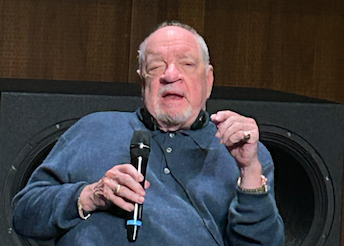

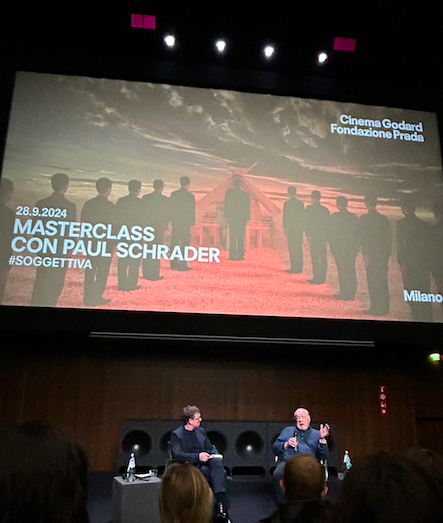

The Prada Foundation hosted — within its Cinema Godard — a Masterclass with the accomplished filmmaker Paul Schrader. During this occasion, the multi-hyphenate cineaste retraced his experience as film critic, screenwriter and director.

Italy had previously homaged Schrader through the years, with Masterclasses and accolades at the Museum of Cinema in Turin, at the Lucca Film Festival and the Laceno d’Oro in Avellino. Recently, the occasion came also for the city of Milan, through a compelling conversation moderated by Paolo Moretti, curator of the cinematic selection at the Prada Foundation.

A fifty year career was revived by embarking upon a trip down memory lane, starting from Schrader’s hometown: Grand Rapids in Michigan. The filmmaker recalled the very Dutch population that influenced his upbringing.

Cinema arrived in the filmmaker’s life during the Sixties, through the fascination for European cineastes such as Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson. But the moment he actively got engaged with the realm of the silver screen was through a serendipitous encounter with the iconic female film critic Pauline Kael. Schrader recalls this meeting vividly: “I was a college student, and had enrolled on a summer course at Columbia Film School. My friend Paul Warshow noticed I was reading Pauline’s book, ‘Kiss Kiss Bang Bang,’ and he knew her through his father, who had been a film critic for the Nation. He asked me if I wanted to meet her and we went to her apartment for dinner. She was a great arguer and we spoke for hours, she encouraged me to be a film critic and I somehow became her protege. She helped me get accepted at UCLA Film School and get a job at the Los Angeles Free Press.”

Thus began the cinephile journey of the man who would eventually switch from critiquing the movies made by others, to writing scripts for directors, and ultimately directing himself. During his apprenticeship phase he never considered becoming a filmmaker until he saw the film Pickpocket. That marked his epiphany in terms of believing he could write not only about the screen, but for the screen. Later on, Scharder wrote the legendary script for Taxi Driver. Brian De Palma read it and told him he couldn’t direct it, but would introduce him to someone he thought was the right fit…we now all know who that director was: Martin Scorsese. Schrader reminisces this episode contemplatively: “Who knows about the zeitgeist, sometimes you just hit it.”

The success of the film was not only determined by the fluky encounter, but also by the circumstances that inspired Schrader’s creative process. For Taxi Driver the screenwriter grasped inspiration from his life, that at that point was discombobulated as much as the character’s. Schrader had ended a romance, he was jobless, without a home and was living most of his time in his car. The narrative that started building up in his head was shaped in a form of metaphor. It spilled off his quill onto paper very quickly: in only a couple of weeks. Soon after, whilst Paul Schrader’s brother had gone to Kyoto as a missionary for the church, he started getting absorbed in the atmospheres that would lead him to write the screenplays for Yakuza and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters.

Schrader’s bond with Martin Scorsese did not end with one film, since he wrote three more pictures that would be directed by the Italian-American cineaste: Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ, Bringing Out the Dead. For the latter, Schrader believes to this day that Scorsese miscast Nicholas Cage, who was too old for the role. He would have rather had an actor who was 23 years old, like the character, and was therefore inexperienced towards the events that fell upon him. But this is not the reason why their collaboration ended. Schrader stopped working with Scorsese when he realised he was ready to direct. However, as avid cinephiles, they continue their ardent conversations about the history of moving pictures. In fact, the friendship between the two still thrives. Schrader found an amusing way to describe the similarities and differences between them. “We are similar because we are both short and asthmatic. But we are also different: Marty is Italian and from the Big City, I’m Dutch and from the countryside,” he said.

During the Masterclass Schrader further discussed his process in shaping films. Adaptations are the most challenging scripts for Schrader, as he jokingly explained: “Some books just open their legs for you and let you adapt them, others resist you.” Furthermore, his screenplays get transformed according to the cast he works with. When he goes through rehearsals he realises scenes have to be re-written to fit the actors, as opposed to how he initially penned them to lure them in the project. The crucial aspect is timing: “Don’t write until you know,” says Schrader, firmly believing that each scene does not come alive from scratch, but should already be in the screenwriter’s mind as he concludes the previous one. Whilst discussing this process one can perceive the method of a mathematician who leaves nothing to chance. He even predicted that his upcoming script — about a professor of philosophy [The Basics Of Philosophy] — will be 78½ pages long.

The time we live in also influences the work of a screenwriter, who has to compromise with the receptivity of the current society. This aspect was examined through a question from a spectator that allowed to unveil a hidden trait about a film Schrader not only wrote but also directed: American Gigolò. The movie had a strong gay subtext, since the time of filming required a more conservative approach on these issues, but had it been shot today “I would have put the gay traits in the text,” said Schrader. One can’t help but wonder what to expect in Oh Canada!, which reunites Schrader and Richard Gere after 40 years.

Music has also been a determining factor in Schrader’s filmography, through his collaboration with composers such as Giorgio Moroder. The score has the power to enhance not only the action but the inner conflicts of the film characters, which in Schrader’s case have a compelling charm for the way they embody contradictions. This is the human trait par excellence that he brilliantly conveys on screen and that keeps him motivated in his storytelling, as he describes: “There are people who do the right thing for the wrong reasons; or who do the wrong thing for the right reasons; or who don’t know what to do…they are the ones that make a good movie character.”

The digital revolution was another topic that Schrader discussed passionately, by saying how he continued making films thanks to the technological evolution that has allowed to make films in less time and with a more contained budget, as opposed to when he began. It has also granted Schrader the liberty to shoot venturesome projects such as The Canyons, casting Lindsay Lohan at a time when productions would not, as well as pornographic actor James Dean.

The American filmmaker also discussed the way cinematic taste has changed through the years. Paul Schrader believes that his generation took cinema very seriously, whereas now it’s less about going to the movie theatre to see a picture that gives room to reflection, but rather to see one that will leave the audience entertained.

To go full circle with the starting point of the Masterclass, Pauline Kael wrote an article in the early Seventies in which she argued that a new generation of young and promising directors was being formed in Hollywood. The ones she referred to as ‘The Movie Brats’ were Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola. Surely Paul Schrader belongs to this New Hollywood category, but since time has rolled by he jocularly concluded: “New Hollywood is now Old Hollywood, because we’ re old. Film students look at me now, the way I looked at D.W. Griffith, and we are talking about a silent film director!” Surely those cineastes had a knack for cinema and Paul Schrader joins them in having elevated the prestige of the seventh art.