Emily Brontë, along with her sisters Charlotte and Anne, was one of the most significant literary figures of the nineteenth century. Her innovative novel Wuthering Heights had a wide range of adaptations for the screen, since the early days of cinema.

The first adaptation of the 1847 publication goes back to 1920 and was directed by A.V. Bramble, starring Milton Rosmer (as Heathcliff) and Ann Trevor (as Catherine). It was primarily filmed in and around her home village of Haworth. It is not known whether the film currently survives, and it is considered to be a lost film.

Then came the 1939 romantic period drama film directed by William Wyler, produced by Samuel Goldwyn, starring Merle Oberon (as Catherine), Laurence Olivier (as Heathcliff), David Niven (as Edgar), Flora Robson (as Ellen Dean) and Geraldine Fitzgerald (as Isabella Linton). This version depicts only 16 of the novel’s 34 chapters, eliminating the second generation of characters. Rumors claimed that Olivier and Oberon reportedly loathed working together. Legend has it that when director William Wyler yelled “Cut!” after a particularly romantic scene, Oberon shouted back to Wyler about Olivier, “Tell him to stop spitting at me!”

Amongst the lesser known adaptations for BBC Television were the 1953 version, scripted by Nigel Kneale and directed by Rudolph Cartier, starring Richard Todd as Heathcliff and Yvonne Mitchell as Catherine. In the Land of Oz, in 1959, an Australian television play adapted this TV play under the direction of Alan Burke, and starred Lew Luton as Heathcliffe and Delia Williams as Cathy Earnshaw. In 1962, another BBC production used Kneale’s screenplay again and saw Rudolph Cartier at the helm of production, with Claire Bloom as Catherine and Keith Michell as Heathcliff. This picture has survived, although it is not available to the public. However in between these, another TV version might have struck the hearts and memories of audiences more effectively: the 1958 version directed by Daniel Petrie starring none other than Richard Burton as Heathcliff and Rosemary Harris as Catherine Earnshaw.

By the time we get to 1970 there is the film directed by Robert Fuest, with Anna Calder-Marshall (as Cathy), Timothy Dalton (as Heathcliff), Ian Ogilvy (as Edgar), and Judy Cornwell (as Nelly), Hilary Dwyer (as Isabella). Like the more renowned 1939 version, this film leaves out the latter part of the novel entirely, contrarily to the 1992 film directed by Peter Kosminsky that includes the oft-omitted second generation story of the children of Cathy, Hindley and Heathcliff. This movie marked Ralph Fiennes’s film debut as Heathcliff and starred Juliette Binoche (as Cathy), Simon Shepherd (as Edgar Linton), Sophie Ward (as Isabella Linton), Janet McTeer (as Nelly Dean). The peculiar trait of the film is that Juliette Binoche also played the role of Catherine Linton, the daughter of Catherine and Edgar.

Also beyond Anglophone countries the film industry was charmed by the Wuthering Heights phenomenon. The legendary director Luis Buñuel based his 1954 Mexican work Abismos de Pasión on the novel by Emily Brontë, as much as Jacques Rivette with his 1985 picture Hurlevent. In Asia, the country that produced most screen adaptions of Wuthering Heights so far has been India, with Arzoo in 1950, Hulchul in 1951, and Dil Diya Dard Liya in 1966. In 1983 there was the Pakistani Urdu-language adaptation Dehleez. Whilst the Philippines ventured into two adaptations with Hihintayin Kita sa Langit in 1991 and The Promise in 2007. Even Japan in the late Eighties had its own take on this story with the film Arashi ga oka directed by Yoshishige Yoshida, that was shown in competition at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival.

In the new millennium there were three more adaptions of Wuthering Heights before we get to the much coveted 2026 version. The 2009 two-part British ITV television series directed by Coky Giedroyc, starring Tom Hardy and Charlotte Riley in the roles of the lovers, who would eventually become a couple in real life; the 2011 film directed by Andrea Arnold starring Kaya Scodelario (as Catherine Earnshaw) and James Howson (as Heathcliff); in 2022 Bryan Ferriter directed the adaptation where he also played Heathcliff, next to Jet Jandreau who played Cathy.

