The sci-fi genre is often defined by its absurdist nature, as many stories feature alien invaders taking over the planet of their choosing through military might. But the new film, Landscape with Invisible Hand, instead offers a unique, emotionally relatable insight into how people reacts to a slow-onset apocalypse. During that invasion, humanity’s everyday life is eventually rendered alien and obsolete by their invaders, who initially proclaim they could improve people’s lives.

The movie is based on the 2017 novel of the same name by M. T. (Matthew Tobin) Anderson. Cory Finley wrote and directed the screen adaptation, which was executive produced in part by Brad Pitt and Tiffany Haddish.

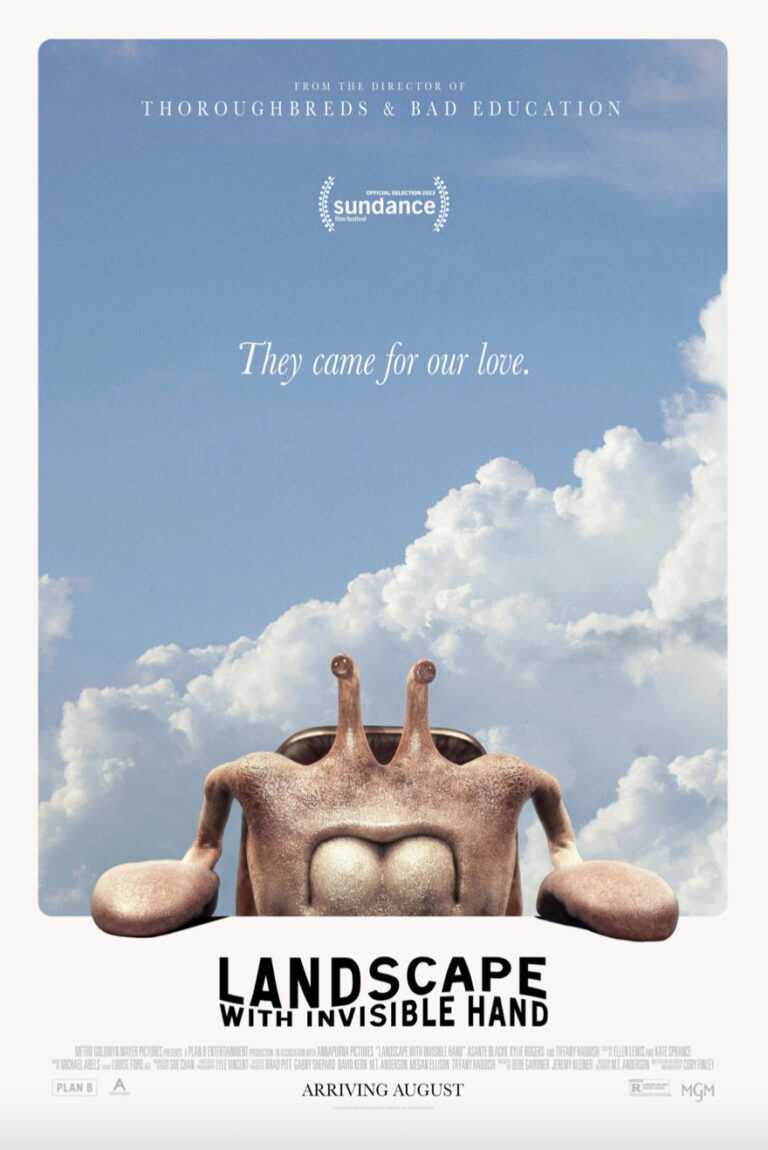

Set years into a benevolent alien occupation of Earth, Landscape with Invisible Hand chronicles how the human race is still adjusting to the new world order and its quirky coffee table-sized overlords called the Vuvv. Their flashy advanced technology initially held promise for global prosperity, but rendered most human jobs – and steady income – obsolete.

During the invasion, 17-year-old artist Adam Campbell (Asante Blackk) and his new girlfriend, Chloe Marsh (Kylie Rogers), discover the Vuvv are particularly fascinated with human love and will pay for access to it. As a result, the teens decide to livestream their budding romance to make extra cash for themselves and their families.

Life is good for a while, until the flame of their teenage love fizzles out. As a result, they’re forced to make life-altering sacrifices for their families, including Adam’s mom and sister, Beth and Natalie (Haddish and Brooklynn MacKinzie), and Chloe’s dad and brother (Josh Hamilton and Michael Gandolfini).

