Synopsis : Maestro is a towering and fearless love story chronicling the lifelong relationship between Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein. A love letter to life and art, Maestro at its core is an emotionally epic portrayal of family and love.

Rating: R (Some Language and Drug Use)

Genre: Biography, Drama, Romance, Music, Lgbtq+

Original Language: English

Director: Bradley Cooper

Writer: Josh Singer, Bradley Cooper

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Release Date (Streaming):

Runtime:

Distributor: Netflix

Production Co: Netflix, Fred Berner Films, Sikelia Productions, Amblin Entertainment, Joint Effort

Press conference for Bradley Cooper’s Leonard Berstein biopic Maestro, screenwriter Josh Singer, producer Kristie Macosko Krieger, Leonard Bernstein’s daughter Jamie Bernstein, makeup designer Kazu Hiro, costume designer Mark Bridges, production designer Kevin Thompson, production sound mixer Steve Morrow, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin, the conducting consultant and conductor for new recordings and Music Director of The Metropolitan Opera join NYFF Spotlight Programmer Justin Chang

Q: What brought you into this? Can you talk about your collaboration with co-writing with Bradley?

Josh Singer: Nine years ago, Fred Berger and Amy Durning, the original producers on the project, approached me to tell the story about Leonard Bernstein. Marty Scorsese that was attached to direct. As a nice Jewish boy who grew up singing in the synagogue choir with a real love of music and specifically, music with some Judaism laced through it, I was attracted to the project. I spent two or three years wandering in the desert doing research and talking to the family a little bit.They introduced me to some wonderful people that knew Lenny.

I gleaned what I could and put together a script that managed to attract Steven [Spielberg] and Kristie [Macosko Krieger]’s attention. I worked with them on “The Post” and then managed to attract Bradley’s attention through Kristie. I heard words that no screenwriter wants to hear, which is “page one’ — a page one rewrite. The script was clearly going to be shelved because Bradley would rather go in a different direction and normally, in those situations, the writer is shelved as well. But fortune smiled upon me; Bradley asked if I would join him in this adventure as I had already done research. I was thrilled.

When you have Bradley Cooper joining your movie as a writer, you don’t know what to expect. He’s a great actor and director but is he going to get into the muck? I certainly found that he gets into the muck, but he was going to go so deep that I was struggling to keep up, which is not something I’m used to doing. Bradley read everything that I had read and more. Bradley talked to everyone I had talked to and watched all the video there was.

There’s Johnny Gruen’s book about the family in which he spent three months in Italy — in 1968 or 69. That book became a touchstone in part because it was this really wonderful insight into the family, which was clearly Bradley’s focus. But he also had these wonderful audiotapes where Gruen spent [time] talking to all of you guys, which Bradley listened to ad nauseam, so much so that he used to be able to write stuff. I’d be like, “Oh, which book did you get that from?” And he’d be like, “No. I just wrote that.” He literally could channel Lenny in that way.”

@Josh Singer

@Josh Singer

Q: From your perspective, what was it like navigating these moving parts and bringing Bradley on board, first to star in?

Josh Singer: When it became clear that Steven wasn’t going to direct it, Bradley said, “I just made this movie called “The Star Is Born.” It had not come out yet, and he said, “Would you guys be willing to come watch it?” So Steven, Kate Capshaw and I all went to watch the film and in 20 minutes, Steven leaned over to Bradley and he was like “You’re directing this movie.” Anyway, we signed him on to direct and star and then we got the blessing of the family. We were sort of off to the races. Bradley goes deep in research, he went to every department head and he really worked closely with everyone.

It was all in the prep work for him. We worked for 3.5 years honing everything, getting it right, getting the makeup right and working with Mark Bridges to find the right costumes, and working with Kevin [Thompson, the production designer], figuring out the right set. We were building the locations, but we wanted to go to the hallowed grounds where Lenny and Felicia lived. Bradley really wanted to make this movie authentic. For me, it was easy to get on board when the director was so passionate about everything he was doing. He showed me what he was doing. We did a screen test, we did a film test on hair and makeup and we really went to great lengths to prep with those when we got on location.

Q: Jamie [Bernstein], there’s been an interest in making a Bernstein movie over the years. What was it about the script, and this creative team, that allowed you and your family to trust them, not only with your father’s story, but, as we can see, that this is equally your mother’s story as well.