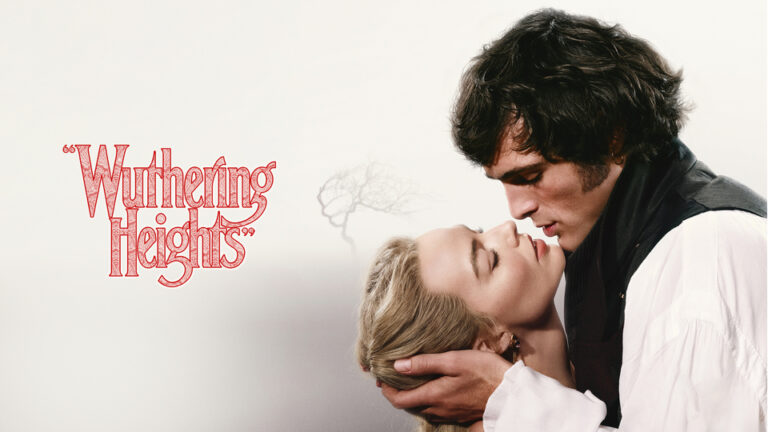

Therefore Emerald Fennell had to stand up against at least 20 screen adaptations, before newly representing this tale of tormented passion set in the Georgian era. She started this colossal enterprise by casting two of Hollywood’s most talented and cherished actors: Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi.

Leading up to the release date — that was strategically chosen for Valentine’s Day — all the media promotion focused on the incredible chemistry between the two actors that very much resembles the ‘showmance’ or ‘PRomance’ that is often crafted by production teams to create a buzz around a romantic film. For instance, in an interview, Robbie said: “I’m so codependent with people I work with and I think I developed that quite quickly with Jacob too.”

Codependent is a word that doesn’t seem to be chosen randomly, since many dysfunctional relationships (such as the one between Cathy and Heathcliff) use this term to define unhealthy partnerships. Further in line with the characters’ obsessiveness for one another, Robbie described how her co-star’s vicinity on set became addictive: “I found myself starting to look around to see where he was. When it turned he wasn’t watching I was really unnerved and unmoored. And I felt quite lost, like a kid without their blanket.”

Whether these remarks were a publicity stunt or not, Robbie’s Cathy and Elordi’s Heathcliff are incredibly sensual and catapulte viewers into what has been described as a fever dream. They embody a lustful magnetism that unites them through the excruciating enslavement of desire. Their carnal attraction is raw. But equally irrepressible is their emotional dependency, that digs its roots in their childhood.

In fact, much of the original storyline and characters have been changed, focusing only on the first generation. If in the novel and in all the adaptations the presence of Hindley Earnshaw, Catherine’s elder brother, was considered a necessary antagonist for Heathcliff, Fennell eliminates his presence and channels his drinking, gambling and abuse into Mr Earnshaw. This patriarch, played by Martin Clunes, is the stereotype of the father-master, that has no resemblance to the kind man of the novel, who had adopted Heathcliff and named him after a son he lost. In this film it is Cathy who names and shapes Heathcliff. She has the tendency to boss him around like Buttercup did with her Westley in Princess Bride.

But more than Mr Earnshaw, the character that has been transformed the most and forged into a determining adversary for the Heathcliff-Cathy romance is Nelly, played by Hong Chau. She was the main narrator of the novel, and a sort of foster-sister-servant to the young Earnshaws, and showed great sensitivity towards the inseparable bond between Cathy and Heathcliff. But Fennell, through a twist of events makes Nelly the responsible architect of their permanent separation.

As for the Lintons, Edgar is played by Shazad Latif and doesn’t seem to fully embody the charm of the literary character. But more than him, Isabella Linton is light years away from the original sweet and poised sister. In the film she has been transformed into a ward, and Alison Oliver portrays her as a grotesque ingénue, that seems to have popped out of a horror film.