Finley generously took the time earlier this week to attend a special screening of Landscape with Invisible Hand at AMC Lincoln Square in New York City. The scribe-helmer participated in a post-screening Q&A to discuss the making of the sci-fi comedy-drama.

Q: The film is based on a book by by M. T. Anderson. How did you envision the story on screen?

CF: First, I want to acknowledge the wonderful M. T. Anderson, who’s here in the crowd. [Audience applauds.] As soon as I read the book, I loved many things about it. It’s this wild twist on the alien invasion premise. The book has this free market economic invasion, which I thought was really fresh and unique.

I also loved that it felt very hard to film in an exciting way. At times, the prose is wonderfully spare and suggestive, and it’s all narrated by the Adam character. It has this world-weary tone, as he has no sense of wonderment about this alien invasion, as it’s the crappy world he’s grown up in.

There are evocative, minimalist descriptions of the Vuvv. We learn little details, like the fact that they’re the size and shape of coffee tables. We also learn that they communicate in a way that sounds like someone walking vigorously in corduroys. I also love how the book enlisted the reader in the project of visualizing these crazy creatures.

I’ve done more naturalistic, people talking in rooms kind of movies in the past, so I was excited to take on a real visual challenge. The process of adapting the book was a real joy, and Tobin was a wonderful collaborator and person to speak with about his vision for the book.

Q: You include some of Adam’s art in the movie. How did you see his art in conversation with the visual language of the film, and where did you start with that?

CF: The design of the Vuvv was one huge visual component of the movie. The other was going to be Adam’s art. Having a visual element that wasn’t just a sci-fi spectacle felt very important in a film that was all about humanness, and holding on to what makes us human.

I worked with my production designer, Sue Chan, to think about how we would handle that challenge. We decided that we wanted to find a visual working artist who had their own style, and was excited about the task of adapting their own style into a character’s voice. We also wanted someone who had spent years refining their own way of making art. During that process, we found this amazing Atlanta-based artist named William Downs.

I didn’t initially conceive of the title cards, and they weren’t in the script. They were, in a sense, in Tobin’s book, as the book has these wonderful chapter titles that are named in a way of a painting, drawing or sculpture. So they kind of informed the title cards in the film.

We eventually realized that the story needed a free-flowing, not a hero’s journey, three act structure. So it then felt right to use that artwork to heighten the chapterish nature of the film’s story.

Q: You mentioned the other visual challenge was the Vuvv. Can you talk about envisioning them and the process of making them?

CF: Yes, that was the main part of the long, extensive pre-production. With COVID delays – which shows you how long ago we started working on this movie – after the first round of COVID hit while we were developing the Vuvv, Erik De Boer, the visual effects supervisor, and I started very early on. We tried to make a creature that was true to the strange, evocative descriptions in the book.

The other challenge we gave ourselves was that we didn’t want people to see the movie and go, “Okay, this is like a squid alien or a dog alien.” If anything, we wanted them to look like a coffee table alien, which is how they’re described in the book. We wanted them to not feel like the depictions of aliens we’ve seen in movies before.

The other key aspect of that design, which started almost as early as my work with Erik, was my work with Gene Park, the film’s sound designer and supervising sound editor, who I also believe is here tonight. We actually went about it a little bit backward, as Erik would design the VFX creature work first. Then the very last thing he would do was hand it over to sound and figure out how the Vuvv would roar and how their claws would sound.

But we thought, these really are characters who have speaking roles, essentially. We also knew that they needed to look and sound compelling when they were sitting behind a desk.

So Gene did some amazing trial and error work, and we worked together closely to figure out this sound that didn’t feel generic within the science-fiction genre. We wanted sounds that felt grounded, but didn’t sound like a version of a roar or bark.

Q: You mentioned these science-fiction sounds. Can you talk a little bit about Michael Abels’ score, and how you saw that functioning in conjunction with the way the Vuvv are speaking?

CF: Sure. Michael Abels’ score is one of my favorite parts of the movie as a viewer. This was the first time that I had the pleasure of working with a composer from the beginning of the process. Before he even saw any footage from the movie, Michael started playing around, just based on reading the script and talking about the tone of the movie.

He found an interesting use of the theremin, a very early electronic instrument. It’s often used as just a side effect, but he used it in a very romantic way. He also put in strings and piano that you don’t often associate with the theremin. He’s a brilliant guy, and brought such an important aspect of the emotional role to the movie.

Q: Can you also talk a little bit about the casting, especially in finding your Adam and Chloe in Asante and Kylie, and also building the families around them?

