In the opening scenes of George Stevens classic “Giant” (1956), Rock Hudson’s character arrives on a steamy train looking out on a green Maryland mid-1920’s landscape. He’s a tall, butch, handsome, and rich Texan rancher with a fondness for riding stallions – his cowboy hat is huge, and his eyes are gentle. Standing on a porch a short time later, Elizabeth Taylor falls for his charm and a skeptical James Dean will become his rival (the latter famously had real-life rivalry with Hudson and died in a car crash at 24 before the film was released).

Like the character Hudson played in ‘Giant”, which earned him an Oscar nomination and is considered the best portrayal of his career, he knew how to make women fall for him and became an archetype of how a straight Hollywood heartthrob man should be. But his personal life was very far from his movie roles. As a gay man in a homophobic world, Hudson had to lead a double life to maintain a career. His premature death due to AIDS-related complications in 1985 led to many people changing their attitudes regarding the disease – Hudson was in a way an activist without knowing it and paved the way for others.

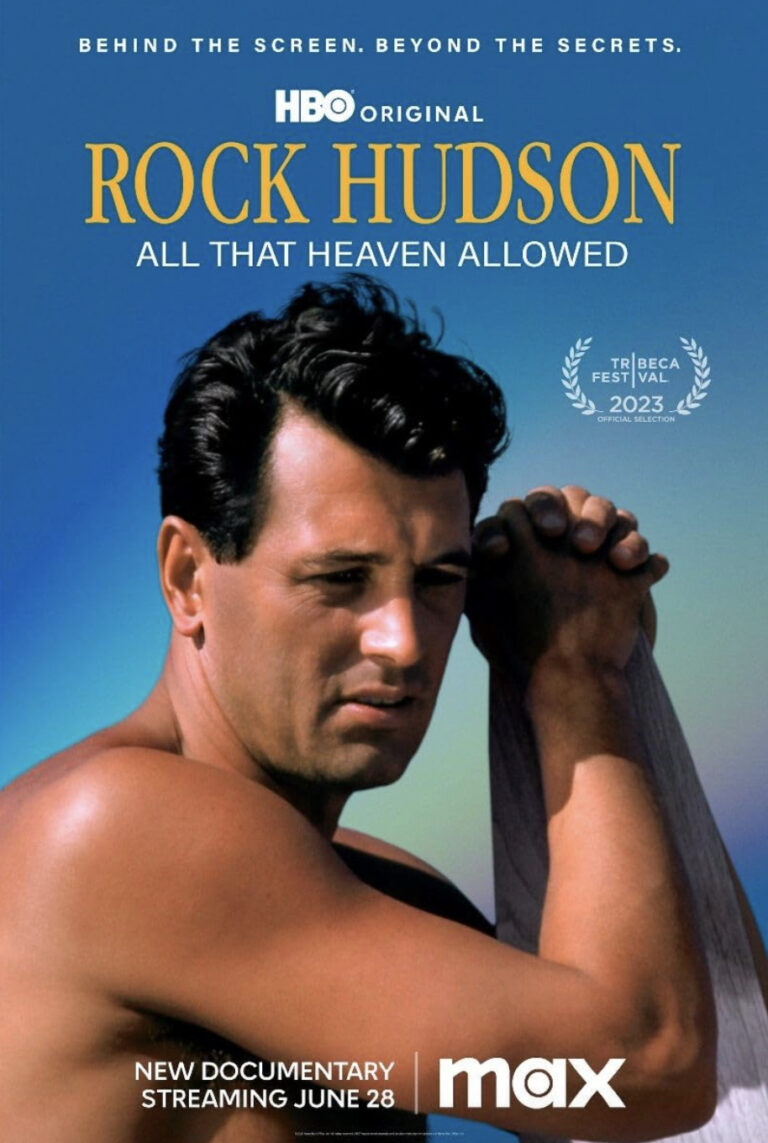

The pulsating, entertaining and moving documentary “Rock Hudson – All That Heaven Allowed” by Stephen Kijak, premiering at Tribeca Festival, offers a look at both the public and private life of the biggest star in Hollywood at the time – the Tom Cruise of his day. When Hudson burst onto the scene at the end of the 1940s, just after World War II (Hudson served in the navy during the war), there was a craving for macho stereotypical quality in movie actors – horse-riding butches with big physiques and low voices, very different from the silent movie star types like Ramon Novarro and Rudolph Valentino. Rock Hudson, called the Baron of Beefcake and the Gentle Giant, seemed to fit perfectly into this need in the studio system. His appeal was undeniable.