Jamie Bernstein: I will tell you, it was Bradley’s own idea. The original notion of this project when it was first thought of about 15 years ago was that it would be more of a conventional biopic film. Then, Bradley suggested that his approach would be different. He preferred to make it an exploration of Lenny and Felicia, more of a portrait of a marriage. My brother, sister and I were so impressed and pleased with that idea and that angle, that lens through which to tell the story, from the very beginning of Bradley’s arrival on the project, we felt like we were in unusually good hands.

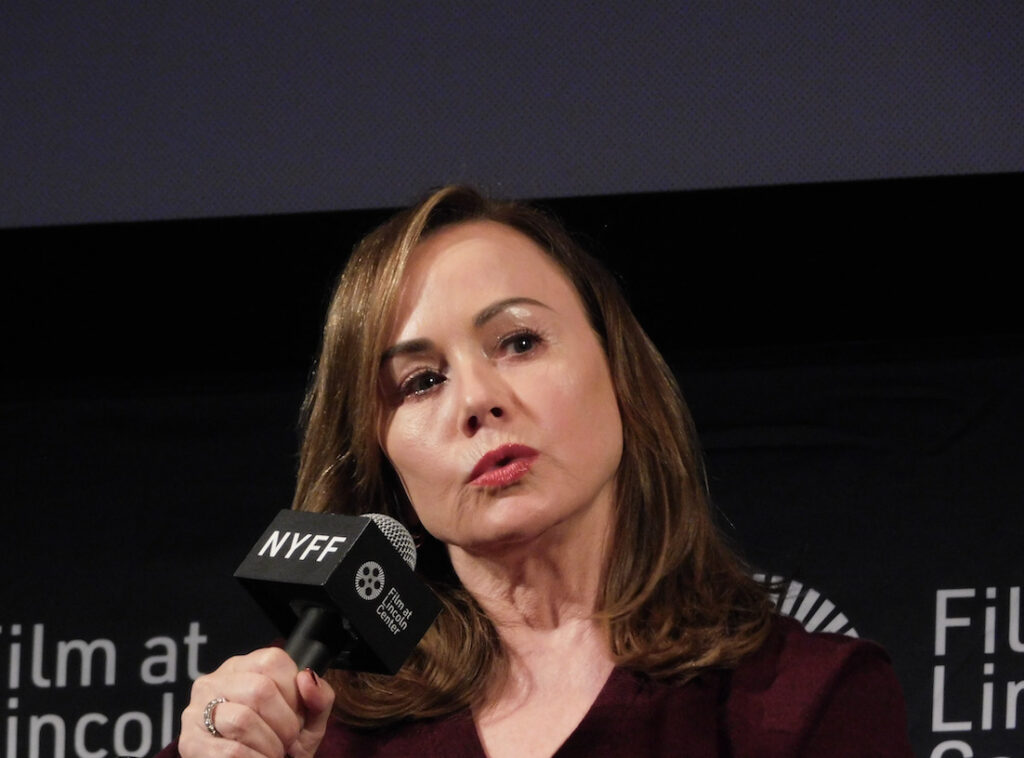

@Kristie Macosko Krieger

@Kristie Macosko Krieger

Q: Everyone must have spent their time with Bradley. You [Kazu Hiro] spent maybe the most time with him, with the hours of makeup application and everything. Talk about the process of aging him. The movie starts with him towards the end of his life. Talk about the decisions that you made going into that.

Kazu Hiro: Lenny was at his oldest stage when I saw him on TV when I was young. I was really inspired by him and loved his look because he was such an iconic person, so filled with a passion for music. It shows through and so that time was like 35 years ago, I thought that I wanted to work on the film about him and finally, it came true. I love his work. So at first, the first test makeup we did with Bradley was middle stage. That’s because the artist at the middle stage is the most featured in the film.

When people get older, what happens is not added on the surface; it’s more like a kind of strength and that’s the age when it happens. The only thing we can do is add on the surface. We have to figure out what would be the best way to convincingly make a further look like then. At the same time, they became older. That was the point. We went through a lot of detail — there’s more elements to add on. He had a really big suit so we had to add — it also changes and as he aged, we pinch in the lobes.

Jamie Bernstein: I was so impressed with how you were able to recreate my father’s ear.

