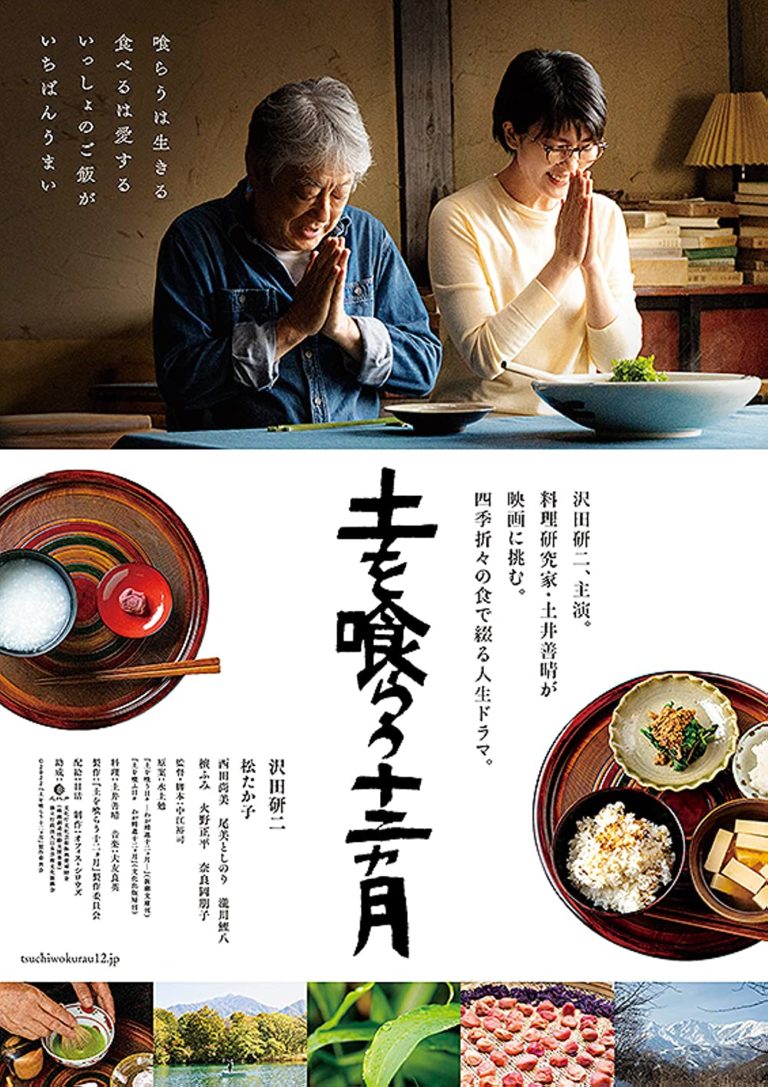

Nothing beats eating with a person you like. This feeling is conveyed by Yûji Nakae in his The Zen Diary, part of the ACA Cinema Project Series. The filmmaker from Okinawa adapts for the silver screen the 1978 nonfiction book by the late author Tsutomu Mizukami.

The picture is a gastronomically spiritual journey through the seasons. These are more nuanced than the Western categorisation of the Gregorian calendar, that divides them into spring, summer, autumn and winter. The Eastern sequence strictly follows the life cycle of the Earth, as every change of the season is accompanied by a Naturopathic precept.

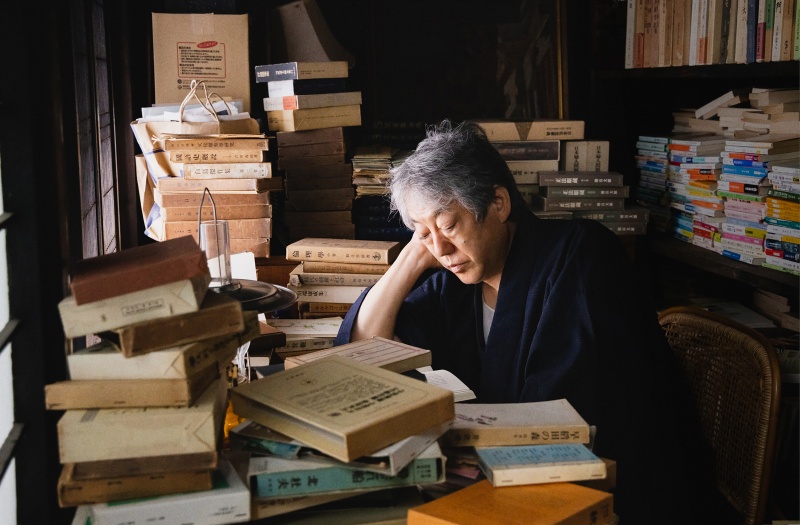

The opening theme by Yoshihide Otomo, with its avantgarde-jazz-experimental-rock twist provides an energetic beginning that suddenly gets swept up by the pensive minimalism of zen and its immersion with nature. It is the time of Risshun (February), ‘Year Beginning’, when we are introduced to writer Tsutomu (Kenji Sawada) who lives alone in cabin in the mountains of Nagano. He collects fruits and mushroom in the wilderness and also raises vegetables in a field. Tsutomu spends his days cooking meals with these nature ingredients. Persimmons, matcha, taros, hot sake are the first elements we see him transform into succulent dishes.

