The expectations with being cinema’s greatest and most respected animator can be heavy weights on his shoulders. But director Hayao Miyazaki surpassed those with a humble spirit. With his latest “The Boy and the Heron”, the 82-year-old delivers a movie experience that makes the jaw drop down to the stomach. In Toronto, where it premiered internationally after making a splash in Japan, the wind rose during the screening. Those lucky ones getting a ticket in the packed theater embarked on an astonishing journey of loss and love with a little boy, a bizarre heron, an Einstein-lookalike great-uncle, capricious giant parakeets, and a gang of protective little nannies.

A decade after his last film, the Oscar nominated “The Wind Rises” (saying he would retire at that time), the film begins with a boy named Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki). The 12-year-old is waking up to the sound of warning sirens in Tokyo. It’s World War II and the town hospital is burning. Knowing his mother works there, he desperately tries to help and runs through the streets as red-orange flames filling the night sky. But he is too late. The building collapses with his mother inside.

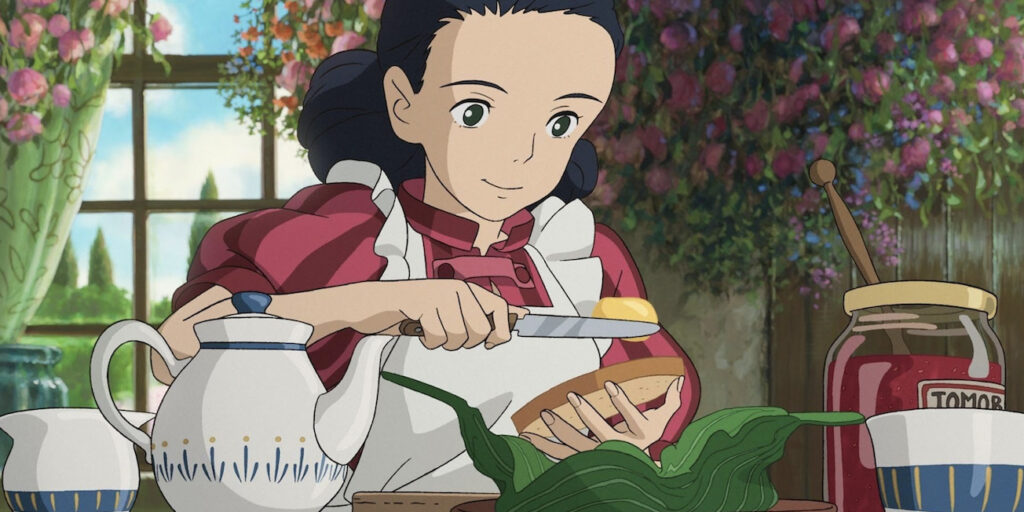

A year later the boy and his father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura) have moved to the countryside where his father works for a company that makes wartime planes for Japan (as did the director’s own father). He has married his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura). Mahito is not happy, and he hates his new school. Here the grey heron (Masaki Suda) is introduced. At first casually, yet he will have an important and unpredicted role that changes the boy’s life forever. He seems to be fascinated by Mahito, and vice versa. After getting into a fight in school, Mahito hears the heron murmurs “help me” from his bedroom window and quickly leaves. Compelled and curious, the boy follows him to a mysterious tower, seeing the heron fly into a window. Although the entrance is sealed off, Mahito manages to climb through a small opening. In the tower, he crosses into a world of multiverses and secrets and the film heads toward the supernatural, blending reality with fantasy and surrealism.

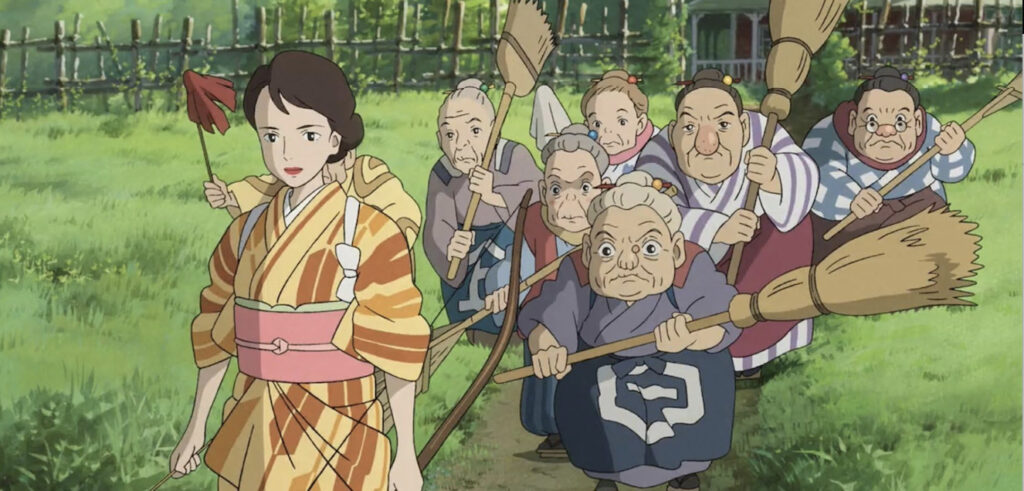

Moving with fluidity, this striking fusion is fully plausible. The passage of time and space blends together and we embrace it all. As well as the cute, ghost-like creatures called Warawaras, big fascist parakeets and hungry pelicans who are starving because the sea is cursed. They evoke both laughs and chills. And at the center stands the talking heron, who soon behaves like a cryptic vulture claiming Mahito’s mother is alive awaiting the boy’s rescue. Inside the tower, a beautiful grand chamber with mosaic floors opens and we meet a gnome-like old man who lives inside the heron. He and Mahito sink together through the floor into another layered, wonderous world.

Mahito’s emotions of sadness and mourning are the trigger to this otherworldly experience. Sometimes he dreams of his mother. Naturally Miyazaki’s preoccupation is the boy’s loss but even more how it evokes this other limitless world between life and death. The director once said that the mission with his films is to comfort you. To fill in the gap that might be in your heart or your everyday life. Here perhaps a comfort for everyone who lost a mother, or anyone close.

Miyazaki was born in 1941, during World War II. As a boy, his mother gave him Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel “How Do You Live?” to read. It was the original inspiration for the film and the Japanese title. The title’s question is a perfect fit for the story as it expands into an existential and life affirming tale about interconnections and changes, with the grey heron as part of Japanese folkloric.

The film was once again made by Studio Ghibli, the animation company Miyazaki co-founded in 1985, that gives him the possibility to control every detail of his films. Miyazaki has a uniquely beautiful way of creating layers under layers, slipping in and out of chaos and harmony. Every frame is a hand-painted canvas, with depth and emotions. For Miyazaki “The Boy and the Heron” is very personal and draws upon the director’s own childhood. His family also fled the bombing of Tokyo and moved to the countryside. Although his mother lived until much later, she was a source of inspiration. Just as Mahito’s mother in the film is, despite having left the earthly life.

The iconic director, who has invented such magical works and visual splendor for decades, once again nails it with an intoxicating, bold and loving exploration of grief, acceptance, and wonder. Nothing is a farewell, only a comfort to fill your gap. Your presence is requested.

Grade: A

Check out more of Niclas’ articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.