The line-up for the 2023 edition of JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film includes the film Wandering, also released with the title The Wandering Moon. The movie directed by Lee Sang-il is based on the novel Rurou no Tsuki by Yuu Nagira, winner of 17th Japan Booksellers’ Award in 2020.

Fate brings together two lone wanderers. These are the introductory words to a disturbingly awakening picture about the way appearances may be deceiving.

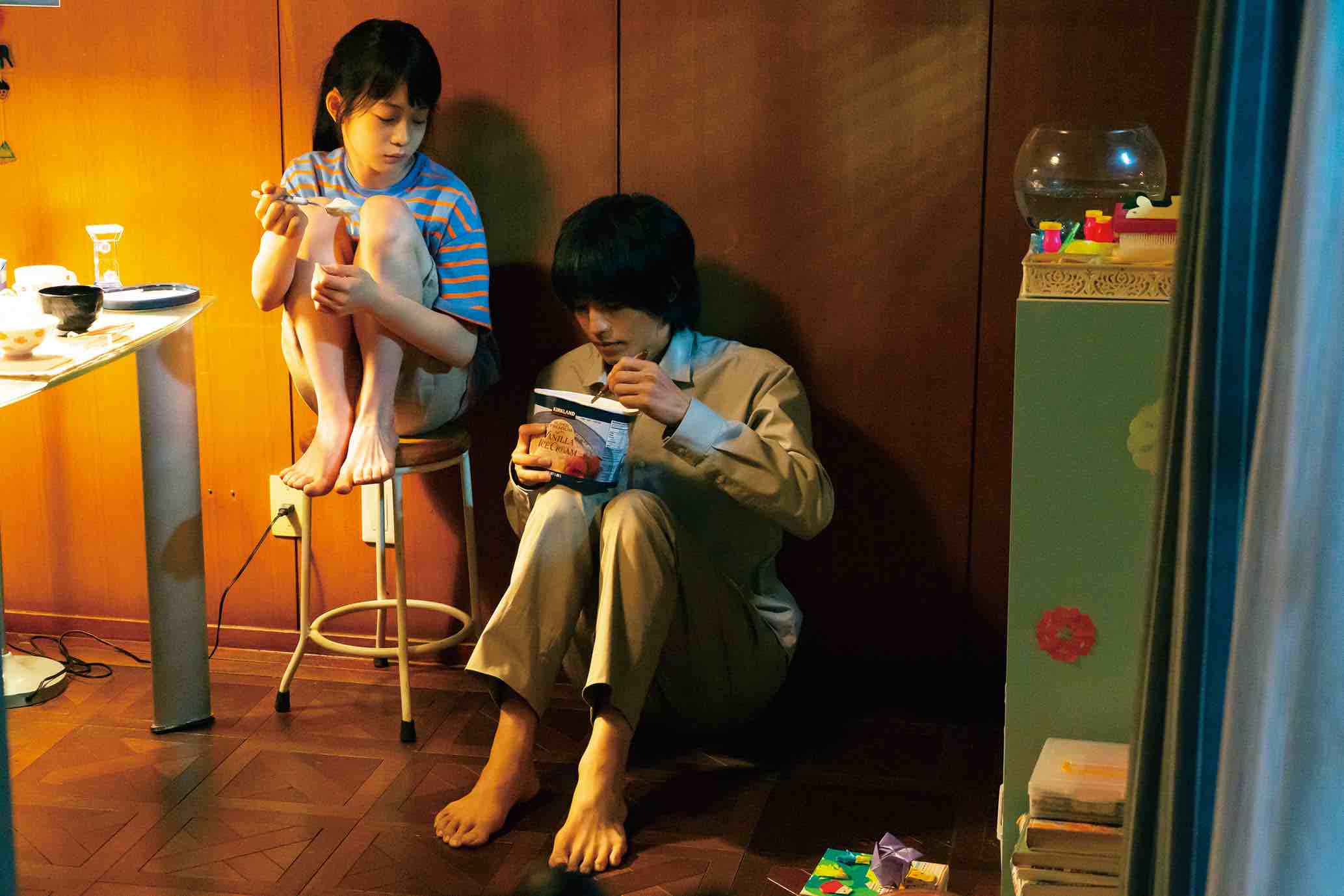

Fumi Saeki (Tori Matsuzaka), is a student who, on a rainy afternoon, meets a little girl named Sarasa Kanai (Tamaki Shiratori) in a park. She is all alone and does not want to go back home to her aunt, with whom she lives. Fumi takes Sarasa to his apartment where they live together for two months. What is shown is a pure and caring interaction between them, that implies no sexuality or abuse of any kind. Yet Fumi is accused of kidnapping a minor and branded by society as a dangerous person. Fifteen years after this incident, Sarasa is working at a restaurant and living with her boyfriend Ryo (Ryusei Yokohama), whose controlling nature gives into violence. One evening Sarasa goes out with a friend, after work, and they end up in a mystifying coffee place called Calico. She discovers it is run by Fumi. The young man has a a girlfriend, Ayumi Tani (Mikako Tabe), who ignores his past. Circumstances suddenly bring Fumi and Sarasa back together and the two find themselves in the eye of the storm once more, when the young woman is entrusted by her friend, Kanako Anzai (Shuri), with her ten year old daughter Rika (Mio Masuda).

In Wandering there is a cameo by Akira Emoto, winner of the Japanese Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in Dr. Akagi. His appearance, albeit instantaneous, is particularly influential in setting the tone of the film. He plays a character who Sarasa fleetingly meets, before seeing Fumi after over a decade. The elderly man runs an antique shop below the coffee place and, as Sarasa admires a Baccarat glass, he tells her how things are like humans: we meet, part, then meet again.

Throughout the narrative a deluge of memories and recollections intertwine, retracing the connection between Fumi and Sarasa, that challenges moral complexities where there are no resolute answers. The film keeps you wondering if Sarasa suffers from Stockholm Syndrome and if Fumi ever acted inappropriately towards the young girl. But since the film is not coy in showing moments of sex — for instance the ones between Sarasa and Ryo — the fact that there is no allusion whatsoever to Fumi abusing the minor, leads audiences to believe that this bond was one that society could not