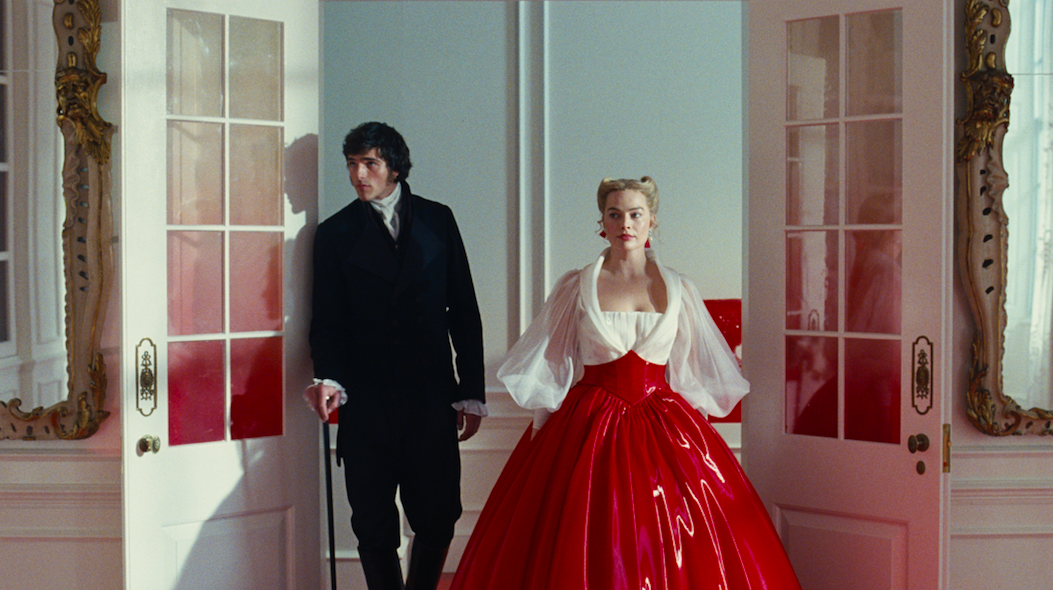

In terms of visuals, the motion picture is a bewitching feast for the eyes. There are many nods to the epic romances that have forged the history of cinema. In fact, many have noticed how this version of Wuthering Heights had certain frames and colour palettes evocative of Gone With The Wind. The director’s bold choices, paced to the sound of Charli xcx’s soundtrack, are extremely gripping and the editing by Victoria Boydell serves as the hook, line and sinker.

Costumes have also been a major topic of debate, because they are historically inaccurate. However, it turns out that the anachronistic approach adopted by costume designer Jacqueline Duran was intentional. She is the one who shaped the wardrobe of Margot Robbie in the film Barbie, and this time she dressed the actress in shades of red, black and white, with flamboyant forms and fabrics, to reflect Cathy’s all consuming passion for Heathcliff.

The same effect is obtained by the locations. The gothic setting embodies the dismal spiritual atmosphere of the windy moors, that mirror the unfortunate couple’s torment. Linus Sandgren’s cinematography is transcendentally intoxicating, whilst Suzie Davies’ production design is spellbinding and hypnotic.

When it comes to the narrative, the essence of the story is transmogrified. Emily Brontë’s novel did not describe a grand aspirational romance, but represented a strong critique to an all-consuming addictive partnership. Emerald Fennell ditches the toxic love approach to embrace a Romeo & Juliet romance, where conflict comes from the characters who are in proximity of the star-crossed lovers. Thus, Heathcliff is no longer a villain, but a romantic hero. He no longer manipulates Catherine first, then Isabella; he expresses openly every evil deed that will stem out of his frustration. In these regards, certain parts of dialogue spoon-feed audiences. If the beauty of Victorian literature was the subtext, here it is all spoken out loud, which feels very Gen Z.

Nevertheless, this shift of storytelling is praiseworthy for taking a distance from the continuous glorification of the rake archetype. Heathcliff here is an embittered good guy, whose ill-doing pales by comparison with the original character. As a matter of fact, we should question why society still awaits with trepidation for the portrayal of abusive partnerships. It is quite paradoxical how on one hand, series such as Bridgerton perpetuate the myth of taming the bad boy, and on the other, feminist activism tries to contrast this phenomenon — at times pointing the finger against the entire male gender without making any distinctions. The operatic intensity that continues to glorify this type of dynamic is detrimental for the pursuit of gender equality.

Be that as it may, Emerald Fennell does not condone twisted affairs, she uses them for social criticism. She had already confronted, in her feature debut Promising Young Woman, how women are often expected to cope with trauma and injustice in a patriarchal society, even though she approached it in a one-dimensional manner that weakened the overall morale. However, in Saltburn she effectively portrayed seduction as a power game to revert class discrimination.

In Wuthering Heights Fennell conveys all the themes that are dear to her, changing the perspective on what can be a destructive force in society. Her focus is neither Heathcliff’s unsociable moroseness and Cathy’s self-harming devotion, these are the outcome of the actions carried out by those who draw them apart.

Emerald Fennell rewrites the myth of Wuthering Heights for a 21st society affected by Schadenfreude. This German word — that describes the self-satisfaction that comes from learning of the troubles and suffering of others — is the true obsessive and destructive force of our century. We witness it with the villains who hinder the romance between Cathy and Heathcliff, who are not very different from the keyboard warriors who express their hatred and envy online, causing psychological damage to those they verbally attack.

Emerald Fennell carries out a profound social commentary disguised as a love story, that overwhelms with its maniac fury. This 2026 film is a visual and emotional storm about love, not just within a couple, but within a family and within a society.

Fennell has worn the hats of actress, producer and director. Her grand-sounding style has lead her to win numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, two BAFTA Awards, and nominations for three Primetime Emmy Awards and three Golden Globe Awards. The next award season will undoubtably take notice of her Wuthering Heights.

Final Grade: A

Photos credits: Photo Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures.

Check out more of Chiara’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.