Kazu Hiro: We made a nose because he wanted to talk like Lenny. The first thing he asked me, “Can you make a nose that would change my voice?” I made him a different nose, to give him a more nasal voice and so, as he gets older, Lenny’s nose was made wider to shape his voice. Usually, the makeup department has more time to stay until the filming is ready, because Bradley had to direct as well as star.

Q: Mark, your costumes are remarkable and captured his progression over the decades so well. Having two characters who were so very beautiful, very stylish people, what were the challenges and pleasures in dressing the Bernsteins throughout the film.

Mark Bridges: We were always trying to tell a story. We had to do a 40-year passage of time, the ups and downs of their lives, the different social circles they ran in. Figuring that out, we had a lot of visual references of a well-documented life. But that’s where the imagination comes in — you find an amazing piece that you could go for each period. We worked very closely with Bradley. He was tireless in coming to fittings. He gave me three hours on Tuesday, three more on Wednesday and three more on Thursday.

He was dedicated to those fittings. We really worked very hard. Carey [Mulligan] was a real joy to work with because her acting process is such [that she] gives an outside shell to their inner life. It was incredibly exciting to work with an actress like Carey and figure these things out. I do research. There’s a great biography about Leonard; and of course, [there’s] Jamie’s [2018] book, “Famous Father Girl.” [I’m] reading this and taking flights of imagination, but also reading between the lines on what this is and what it could be in terms of clothes.

@Jamie Bernstein

@Jamie Bernstein

Q: There’s such a rich photo record for inspiration. Were there any distinctive signature outfits or touches that you were especially pleased to incorporate?

Mark Bridges: One of our favorites is a costume that was taken in 1976 I think. It’s a small period of Leonard’s life where he had a beard. It was really striking with the neckerchief and was perfect for that moment because it echoed what he was saying verbally. There’s a color photograph and it’s perfect for that moment in the film. Why not use it? Bradley, jokingly, called it his “Pirates of Penzance” look. We really got a kick out of that — that was the meeting of research and appropriateness for the script and for a director and actor all happening at one time. That’s one of our favorite costumes.

Q: Kevin, two of the film’s most important locations, of course, are the Bernstein family [homes]. There’s an apartment on the west side which had to be recreated. And their Connecticut home, which you were able to shoot in, the actual [locations]. They’re both so seamlessly done, but they’re two very different challenges — please speak about the decisions that went into restoring that place.

Kevin Thompson: The intimacy of their domestic life was really critical to get into the background of what their characters were like and what kind of people they hung out with, but also their private life in the country and how that intersected with the other. The Bernsteins opened up their country house that was filled with memorabilia and scrapbooks.

We could get into that amazing research — Felicia’s paintings, things on the walls and snapshots around that led us to understand the depth of their relationship and what kind of life they had and from the games they played and things like that. That led to an understanding of how to detail their life in the city with the activities that went on — especially in their legendary Dakota apartment that you mentioned. We were lucky enough to get into the actual apartment so we could scale duplicate moldings and get the feeling right.

Then we added the layers of all the things that represented their style and their lifestyle with the parties, the Thanksgiving dinner and things like that. You get technical stuff from the periods, but Bradley was always like, “Come back to the center of understanding what is the emotional story that we’re telling. Always go back to that as a touchstone, what is the scene saying?” That was always the non-tangible thing that you try to inject into the design as you were going.

@Steve Morrow

@Steve Morrow

Q: In the earlier part of the film, the formal playfulness of the sets in that first half — in black and white — is striking. When we see his bedroom with this curtain that looks like a theater curtain and then bleeding into the hallway and morphing into the balcony of Carnegie Hall, it was such a kind of joy to see. Talk about that physical movement between on- and off stage.

Kevin Thompson: That set was modeled after the actual Carnegie Hall artist studios that were on the top floors of Carnegie Hall that housed musicians and artists. We modeled it after the slope of the skylights that exist now. It was very complex because of that camera move, that single shot. We went through many incarnations and fine-tuned the angle of the ceilings, which pieces were going to fly, the elaborate crane shot so that we could do it practically to go out in the hallway and actually into the top tier box of Carnegie Hall. It was pretty much what Bradley conceived of in one of our first meetings together. It went through many incarnations, but I think he got the production he originally had in his head.

Q: Steve, this is a movie in which music plays such a [vital] role. Obviously, it has to sound extraordinary and it does. You’re no stranger to mixing sound on musical films with “La La Land” and working with Bradley on “A Star Is Born.” You already have a collaborative relationship with him, so what were some of the fresh challenges and goals sound-wise on a movie like this?

