©Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

When filmmaker Raoul Peck took on the iconic James Baldwin (1924-1987), in his Oscar-nominated documentary I am Not Your Negro (2016), he wanted the writer himself to tell the story, not by a narrator like in a regular biography. Samuel L. Jackson read Baldwin’s profound words like he was him and carried his soul.

In Peck’s new film, about the South African photographer Ernest Cole (1940-1990), once again an actor, this time LaKeith Stanfield, becomes the artist. Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, winner of Golden Eye for best documentary at Cannes Film Festival, could be considered a companion piece to Peck’s previous successful documentary – with another black, bold artist, a fearless truth-seeker with self-doubt in miserably racist times. It’s a timely, poetic and extraordinary portray.

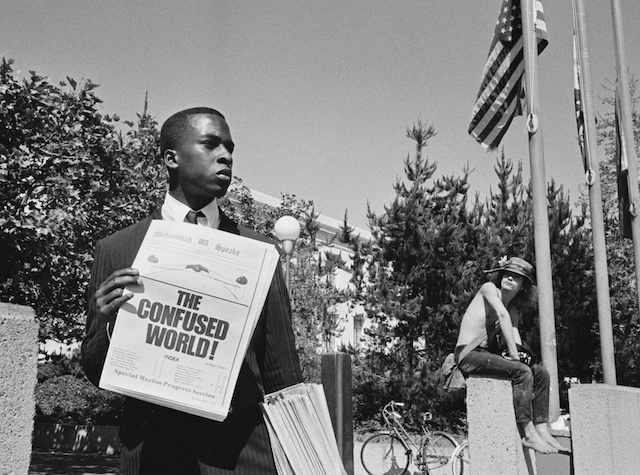

At the age of 27, Ernest Cole was as one of the great photographers of his time and one of the first Black freelance photographers in South Africa. Living at the height of apartheid, Cole became famous with his book of photography House of Bondage (1967), which was banned in South Africa and revealed the horrifying realities of black life to the world. Cole had to move to US to publish the book and was never able to return. 50 years later, in 2017, 60 000 unknown negatives were found in a bank vault in Stockholm, Sweden. With Cole’s own words and his astonishing photographs, this documentary tells the story of what he encountered in between.

Cole risked his life every day taking the photos, when collecting evidence in the South African society. He started to work for publications like Drum and Bantu World and became inspired by Henri Cartier-Bresson, the French humanist photographer who pioneered the genre of street photography. In South Africa a black person didn’t have the right to walk freely on the streets of his own country, always had to carry a pass, a reference book. A pass that could be pulled at any time by the police for no reason and with no warning, which happened thousands of times a day.

©Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Black people were fired, arrested, abused, tortured, murdered and forced to work as domestic helpers who were paid $15 a month, in service jobs and tough jobs in mines –gold was one of the sources of South Africa’s wealth. “If nobody complained, they think you are happy. If you do complain, you are ungrateful”, Cole said. Millions of black Africans were removed from their homes and forced into segregated tin-roof government ghettos. In this morbid system of separation signs were seen everywhere: Whites only. Europeans only. South Africa was a land of signs. This was a reality as tolerable as a bad climate.

Cole captured every moment of this reality. He never judged, he observed, amazed and appalled. What we see in the documentary, so delicately put together by Peck and editor Alexandra Strauss, accompanied by Alexei Aigui’s original music, is the essence of human life. We also see Cole himself in an interview by Rune Hassner, various videos of people on the streets and political aspects, such as the hypocrisy of world leaders like Jacques Chirac, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

Cole’s photographing had consequences. He was aware that after finishing House of Bondage he had to escape the “living hell that is South Africa”. “A total man doesn’t live one experience”, he said. He moved to New York 1966, after a stay in Europe. But what Cole in exile felt after arriving was not the great racial promises, but shock and lost feelings. Yet he did capture a freedom he’d never seen – liberated women, interracial and gay couples. But it wasn’t a freedom he could be part of. He was an isolated figure, out of sorts, homesick and depressed. He discovered, as a failed photojournalistic in the Southern states, that the “true America’ wasn’t much different from South Africa. He was afraid of being shot in the US. Black people were oppressed and should know their place. Apartheid there. Jim Crow here.

Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck has crafted a melancholic and tender film told through the power of Cole’s photos and his words from letters and journals etc., sensitively voiced by LaKeith Stanfield. Peck seems to be particularly interested in Cole’s torn mind, loneliness and melancholia. In South Africa he could not live, in USA he was an outsider, a foreigner – the other. He felt separated from Black Americans and pushed away by racist white people, initially thinking US would open its arms to him. This reality of being without country, as he shared with various other South Africans such as the musicians “The Manhattan Brothers” and Miriam Makeba, was tearing him apart.

He became more and more isolated. He felt a sense of betrayal. Yet, he never drank, took drugs, and was able, at times, to spend time in Sweden, Denmark and England. And it was in Sweden, in a bank vault in Stockholm, the negatives of many of his photos had been hidden. Others had been lost in New York. Ernest Cole’s uncle Leslie Matlaisane, who lives in South Africa, was informed in 2017 and went to Stockholm to pick them up. Until today it is not revealed how they got there, and by whom.

Ernest Cole did stop taking photographs for 8 years and became homeless. His book was forgotten, and he declined mentally. “I’m homesick and I can’t return”, he says. The nagging feeling of rootlessness never disappeared. Just a few days after Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, and Apartheid ended, he died of cancer 49 years old.

This exceptional documentary shines a light on an enigmatic man in a horrifying era. A man who always believed that South Africa one day would be free. Just as his vital and incomparable photographs, that have now found a new life, we get a glimpse into a soul of a man who was robbed of life in peace. He will never be forgotten.

©Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Grade: A-

Ernest Cole: Lost and Found is screened at DOC NYC and will be released by Magnolia Pictures in theaters November 22

If you like the review, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Niclas’ articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.