understand and decided to sully. However, the psychological intricacy that makes the drama even more compelling and thought-provoking is how Fumi admits to having a fascination for little girls, possibly one that was never expressed. There is no black or white definition to the nature of the relationship between these two individuals, who share a repulsion for sexuality, and this makes the film far from banal and exceptionally heartrending.

At one point in the story Fumi reads some poetry that perfectly captures the way he experiences being in the world:

“From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were —I have not seen

As others saw — I could not bring

My passions from a common spring —

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow — I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone —

And all I lov’d — I lov’d alone —

Then — in my childhood — in the dawn

Of a most stormy life — was drawn

From ev’ry depth of good and ill

The mystery which binds me still —”

Edgar Allan Poe’s verse mirrors not only Fumi’s state of mind but also the construction of Sarasa’s identity. She was alone while society was labelling her as a victim. But already as a child we had a glimpse of her fortitude and independence of thought. Fumi was the one who allowed little Sarasa to release her inner spirit. The ten year old girl obliged Fumi to eat pizza and ice-cream and preferred to read Poe’s poetry instead of the more conventional children classic Anne of Green Gables.

Adulthood proves to be far from being liberating. Social constructions and expectations are the cause of self-censorship. Sarasa the woman eventually forced herself into a quiet acceptance of situations, until she met Fumi again. Thanks to him she finds the strength to break free from her cage, emerging as a gentle fighter who never ceases to be benevolent to all those around her.

In a time when there is much debate about overthrowing the patriarchy, Wandering sends a feminist message from the male gender, proving how men should be part of this conversation. When Sarasa and Fumi are separated, the young man tells her “You belong to yourself, don’t let anyone own you.” This is just one of several humanising instants in the film.

In his latest work, Lee Sang-il masters the complexity of the human spirit and how people have the tendency to remain on the surface of things. Members of society only see what they want to see, and this may cause tremendous distress to individuals who are difficult to categorise. Once your reputation is compromised there is no going back. Yet if chance allows a vibrational match between two people, they can find the courage to follow their own…wandering.

Final Grade: A