Two Japanese filmmakers who have made waves have sparked conversations with arthouse filmgoers. They have already prompted some of the most interesting debates on the festival circuit at Cannes, Venice, Toronto and now New York. Both high-profile, award-winning Japanese directors Hirokazu Kore-eda and Ryusuke Hamguchi have posed questions to their audiences through their film titles: “Monster” and “Evil Does Not Exit” respectively. Hanging over our heads throughout each film is a question — who is “Monster” or Why “Evil Does Not Exist”?

But of the two, the great Hamaguchi has returned to New York only two short years after he garnered the Oscar for “Drive My Car” which elevated him to the top tier of global filmmakers. Now, with “Evil Does Not Exist,” he has created an enigmatic drama which tiptoes along the edge between ecological fear and the uncertainty of human behavior. The film started as a short accompaniment to a musical piece by the phenomenal composer Eiko Ishibashi but was then expanded into a full feature.

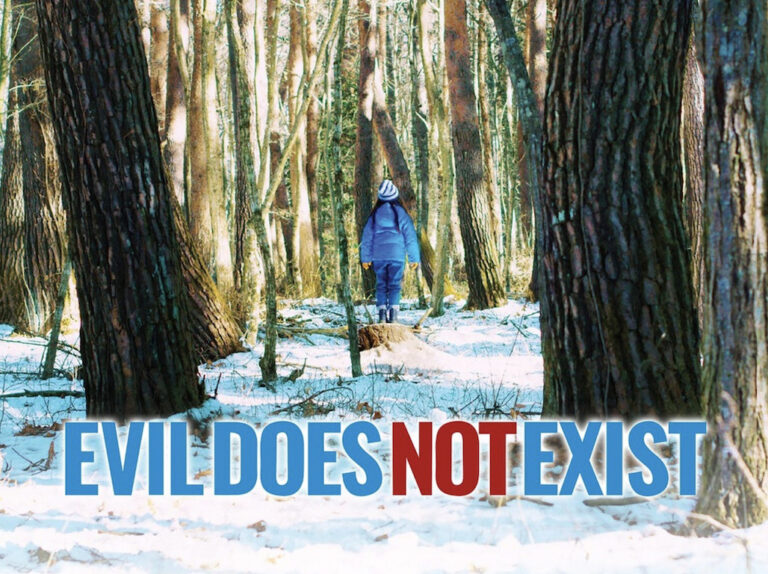

A local jack-of-all-trades Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) lives in a Mizubiki village, a small, isolated but tightly knit countryside community which offers relief from the hustle and bustle of Tokyo’s city life. He and his eight-year old daughter Hana lead a simple life — seen in long scenes in which Takumi chops wood and collects water from a river for a nearby noodle restaurant; they walk back together through the forest after Hana finishes the school. These sequences are beautiful looking and tranquil; the camera lingers on creeks, snow-covered woods, mountains, the deers, and shows their reliance on nature for their way of life.

But the serenity of this community is threatened by a new business project which tries to woo the local people to accept “Glamping” [glamorous camping] to bring more business to the region. It is initially presented as a positive force for the community until two underprepared agents (Ayaka Shibutani and Ryuji Kosaka) — representing the Playmode Corporation, — host a town hall with residents to get their input. The townsfolk slowly realize this affects the undisturbed harmony of the local ecosystem so tear apart the pitch to shreds because of its impact on practical and preservation concerns. The two agents haven’t considered many things that could go wrong such as septic run-off and fire hazards. The sequences in which they interact with the villagers display a strong sense of comedic timing and satirically address the corporate thinking.

The agents eagerly get involved in Takumi’s life, even asking him to be the caretaker for the impending construction of a massive recreational retreat, by taking Takumi in their side, they thought he could help them win over the locals, but we soon see that the two agents have their own reservations about the company and their dead-end jobs.

While Both sides negotiate, adolescent daughter Hana (Ryo Nishikawa) strolls through the forest which have become less appealing to the presence of ungracious visitors who start bonfires and hunt for sport, leaving the deer on the defensive.

Throughout the film, Hamaguchi tries to show how such ecological problems can often be solved by listening and understanding the land itself. Initially, the nature sequences are beautiful and tranquil, capturing the natural flow of the local people’s lives. But as the film proceeds, tracking shots of scenery becomes darker and feel more isolated, lending an ominous feel to the film as if it’s a metaphor for the looming peril of gentrification and its encroachment on the natural world — which is something that’s about to happen.

This leads to a surprising ending which some may find to be rather random, but Hamaguchi forces us to reckon with the industrialization of nature.

What’s also surprising about Hamaguchi is that he takes a nuanced approach to both sides and never makes the intrusive company “The Villain.” Even if we do understand that their plan is deeply flawed, it makes sense why the title is “Evil Does Not Exist.” Yes, it is closer to being a villain who disrupts the harmony of nature [for the deer] and Hana [who represents the locals] at the end, he gets punished. This has baffled some folks, but cinema these days is all about answers and clues. It is admirable that at least one artist asks such questions of us. Designed in such a way to incorporate contradictions, it pulls us simultaneously back and forth between opposing emotional responses.