It was fate that brought them together, “Banel & Adama.” Their love is stronger than centuries of traditions, tougher than the stubbornness of the land. It almost seems to border on madness. But it’s not easy to love unconditionally for a young Senegalese couple when the sun, the superstitious and the customs are against them. Playing at Lincoln Center’s “Rendez-Vous With French Cinema”, “Banel & Adama” is not only a dreamily haunting and gorgeous love story with a riff on “Romeo & Juliet,” but also an apocalyptic climate change premonition.

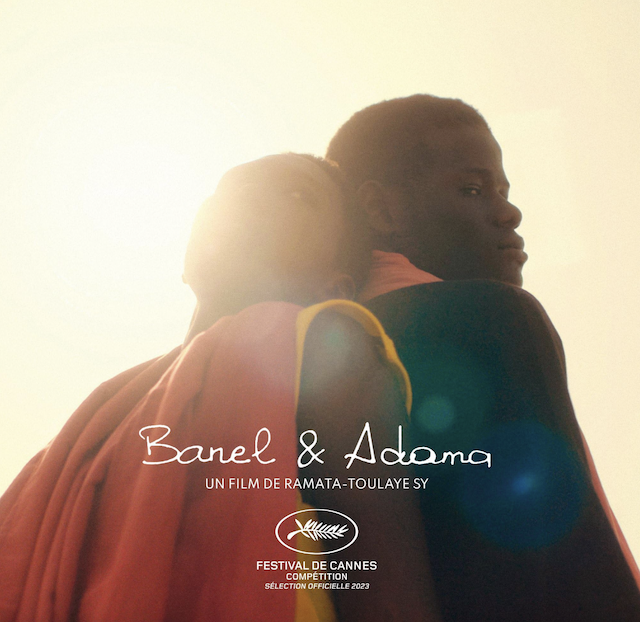

French-Senegalese director Ramata-Toulaye Sy received lots of attention last year with her striking debut feature – she was only the second black woman to compete for the Palme d’Or at Cannes Film Festival. Her French-Senegalese compatriot, Mati Diop (“Atlantics”, 2019), was the first four years earlier (Diop won the Golden Bear for best film with “Dahomey” at this year’s Berlin Film Festival).

Ramata-Toulaye Sy was born and raised in Paris suburbs and decided to set her film in Senegal– she is the daughter of Senegalese immigrants with one foot in Senegalese culture. Aware that most contemporary African films are about violence, war, terrorism, and poverty, the young literature enthusiast wanted to tell a great tragic love story, inspired by the classic heroines Medea or Phaedra of the Greek tragedy. Yet put her personal touch and mix magical realism, poetry, and the tradition of the West African griot.

The focus is on teenager Banel (Khady Mane). She is a rebellious and romantic girl with intense gaze, short hair, masculine T-shirt who sits with her legs crossed (that only men do), living in a rural Senegal village. After her first husband, Yero, died by falling down an open well, she married his younger brother Adama (Mamadou Diallo) – all according to Muslim tradition decreed in the small community. This was an incredible stroke of luck as Banel and Adama already were fiercely in love. So, things should be all fine for the young, passionate couple, but they cannot avoid the feeling that their happiness is founded on disloyalty to Yero’s memory. And the pressure and expectations from the community and traditions are suffocating.

Adama doesn’t show up for the prayers and refuses to take on the role of village tribute chief that is inherited from his late brother – he is only 19 years old. Banel, on the other side, is expected to take on traditionally feminine domestic responsibilities. But she has no interest in motherhood, washing clothes, prepping the fields for the coming rains, or looking after children. She “doesn’t want to live like that” and ignores the remarks and disapproval looks – the mother is furious at her behavior.

Banel’s yearning to free herself is the film’s center. Her pride, feminism, and break from harsh traditions are at the core – she only wants to live with her sweetheart in the dune houses that are buried under layers of sand outside the village. “Look at me. Aren’t I a woman?”, we hear her saying as she walks through the wind in the village. Her inner life seems to be filled with complex feelings. Not portrayed as passive nor humble, she shows sides that border on madness with a violent streak. When she kills a songbird on a branch and a lizard on a wall for fun with her orange slingshot, or drowns a fly with her saliva, she gives hints of what she is capable of.

Emphasized with dreamlike sequences, strong lights and Bachar Mar-Khalifé’s melodic score, we understand that this is not a typical teenage girl. To add to the peculiarities, we hear whispers of the couple’s names, which are repeatedly written on papers. She even seems to have supernatural features. Nuanced and fantastically played by newcomer Khady Mane, we slowly start to discover Banel. Nevertheless, she remains a mystery which keeps everything fascinating until the end. Her yellow t-shirt is somehow connected to the sun – she doesn’t seem to be from this world.

The place that she lives in has another world beauty – the camerawork by DP Amine Berrada is mind-blowing. Under the blazing sun, the colors are vivid, and the river is so blue. The shots are composed like paintings with a poetic touch, evoking the splendor of Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and Amoako Boafo. But this world is not doing so well. The rains won’t come, and the sun is merciless. People are dying, men are leaving the village, dead cows are everywhere – a catastrophe is lurking behind the trees. It’s a sudden change in weather that the villagers haven’t experienced before– the director makes a statement on the ongoing climate changes and its dramatic consequences, especially the drought in Africa.

Adama slowly becomes more troubled and the film more anxious. He blames himself, and is convinced that rejecting his position as the chief cursed the people in the village. And this weakens their relationship. Banel is left more and more alone and enters a vulnerable state of mind. But her desire is strong, and her independence is uncompromising, seemingly drawn from characters in Toni Morrison’s novels. Though her tendencies to enter madness seems to increase and the sweat on her forehead more visible. She doesn’t care about anything but to be with her lover. Repeat the names, Banel and Adama. Love is desperate but you cannot go against your destiny.

Grade: B+