CF: Totally. It all kind of started with Tiffany, who’s someone I wanted to work with since I saw Girls Trip many years ago. Every once in awhile, regardless of the genre of the movie, and how far away or close to the movies you do, you see a performance that is electric in the way that that one was.

So I just made a mental note that I wanted to work with her as soon as I could find an opportunity. She was awesome in this process.

I had seen Asante in When They See Us, Ava DuVernay’s really awesome Netflix limited series, in which he played a very serious role. He was younger at the time, but he just has such a vulnerability.

When I met with him, he had grown up a bit since that time. But he had a mix of qualities that was needed for this role, including having an adult’s concern of having authenticity, while also having this youth and vulnerability. He’s such an amazing actor in so many ways.

The same was true with Kylie, who was in Beau Is Afraid. She had a very different role in that movie. But like Asante, she had that same mix of toughness and vulnerability that was needed for her character of Chloe in this film.

Q: Speaking of the vulnerability, the movie has a mix of melancholy and comedy. How did you find that middle ground?

CF: As a writer-director and an audience member, I’m really drawn to movies that have tones that are hard to pin down. I think agents prefer if you stick to one clear category, but I’m always drawn to stuff that is in the hard-to-sustain middle. I’m drawn to that tight-rope act of trying to hold together two or three different tones.

I don’t know if we had any thought-out strategy in doing this. But when we were in doubt, we just went back to the book, which has this sense of deep sadness and extreme ridiculousness, which is the best kind. The movie kind of brings those two things together and let them play off of each other, rather than trying to smooth them out.

Q: You mentioned earlier that you feel in love with the alien economic invasion idea, which feels pertinent now in almost all ways. How did you want to thread the economic realities of modern society into the film’s narrative?

CF: Again, that’s what’s really unique about the book. It’s not an alien invasion movie in which the heroes pick up a gun and lead a rebellion against the aliens.

I guess the narrative challenge in that related to the earlier question about the chapter titles. When you’re telling a story about conquerors who have taken over the world through the markets and making products better and cheaper than humans do, it doesn’t lend itself naturally to that heroes’ journey.

So we tried to find a way to embrace that and make it a bit more naturalistic, and make the episodic work more compelling. We tried to make it more true to the underlying proposal of this world.

Q: We’ve spoken a bit about the production design in the movie. How did you create the world of the Vuvv?

CF: That was fun. There were many learning curves for me, and the big one was probably the visual effects work. The other was the amount of world building that landed in the hands of the production design department, essentially.

So we had a really long prep, which allowed me to work with Sue Chan, our production designer, who I mentioned earlier, and do a lot of storytelling work. That work doesn’t get covered in the screenplay, so we could draw on some elements that are in the book.

We tried to answer all kinds of questions, like what would the signs look like in this particular world, and what architectural struggles the Vuvv would draw upon. We also asked, what human media are they consuming, and that was very fun. That was a new process for me.

Q: Speaking about the human media that the Vuvv are consuming, Adam and Chloe broadcast their love story and put on a show for them. How did you find the teenage love story within the film?

CF: One of the delightful things about the book is there’s even more of this thread of mid-20th century influence on the Vuvv. There’s an idea that the Vuvv started watching the humans around the 1950s. So they have a fixed idea in their heads of that being the golden age of human existence, in a colonialist, tourist kind of way. We wanted that to inform the rest of the movie’s story.

AI has become more of a hot-button concern in the time that we’ve made this movie, which is fascinating to watch. I’m always interested in, and horrified by, the idea that if you train a language model on human behavior, it will pick up and reproduce some of the problems communicated in our society.

So I thought it would be interesting if these emotionless, bureaucratic creatures landed on Earth and started studying humans. It would also be interesting to see if they latched onto some of the sins of human history and the horrible ways we’ve treated one another over the years.

In terms of humans finding their first awkward infatuation, that was always a thing that attracted me to the story. Placing this early teenage courtship in a commercialized world, where love is the last commodity that humans can sell, as these aliens have taken away all of their jobs, was really compelling.

This was probably the first time that I shot scenes of genuine, pure, sweet first love. As a director, that was one of the things that I was most nervous about – not being able to rely on irony, darkness and deadpan humor.

These actors had to really connect, and make it feel as though there’s a real vulnerability there. Some of those sweeter moments were the very last things that we shot, and the whole cast was very comfortable with one another by the end of the shoot. So it was great to see how much genuine emotion they brought to those scenes.

Landscape with Invisible Hand is now playing in theaters, courtesy of MGM.

Check out more of Karen Benardello’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.