This activity allows Tsutomu to feel the flow of the seasons while he writes his book. His only company is his faithful dog Prickly-ash. From time to time he is visited by his editor Machiko (Takako Matsu) who tries his culinary creations, and for whom he has an unrequited liking. Tsutomu’s heart also beats for his wife Yaeko, who died thirteen years ago and is still unable to bury her ashes. He still meets with his mother-in-law Chie and brother-in-law with whom he has kept a good relationship.

The food that has been brought to the screen by chef Yoshiharu Doi intertwines poetically with the narrative and sensations that are conveyed through the smell and taste of the Earth. Eating becomes a phenomenological experience where the senses intermingle with consciousness and Mother Nature.

Thus we traverse Keichitsu (March), when ‘The Underground Awakes’, allowing us to explore what mountain life in Suge village looks like. Through the use of voice overs, Tsutomu narrates his youth as a novice monk at a Zen monastery in Kyoto. He began at nine years old and that is where he learnt how to cook Zen food. He then ran away at thirteen because he felt unqualified. Meanwhile these remembrances are chronicled as Tsutomu faithfully follows the receipts of the book Instructions To The Cook by Master Dogen. As he immerses himself in the process, Tsutomu remembers how he learnt at the monastery to ask the vegetable field what you should cook.

Gourmandising with the seasons is like eating the Earth. Nature explodes in its most vibrant vitality in Semi (April), when ‘Spring Is Enjoyed By All’. We admire nature at its best, flowers blooming, birds fluttering and chirping, fish sprouting in rivers. As Tsutomu walks in the hills, it’s time for the angelica-tree shoots, rice and soybean paste with wild vegetables.

The resourcefulness of nature starts to head towards a more existential route, that explains the interconnectedness between everything on our planet and the way we enter and exit this world. To introduce this topic in the filmic stream-of-consciousness Tsutomu quotes a poem by the wandering monk Saigyo, whose written desire was fulfilled: “My wish is to die in spring under the flowers when it’s the second full moon of the year.”

Movement is life and hunger improves the taste of food is what the Nipponic gourmet explains, as we venture into Rikka (May), the time when ‘Sweet Flag Bath Keeps Evil Away’. This relates to the way the Shobu-yu is a bath in which leaves of Shobu plant are soaked to ward off malevolent spirits and purify body and mind.

The sound of crickets lead us into Shoman (June), when ‘Everything Is Livelier’. The philosopher-chef wanders across bamboo fields while reflecting on the way to find the resolve to be on your own through separation. The protagonist food of the Boshu (June), the time of ’Nourishment For The Rain’, are pickle plums. This delight serves as a great teacher for the ritual that goes in the making that is integral to zen. Plums have a medicinal value and are a staple food.

‘The Sun Comes Out After The Rainy Season’ during Shosho (July), while ‘The Twilight Call Of Cicadas,’ in Risshu (August) ‘The Twilight Call Of Cicadas.’ The saliva glands tickle the tongue as they are stimulated by chestnuts, Yugao fruit, Myoga ginger and arrowroot powder. The autumn quietly tiptoes in with the approach of Hakuro (September), the moment characterised by ‘Dew On The Leaves.’ The Earth is bleeding with its vermillion hue as family losses and the acknowledgment of our own mortality affect Tsutomu.

But resilience provides the former monk more time on the planet to cook and philosophise during Shubun (Autumnal Equinox) ‘Return From The Other Side.’ We travel alone, we are born alone and die alone is what Tsutomu reminds himself while thinking about what Kenko Yoshida wrote in Essays in Idleness. Death sneaks up from behind and scratches us away, this is part of the season of life that is epitomised by the The Harvest of Leisure. This theme takes over in the unfolding of The Zen Diary as the beauty of nature becomes indissoluble from the importance of life.

‘The Clear Air Is Chilly’ during Kanro (October) and helps remind that Zen teaches you to abandon all obsessions. Transience is intrinsic to life as reminded by the season of Soko-Late (October) ‘Frost On The Ground’ and Ritto (November), when ‘Cold Northerlies Blows.’

This stupendous array of life lessons, granted through the culinary art and a minimalist denouement, find its conclusion with Touji (Winter Solstice), and the auspice to ‘Eat Well And Pray For Good Health.’ Throughout The Zen Diary the ascetic lifestyle and dishes as model of simplicity, feed the soul with elegance and meaning.

Final Grade: B+