Steve Morrow: He and I have an understanding that if there’s something on camera that’s being played or being sung, he wants it to be live — that way that the audience can be much more connected with the material versus us trying to fake it. The goal was always we’re going to do this movie about Leonard Bernstein and he’s going to conduct and we will have orchestras and choirs and we want to do that live. The technical challenge is to make sure that we can record it in a way that nobody is used to hearing it.

We’re all used to hearing classical music on the radio, or even in movies, but the way that you can get the audience in the middle of an orchestra, to feel the feeling that he must have felt or that the players must have felt, that was always the goal to be as authentic and immersive as possible. A lot of discussions for years were on what was going to be live and what wasn’t. It turned out that pretty much anything on camera is being played live.

A little bit of sleep was lost on that, but we were able to figure it out. It was always important to him that conversations and the arguments or dialogue always felt natural, like people would talk over each other sometimes and that was OK. It was always a careful dance of what his desire was and what you wanted to hear. Some of the big party scenes with all the extras talking, everybody was talking and you’re able to do that in a technical way if you know in advance, that’s what we’re going to go through. Bradley and I had many discussions about that, having it feel real, automatic and have the actors talk over [each other] in the party scenes. That’s why it feels that way because it was that way.

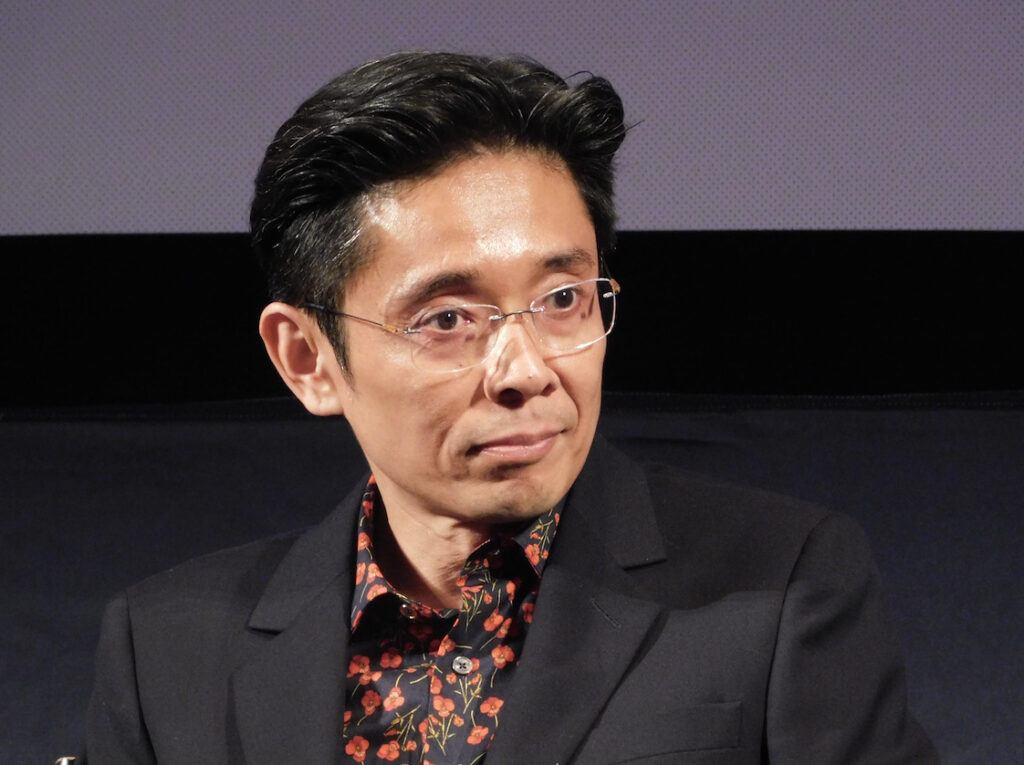

@Kazu Hiro

@Kazu Hiro

Q: Yannick, you essentially trained Bradley in the art of conducting — a crash course as it were. Were there common assumptions, misunderstandings about what a conductor does and how they do it that you wanted to correct? What was the experience like training Bradley?

