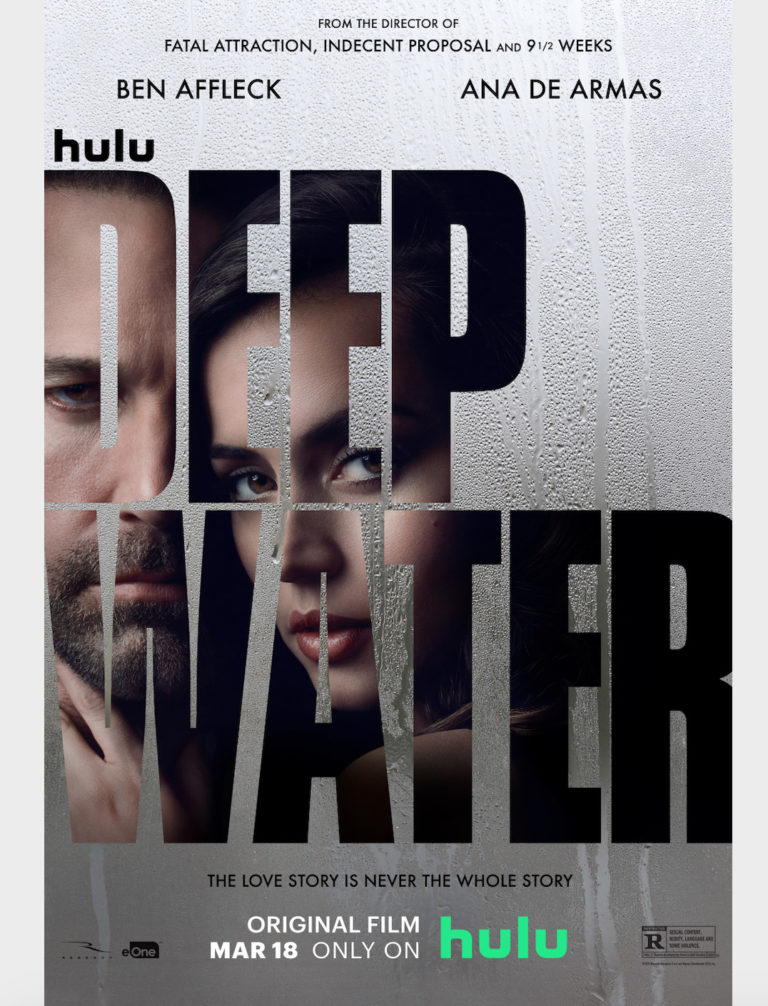

The director of Fatal Attraction, Unfaithful and Indecent Proposal, Adrian Lyne, returns to the big screen with psychological thriller Deep Water, starring Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas.

The film, distributed by Hulu, is based on the eponymous novel by Patricia Highsmith, known for penning also the famed book, adapted for the screen, The Talented Mr. Ripley. The screenplay of Deep Water, by Zach Helm and Sam Levinson, remains faithful to its inspirer providing a contemporary twist to the 1957 novel. The erotic dynamics are more sophisticated and the setting has been moved from Massachusetts to the stately homes of New Orleans’ Garden District.

In line with Highsmith’s inclination in reverting gender stereotypes and twisting conformist marital morality, the female protagonist epitomises a modern Madame Bovary. Melinda (Ana de Armas), and Vic Van Allen (Ben Affleck) live in an open-marriage. Mrs. Van Allen is the one who continuously has affairs, whilst her husband impassibly deals with them, focusing on their six-year-old daughter, Trixie (Grace Jenkins).

All their friends and neighbours are aware of this precarious arrangement that tries to keep the marriage intact. Vic is courteous, introverted and understanding. He is retired from his work as a microchip inventor, and enjoys his wealth by publishing a quarterly arts magazine, riding his mountain bike and tending to his snail farm. On the other hand, Melinda is what psychology would define as a covert narcissist: she craves admiration and importance, lacks empathy towards others, but camouflages her hedonism through her own sense of fellow feeling.

Deep Water plunges us inside the marriage between this adulterous and uninhibited wife, and her picture-perfect domestic husband. The dynamic of the victim and executioner takes an unexpected turn. The cat and mouse game is altered by Vic’s anger and jealousy that begin to boil, as libido probes the darkest aspects of power and control, that transcend mere sexual gratification.

The erratic gyrations in the plot give way to a continuous dominance-submission see-saw, within the sexual power dynamic. Just like Adrian Lyne’s previous films, the consequences for those who enter into illicit relationships uncover tales of obsession, betrayal and murder. This ultimately effaces the demarcation between the guilty and the innocent.

Although the story has elements of a crime drama, there isn’t Agatha Christie’s whodunit detective approach or Alfred Hitchcock’s MacGuffin plot device. In Deep Water the actual cinematic twist doesn’t derive from discovering the murderer, that is identified very quickly, but rather by meandering within the complex reasoning that is unleashed by lust, possessiveness and mind games.

Both Ben Affleck with Gone Girl and Ana de Armas with Knives Out had prepared for a psychological mystery thriller of this kind, and together they are dynamite. Affleck’s Vic is imperturbable and chilled in his ruminations. Whereas de Armas’ Melinda is impulsive, voluptuous and acts as the wick that will trigger the reactions of her husband. The true star of the film is Grace Jenkins, playing the smart cookie daughter who delights in every scene.

One of the most impressive traits about Deep Water is how it channels the spectators’ empathy towards an amicable, maltreated individual who, as a reaction, acts unlawfully. Hence, the question that remains open is whether the malfeasance can be considered immoral, since it tries to contrast the environing wrongdoing. The audience thusly acknowledges how much behaviour is determined by conditioning, as it simply responds to a stimulus.

This idea echoes throughout Deep Water with Vic’s passion for heliciculture. He shapes himself with the same endurance he practices snail farming. The shelled gastropod somehow represents his animal spirit: on the outside his strong and grounded armour shields his sensitive and frail nature, that eventually gives way to certifiable deeds. Just like the snail can call its shell home, Vic finds shelter in the facade of the forbearing cuckold. Inside this spiralling haven, that protects from the hazards of the outside world, is a slimy and slippery being that quietly and slowly extends its antennae to detect his surroundings before taking action. In this fashion, vicious comportment, that rises when one is in “deep water,” finds its unmitigated personification.

Final Grade: B+