©Courtesy of Neon

To avoid an eight-year prison sentence for making his latest film The Seed of the Sacred Fig, Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof fled his native country to begin a life in exile. In two hours, he made the decision to embark on the risky escape on foot across the mountains. Two weeks later his film had its world premiere at Cannes Film Festival where he showed up and won the Jury Special Prize and the Fipresci Award. It’s an unsettling and incredibly tense film that uses a sharp sledgehammer to criticize the Iranian regime and its misogyny, theocracy, and cultural repression.

After the escape Rasoulof declared that “I have many more stories to tell, that’s what persuaded me to leave Iran.” The story in The Seed of the Sacred Fig focuses on a middle-class family in Tehran. The father Iman (Misagh Zare) is a true patriarch. He is a lawyer who has just been promoted to state investigator for the Revolutionary Court (the very one that sentenced Rasoulof himself) which gives him a higher place in Iran’s judicial hierarchy. His pious wife Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) is initially pleased, much less so are his outspoken, independent-minded daughters Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki).

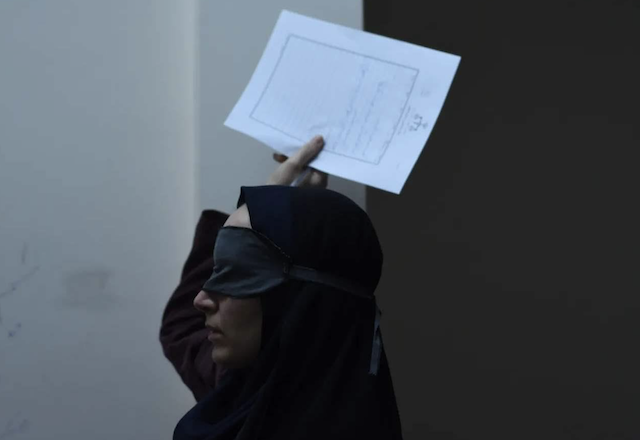

Now that Iman has become more important in the state, the family has clear instructions on what is required of them. They may also receive threats. At the same time, by coincidence, a series of student protests against the government have exploded in the streets. The daughters are sympathizing with the protesters and try to help their classmate Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi), who has been brutally attacked. The paranoia and tensions in this cat-and-mouse thriller have begun.

©Courtesy of Neon

The protests are depicted through harrowing real-life footage of police brutality, on TikTok and Youtube, of the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement that burst forth following the murder of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was arrested for allegedly not properly wearing the headscarf. In the film, Iman gets more serious in his new work role, signing death-penalty indictments against activists without giving due process. Increasingly his family clashes with him.

There is a gun involved. And it’s missing. A handgun that triggers more tensions and makes Iman panic and paranoid. He received it for his work for family protection and a misplacement can give a punishment up to three years in prison and risks his further promotion. After the discovery of the missing gun, the movie shifts mood to a nerve-racking domestic thriller and moves from the family’s claustrophobic apartment in Tehran to Iman’s childhood home in the countryside.

During Iman’s demands for someone to confess to taking the gun, the film suffers a couple of script flaws denying it from being called a true masterwork. Nevertheless the film is exceptional. Rasoulof is borrowing the narrative principle referred to as Chekhov’s gun, where the gun first seems unimportant but will later have huge significance.

©Courtesy of Neon

Rasoulof’s brave screenplay is sharp as a freshly sharpened knife. The editing is seamlessly fluid. His style, at least in the first half, is familiar in Iranian cinema, and reminds you of the films of directors Asghar Farhadi (A Separation, 2011) and the banned Jafar Panahi (3 Faces, 2018). Being one of Iran’s leading filmmakers, Rasoulof has twice served time in Iranian prison, once for having filmed the otherworldly The White Meadows (2009) and in 2017 he had his passport withdrawn. His film There is No Evil (2020) won the Golden Bear at Berlin Film Festival, but he was banned from attending. Copies of his films Goodbye (2011), Manuscripts Don’t Burn (2013) and A Man of Integrity (2017) were secretly sent to the Cannes Film Festival to be screened.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig was shot entirely in secret and his cast and team are still at risk in Iran. Nevertheless, Rasoulof continues to create intriguing and intelligent films criticizing the Iranian regime, despite constant repression. The title The Seeds of the Sacred Fig is explained in the beginning. The seeds circulate into the branches of other trees, and slowly choke the life out of its host. Rasolouf warns us that the story is urgent and relatable for everyone, even those who don’t live under oppression. He believes that with youth, change will come.

Grade: A-