Born Roy Harold Scherer Jr. in 1925 and later named Roy Fitzgerald, he was discovered by Henry Willson, the head of talent for Selznick Studios. The big-time and notoriously predatory agent groomed him into an everybody’s American, heterosexual movie star role (as he did with many other young gay men) and gave him the almost parodic hypermasculine name Rock Hudson. Talented director Stephen Kijak illuminates in his documentary the sharp contrast between Hudson’s private life as a decent, optimistic, ambitious, free, and kind man with Rock Hudson’s public persona. The director illustrates the dichotomy between them by intercutting out-of-context scenes from Hudson’s long career with a mix of photos and video clips, interviews with the star himself, loyal lovers, boyfriends and friends, historians, critics, directors, co-stars like Doris Day and Linda Evans, and Rock Hudson biographer Mark Griffin. It must have been an unimaginably big task for Kijak and editor Claire Didier to choose what material.

Those who might not have much knowledge of Rock Hudson’s filmography also get a movie history lesson. It took time for the studios to understand what to do with him. Before becoming a major movie star, the young actor was casted in over 25 films, mostly Western, adventures, military and action B-movies such as “Winchester 73” (1950), “The Desert Hawk” (1950) and “Iron Man” (1951) until Douglas Sirk saw some potential and put him in the comedy “Has Anybody Seen My Gal” (1952). In interviews, the director admits that Hudson wasn’t as good an actor as James Dean, who had a small appearance in the film, but the Prince Charming formula turned out to be a winning stroke – he was the sort of man a woman would long to bring home to her parents. Hudson became a huge money maker and megastar in stylized romance director Sirk’s “Magnificent Obsession” (1954) starring Jane Wyman, following with “All That Heaven Allows” (1955) and “Written On The Wind” (1956). With his signature style the German outsider Douglas Sirk, who inspired auteurs Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Pedro Almodóvar and Todd Haynes, poked holes in American values of the 50s to make the audience look underneath the surface. Under the beauty you’ll see the torrid reality. Considering Hudson’s own life, his big breakthrough as a star in Sirk’s films is even more staggering – a manufactured identity, playing the game and presenting a façade (he did tie the knot with Henry Willson’s secretary Phyllis Gates in an obviously arranged marriage).

Kijak continues exploring Hudson’s filmography reading between the lines of every performance with his private life. In “Giant” (1956), Elizabeth Taylor became his long-time soul mate and he paired with Doris Gay in genre-defining romantic comedy, and meta-film, “Pillow Talk” (1959) following with “Lover Come Back” (1961) and “Send Me No Flowers” (1964). We trail him during the peak years of movie stardom in 1950s and ‘60s to John Frankenheimer’s shocker “Seconds” (1966) to the TV-series “McMillan & Wife” (1971-77) up till his final role in evening soap opera sensation “Dynasty” (1984-85).

What makes the documentary unique is how it shows what made Hudson so magnetic, and the way it explores Hudson’s unexpectedly unapologetic life as a gay man. Numerous playmates tell their stories on how they met him, about parties and being invited to his home “The Castle”, a Spanish-Revival style estate in Beverly Hills. Although everybody in Hollywood knew, Hudson could slip away from much of the tabloids of the time, probably because he was one of the most bankable and likeable movie stars. Yet it left him perpetually at risk to blackmail and career ruin. In a time of witch hunt in Hollywood, during and after the McCarthy era, many hid their private identity, meaning a lot of sneaking around and acting.

In 1981, when the discovery of an inexplicable and fatal disease appeared ravaging many in the gay community, the Reagan administration (1981-89) chillingly chose to turn a blind eye, with no public response. Ironically, fellow actor Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy were supposedly good friends with Hudson, who attended a state dinner at the White House in 1984, the year before he passed. In one betrayal, Nancy Reagan declined Hudson’s request for help in getting specialized AIDS treatment in France in 1985. The reluctance of the federal government to intervene infuriated many and worsened the growing crisis.

The government was horrifyingly slow to increase research funding and not until September 1985 did President Reagan even first publicly mention AIDS while U.S. leaders remained largely silent for years. By now the tone in the documentary has changed. The disclosure that Hudson was dying of the disease at 59 in 1985, the first major celebrity, helped change public policy to more serious commitment and was a turning point on how the public viewed AIDS and perceived gay people. He made a difference to destigmatize and raise awareness, with longtime friend Elizabeth Taylor as one front ally.

With his buzzy documentary, initially titled “The Accidental Activist”, Kijak pulls the viewer into an important chapter in Hollywood’s movie and LGBTQ history by thoroughly exploring Rock Hudson’s hidden life. But also reminding those who might have forgotten, and enlightening newer generations about a movie star, who didn’t intend to, but became a cultural and political catalyst. Hollywood’s Adonis, “the personification of Americana”, leaves us to wonder how he emotionally handled his life and his carefully sculpted image. But then again, because he was considered a great performer in both movies and life, we may never really know.