand, and becomes a closeup of a key in her hand. It’s so much story in one shot. But it also [goes from] the broad to the specific.

I thought, well of course, this movie is about that in so many different ways. You have the country, the individuals in the country, this family in the country — it keeps going down. So that shot at the barracks is a wide shot of people going to bed and things, and it goes down, and by the end of it, we’re at the pill in Babette’s hand. That was a guiding principle and those were cinematic ideas I had that were influenced by, not specific scenes necessarily in the book, but concepts and ideas that Delillo put out there.

Q: The costumes also look both real and unreal. You worked with the wonderful Anne Roth. Could you talk about that?

NB: I’ve worked with Ann a few times, an amazing friend, and collaborator. I love working with Ann. Ann understood immediately, exactly, that real and unreal thing. With production designer Jess Goncher, it was the same thing. We talked about an authenticity to the period, but not any specific year or that it was to keep things both with color and style, just to keep everybody slightly above the ground.

Ann is an amazing costume designer. She is a collaborator in the way that she gives you everything — she helps me direct. Actors will go in for fittings and come out suddenly knowing so much more about who they are. I’ll say something in the line of direction and an actor will say to me, “Well, Ann thought maybe…” and [I’ll go] “Well, Ann knows best, let’s just go with what Ann says.” No but, I feel lucky to have worked with her.

Q: How did you conceive the ending, the dance number in the supermarket? The music is fantastic. But the scene is not in the novel.

NB: When I’m directing movies, I’m always interested in how often the story, the mood, or however the movie progresses, that it gives you permission to do something that was unavailable to you at an earlier point in the movie. I’m always trying to be aware of that as a director and writer. In “Marriage Story,” when Adam sings “Being Alive,” that’s something the character couldn’t have done earlier. It’s something the movie couldn’t have done earlier. The camera moves differently in the moment. It’s simple to push it. But it moves differently in that moment than it moves at any other point in the movie.

I felt similarly about this, and this movie has so many things going on in it that I felt like we were given permission all the time to try something new to do, to move to another place. It has so many genre elements baked into it, too. I always wanted to be aware of what was available to me genre-wise. Him going to the motel, that we’re in a kind of ‘80s noir movie now. It’s something Alan Parker or Adrian Lyne would have done brilliantly. I thought well, maybe we can also be a musical, and the movie has allowed us that — that was a big part of it. Part of it, too, is intuition in the moment — a lot of it is — and then later you define it. But that’s how I would define it now.

Q: How did you choose which cultural parodies from the book to include and not include?

NB: Joel and Ethan Coen have a great quote when asked how they adapt other material. Joel says, “I hold the book open and Ethan types.” I think in the beginning, when you are adapting a book, everything is possible and you’re going to use all of it.

With this book in particular, as I’d go through it, I’d be like, “I’ve got to include that, and we have to do that.” There are many great moments in the book. When I would go back to the book sometimes I’d be like, “Oh, wow, yeah, I could have used that” or “well, no” or “I don’t know.” I must have had a reason at the time. There are things I shot that I ended up taking out as well. The movie becomes its own thing, and it has different needs and wants than a novel does, obviously. It’s not even like, “Oh, I’m not going to use that, but I’m going to use that.” It became what is going to help me tell the story as I see the story in the movie, and I followed that.

Q: Was it difficult to shoot and score the action-oriented scenes?

NB: There were definitely more people in this movie than in many of my movies combined. There are things that you want to be attuned to, but it’s really the storytelling. It’s shooting the family in the kitchen, or in evacuating the Boy Scout camp. Essentially, you’re following similar principles and guidelines, which is to be true to the scene, get them from A to B, and understand how you’re going to cut it later so that you have what you feel you need.

It didn’t feel different to me. I’m working with stunts in a way that I haven’t before. We also did everything practically as much as we could. So the train crash, the evacuation, the creek, the car in the creek — we did those things. Even the cloud has a lot of cloud tank stuff in it, so it’s got real cloud in it. Partly it’s because I wanted to be true to the period in a certain way, but also because I find that way of doing it both fun and challenging. But from the aesthetic perspective, I find it more pleasing. I’m more afraid looking at the Creature from the Black Lagoon than I am of a digital monster. I don’t know if that’s a common thing.

Q: How did your own fear of death influence your character, your direction, your music, if that’s something you suffer from?

DE: The first thing Noah said to me when we met on the phone was, “This movie is made for you, Danny. It’s all about death and fear of death.” And he was right. It was like, “Omigod, that’s so up my alley.” So he had me nailed with that line right there. It’s all I needed to know.

Q: No one else is afraid of death? How lovely.

GG: I’m super-scared of it. There’s so much heightened-ness in the movie. And the heightened-ness of the book. It’s so smart that to explain it, you end up sounding like a stoned teenager, because you’re like, “No no no, it’s doing two things.” It chronicles all the ways we distract ourselves. And in that, it allows us to delight in it as well. So you are delighted by the distractions that have already been given to you, but he’s pointing out that there’s multiple mirrors happening. In the same way, academia flattens everything.

Commercials flatten everything. News, media — it’s like you have a commercial for M&Ms right after you’ve got plane crash footage, and that’s the same value and it comes through as the same thing. You’ve got Elvis and Hitler and it’s all the same. And there’s a way in which we welcome the flattening to our own psyches because we don’t want to know that we’re on a trajectory that goes in one direction [gestures down]. So we think, “Oh, that’s good. Maybe we’re all flat.” To play the parts is to steep yourself in distraction and let the fear poke through.

NB: I think we want to look and feel that way, and it can be beautiful. Even if we know what the supermarket essentially is designed to do to us and for us, it also looks amazing, and it’s beautiful. I wanted to celebrate it as well.

GG: Also the way we were talking about the dance and saying we wanted to make something that was a celebration of life and death. We were talking about it like, “Well, that’s the same thing. If you’re celebrating all that is, then you’re celebrating all that will end. You inherently are, because it’s going to. Everything about having a heightened choreographed dance in the supermarket — as if what you do in the supermarket anyway isn’t a codified dance that we’ve all agreed on the rules. We’re already dancing. It’s just that you can see that this is a dance, and the rest of the time we’re pretending it’s just behavior.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.

[…] a movie based on a book. “I felt like this represents how I feel right now,” Baumbach said during a press conference ahead of the film’s release. “It would have been true with or without the pandemic but […]

Thats what i was finding since a week and it is very interesting article.