Yannick Nezet-Seguin: Well, to begin with, conducting is a very, very mysterious craft. I don’t know if us conductors know exactly what we are doing anyway. No, we know what we’re doing, but what I mean is that we don’t know exactly which gestures we’re doing because the thing is that there are common things that every conductor learn and I could probably teach this entire room in about five minutes but it mostly has to do with the right hand which holds the baton. This is international to every conductor, but the rest of it is all different because we have to embody the music.

So, bring in Leonard Bernstein, one of the most documented figures of classical music and conducting. I would say, probably the most influential conductor and influential musician by far. He was a trailblazer at not being afraid of showing emotion on the podium. Before him, there was a lot of this kind of traffic cop thing; you just stay there. You make sure everyone is together. For Bernstein, it was all about living the music with everything in his body. I think Bradley, because he is a fabulous actor and, as has been mentioned seven times now, his research is incredible, relentless, fantastic — so detailed and deep.

He came to me, knowing the mimics, knowing the shoulders, knowing all of that. But how do you make it believable so that he can conduct the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in Mahler’s second symphony — which is notoriously one of the most difficult moments for a professional conductor, let alone someone who is not a conductor. My goal was to actually start from scratch but we didn’t start from scratch.

“Oh, let’s have a go at how conducting goes.” If I were to take him where he was and then give him some technical assurance would leave him free to be Leonard Bernstein as an actor, which is an emotional event, I would describe it, because it would have been such a mistake in the movie that if you portray Bernstein as a conductor and it looks like a school band — no offense to school band conductors. We need those. but it’s not exactly who Lenny was. We found ways for being in preparation and on locations to let him be free to express while still really being able to do 1234 at the right place because it does indeed drive us crazy classical musicians when we see out here that’s like 1212. No, it’s the other way around it buddy. That was important.

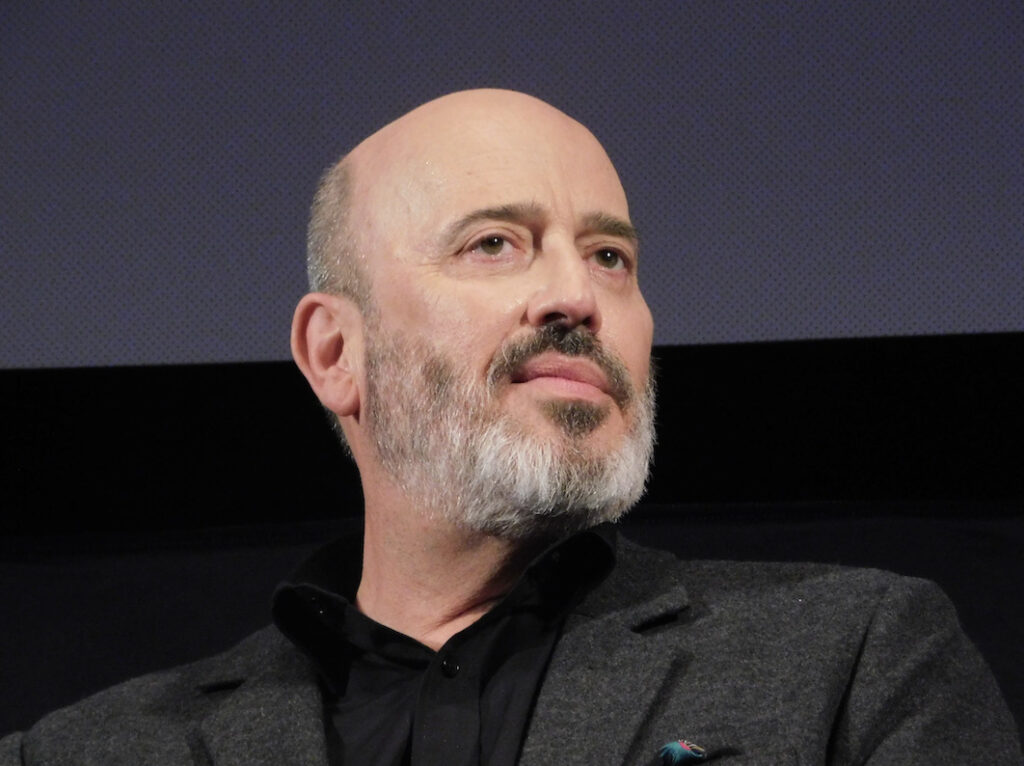

@Yannick Nézet-Séguin

@Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Q: The scene at the end where he is teaching a student, basically you are Bradley teaching as Bernstein teaching this young conducting student who has to be good, but is a little bit off. Can you talk about putting that together?

