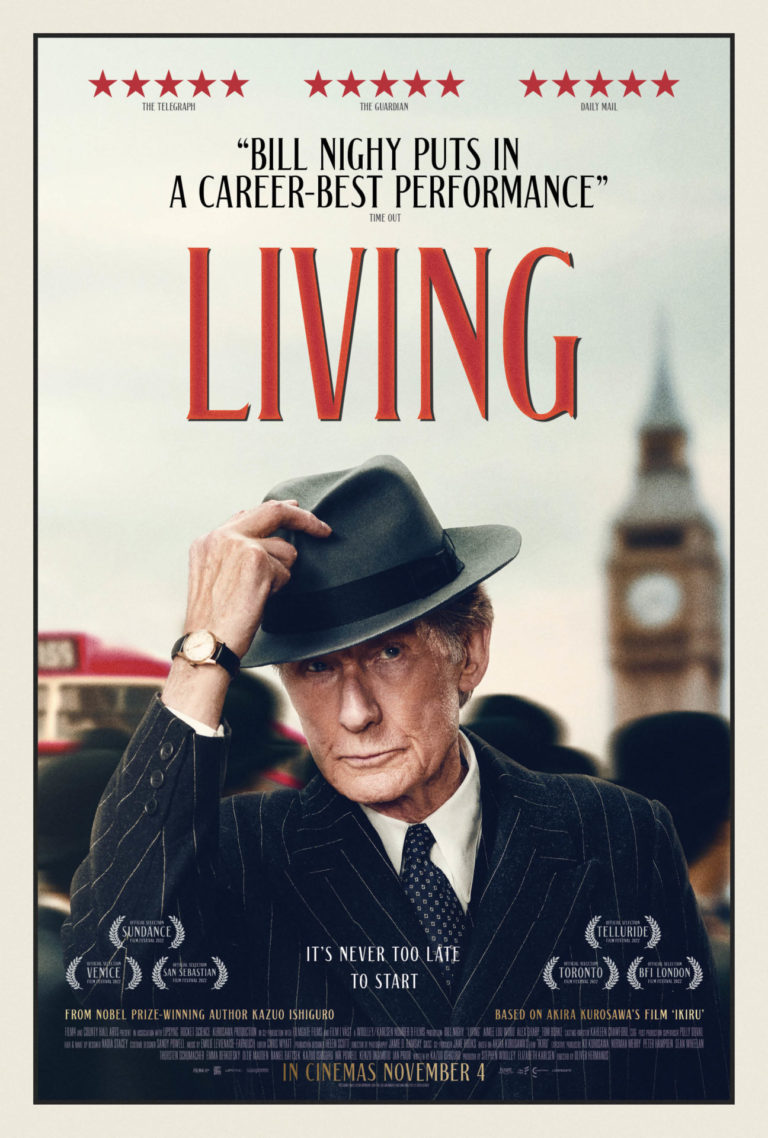

South African filmmaker Oliver Hermanus takes a spin on the 1952 Japanese film Ikiru directed by Akira Kurosawa. The original screenplay by Kazuo Ishiguro — inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 Russian novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich — finds a modern adaptation with the British drama Living.

The film is set in London in the early Fifties, where a bureaucrat played Bill Nighy is facing a fatal illness. Mr. Williams is the head of a London municipal office in charge of granting authorisations to use public places. He is a misanthrope, a Scrooge-like figure. But as we gradually get acquainted with him we discover he is not devoid of sensitivity. His introvert nature prevents him from confiding his fatal health situation to his closest family members or colleagues. Only a young new employee, Miss Harris (Aimee Lou Wood) wins his trust through her bubbly spirit.

Oliver Hermanus has a very elegant filming style, as he opts to shoot in a 4:3 aspect ratio that conveys the necessary nostalgia for the period setting. In terms of themes the film — that had its world premiere at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival — comes across as a Dickensian parable about mortality and second chances. Yet, the efficacy of Living rests on the shoulders of Bill Nighy, who manages to convey emotional transportation without uttering a word. His imperturbable facial expressions, that show how someone like Mr. Williams would interiorise his feelings, are a brilliant demonstration of invisible acting. The cinematic impact is overwhelming and provides meaning to the entire story, compensating all the moments of silence. The non-verbal dialogue speaks louder than any outburst of rambling words. Bill Nighy’s British aplomb and the cultural migration of the story makes Living an effective prototype of humanist cinema. This draws him close to the dignified composure towards pain and suffering of the original employee Kanji Watanabe, who marked the history of cinema as the epitome of pessimism turned into desire of redemption.

The entire process of adaptation of this story resembles other occasions in which Japanese storytelling found a voice through a British filmmaker. In fact, Nobel Prize-winning Kazuo Ishiguro, who is the screenwriter of Ikiru, had written the novel that James Ivory adapted for the screen: The Remains Of The Day. Also this story unified the apparently distant Western and Eastern mentality, showing how devotion to duty may smother the personal sphere. Mr. Stevens (The Remains Of The Day) just like bureaucrat Mr. Williams (Ikiru) led a life where unspoken feelings left a trace of regret and unfulfillment.

Living diligently follows Ishiguro’s themes, as well as the entire directorial structure of Kurosawa’s film — that so brilliantly dissected the indictment of bureaucracy with its farcical, purposeless and robotic productivity. Hermanus keeps the pace of the motion picture that inspired his latest work and repurposes most of the narrative denouements and the character’s gestures. He follows Ikiru by the book, making Living a mere copy of the original masterpiece. However, it cannot be denied that this remake manages to treat one of Kurosawa’s greatest films with the utmost respect. In an entertainment business that is bombarded by action heroes or biopics about extraordinary existences, Hermanus is worthy of praise for bringing back to the silver screen the story of an ordinary life that is equally meaningful and special.

Final Grade: B-