Ainu means “human” in Ainu language. This is exactly the pursuit of film director Naomi Mizoguchi who through her Ainu – Indigenous People of Japan — part of the 2022 edition of the Chicago Japan Film Collective — shares the humanity of this culture nestled in Hokkaido.

The film craftily conducts this filmic experience through an Ainu language class, as words intertwine with the storytelling. We are guided to the nupuri (mountain), past the pet (river); we admire the elegance of a nonno (flower) and splendour of the kunne cup (moon); nature becomes bountiful thanks to the apto (rain), as all creatures manifest themselves in their utter grace, from the kikir (insect), to the cep (fish) and cikap (bird).

This anthropological film begins in the cold season, Mata (winter), and traverses Paykar (spring), Sak Atpake (early summer), Sak (summer), and Cuk (autumn). The circularity of the seasons epitomises the journey of transformation of a resilient culture that defied the will of a nation to annihilate it.

In fact, it was the year 1869 when the new government incorporated the Ainu into the nation and listed them as “commoners” on the family registers. Assimilation with Japanese culture was promoted causing Ainu language and culture to start to disappear. Furthermore, a hundred years passed since the residents of Anesaru were forced to relocate because of the construction of the Imperial Stock Farm. This community had to start anew in a rocky shaped area with little farmland. Many perished for famine and disease, but others survived and saved the heritage of the Autochthonous population. Despite all the hardships, the people captured in Mizoguchi’s documentary attest how this precious culture continues to thrive and will not be forgotten.

Ainu – Indigenous People of Japan portrays the lives of the people in the town of Biratori, also known as Ainumosir, Land of the Ainu. Photos and footage spanning from the late 19th century up until the Seventies, intertwine with interviews conducted in our present era. The 35mm film shot by Neil Gordon Munro in 1930 and the excerpt from Tonoto Kamuy, The Spirit of Sake directed by Shiro Kayano, are alternated with firsthand chronicles of Ainu history provided by the elderly who safeguard their praxis.

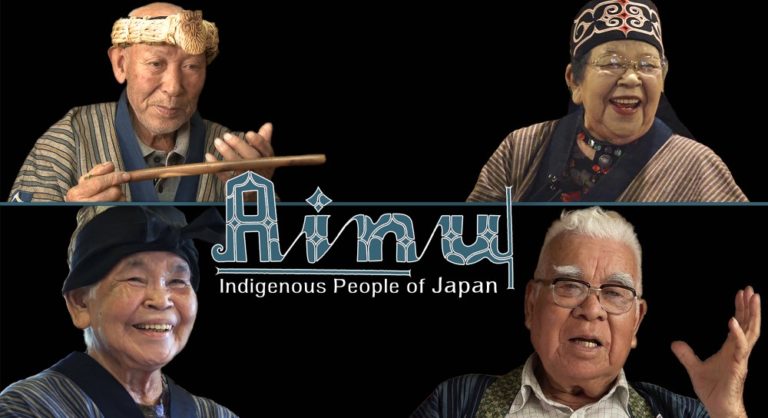

Spectators get acquainted with several of the main actors of this culture: Kazunobu Kawanamo, son of a mailman and housemaid who was the target of racism in his childhood who currently lives with his wife Motoko Kawanamo, an expert at boiling and drying tree bark; Tamotsu Nabesawa, a half Ainu and half Wajin (a non-Ainu person living in Japan); Sachiko Kibata, an instructor at the Nibutani Ainu Language School and member of the Biratori Ainu Culture Preservation Society who educates younger generations on the uepeker (old tales); Reiko Kayano, an expert in Ainu clothing and her husband Shigeru Kayano, the leading figure in the Ainu ethnic movement in Japan and the first of this culture to become a member of the Diet (Japan’s bicameral legislature); and their son Shiro Kayano, who is following in the footsteps of his parents to preserve Ainu culture.

The cinematic journey explores chimerical locations, like the Saru River before the Nibutani Dam was built in 1973, where the Ainu used to farm, live and hold ceremonies; the cip ta usi nay, where they dugout canoes; and the yam nitay, the chestnut forest. The latter would provide important food source for the Ainu community, since the acorns would be transformed into flour. The subsistence economy is further shown with the gathering of the tree barks, after asking the mountain deity for permission with the offering of sake. Millet is another natural ingredient that is core to the Ainu, who keep passing on from one generation to the next the secrets on how to harvest and pound it.

A blending of artistic expressions catapults spectators into the customs of these indigenous people, from the hararki (crane dance), to the emus rimse (sword dance) and the horippa (circle dance). Whilst the oral tradition is revived with lullabies of times gone by, like the nutap ka ta (On The River Shore) and the heroic Ainu sagas called yukar.

Many ancient customs and oral stories come to the light, from the story about Ponyaunpe to the reenactment of the Iomante — the ceremony in which a brown bear is sacrificed and sent back to the land of the deities. The spirituality of nature is disclosed through awe-inspiring legends, like the u ka e roski, known as the Mother Bear and Cubs Rock; the opus nupuri, the Mountain with a Hole; and the Matchmaking Rock that has led to many auspicious couplings.

The sensation after watching this vivid and true to life moving picture will be inebriating, something similar to what is described after a sip of sake, a state of uenewsar yaykoitak. When films like Ainu – Indigenous People of Japan come into being, they trigger a sense of gratitude for the way they bequeath the understanding of meaningful civilisations. Whilst audiences may remain speechless for the edifying experience, there is one word left to be uttered, which is thank you, preferably in Ainu language: lyayraykere [pronounced iyairaiker].

Final Grade: A-