Yannick Nezet-Seguin: I’m glad you bring this up because, as a conducting consultant, my work was especially with Bradley of course. I also had to coach this fabulous actor, Jordan Dobson, who was playing William, who’s an actor, not a conductor. It has to be believable that this person is talented, but not quite. There were some ways to do that. And, not to reveal too many secrets, but that scene was the first we shot together, the very first day for me on set. We had to talk about all the aspects at once.

The teaching of how effortlessly, at that moment, Lenny could take and show what he wanted the young conductor to do, but like an older conductor, they don’t have to do a lot. Everybody understands and then you get the other young conductor who’s tripping over the music style because when we’re young, we want to do it all at once. I still want to do this even though I’m not that young. It was a fascinating thing and I’m so glad that this scene is there because Lenny, the teacher, is maybe one of the things that makes, to this day, Leonard Bernstein such an important figure in music.

Q: The costumes for Felicia are so nuanced and beautiful and at the same time, they’re often the signifier of the decade they are in.

Mark Bridges: They’re tied to the decade so that it was very important to keep the audience in tune with the passage of time. When we’re telling the story, we need to understand that they are in the 40s and are still in love and connected during the 50s when he runs backstage and needs his touchstone during breaking and conducting. Then when we go to the 70s, your understanding is that developments are happening in the relationship as well as in the fashion [of the time]. The fashion is changing and the people are changing within themselves as well. Hopefully you see a color palette change, a hem-length change and that helps the story along and connects the audience with that passage of time.

@Kevin Thompson

@Kevin Thompson

Q: Mr Singer, how spontaneous was everything? How did you create this room for moments of spontaneity or room for improvisation? How, how did you work with Bradley about those moments?

Josh Singer: You’re asking about if there was a lot of spontaneity. It feels like a good bit of improvisation. That’s where I think Brad would be able to better answer that once, God willing, we have a settlement and they get what they deserve. But, for the meantime, [I’ll answer.] Bradley and I workshopped the script at the time. One of the things we did all the time was read back and forth, which I’ve never done before, and was extraordinary. You hear things that you don’t feel the same way when you’re just sitting and trying to re-read on your computer.

That process was just incredible. We were fine. We found that we had larger read throughs. At the end of the day, what you’re building in the script is a foundation, In a movie like this, what’s wonderful when you’re working with your director, who’s also your lead actor, is that he was deeper than I was into understanding the character and the dynamics as has been discussed of that marriage— that’s our central point, that marriage.

I believe he brought Carey with him so that they both knew Lenny and Felicia so well that they were able to improvise on the day. Often, you’re using the script as a foundation but then going into something that would feel even more natural. My favorite scenes and pieces are not the ones that were purely scripted, but are the ones where there’s a real balance between what was on the page and that natural organic improvisation which makes it feel spontaneous.

Q: Jamie, What was it like to see the final version of the film? Did you see anything heartwarming for me to see?

Jamie Bernstein: Bradley was so generous about including my brother and sister and me on his own journey with this film, something he didn’t have to do. He could have just gone off once he had the license. Once we gave him permission to make the film, he could have just gone off and done it and never consulted with us again. Instead he made us part of his own journey. We saw so much [of it] being developed; he sent us pictures on his phone and showed us some little assemblies of footage. We were really watching the film coming together and saw several iterations of what was close to the final version of the film. For us, it’s been an enormous journey as well.

Seeing it in Geffen Hall, the very hall where we watched our dad conduct hundreds of times as we were growing up, was so gratifying and had such an almost mystical circularity for our lives which we shared with the three of us together and with our parents. Seeing the final version on that giant screen with the incredible Dolby Atmos sound was just overwhelmingly thrilling and also very surreal. Of course, all the way along, it’s been surreal to see these two people becoming more and more like our own parents but at different ages. Sometimes they’re older than we are now and sometimes they’re way younger. Sometimes we are the kids and it’s just, as you can imagine, like having a very strange dream where you’re in your house. But it’s sort of not your house and you’re with your parents, but they’re, sort of, not your parents… But they are. It has that dreamlike quality for us. What a ride!

@Mark Bridge

@Mark Bridge

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles

Here’s the trailer of the film.