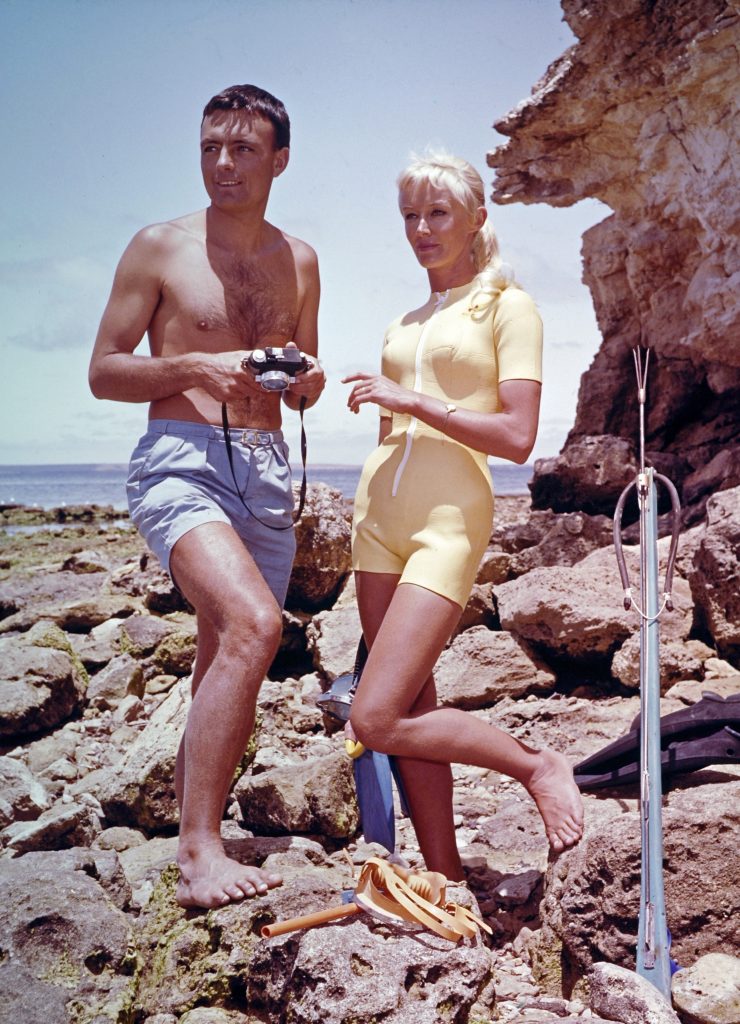

A true pioneer in both underwater filmmaking and shark research, Valerie Taylor is a living legend and an icon in the underwater world whose life’s work has become the basis for much of what we know about sharks today. Through remarkable underwater archival footage, along with interviews with Valerie herself, “Playing with Sharks,” from twice Emmy-nominated director Sally Aitken, follows this daring ocean explorer’s trajectory from champion spearfisher to passionate shark protector. From the birth of cage diving to “Jaws” hysteria to the dawn of cageless shark diving, Valerie became a trailblazing advocate for the ocean’s most maligned and misunderstood creatures.

An Exclusive Interview with Pioneer Scuba Diver Valerie Taylor, Director Sally Aitken, Producer Bettina Dalton

(Q) : A few years ago, we saw the Jane Goodall documentary. Why did it take so long to make a Valerie film? It’s so obvious that we had to make one.

Bettina Dalton: That’s so funny that you say that because I’m not sure if you realize, but it was that moment watching the Jane Goodall film that it struck me, I have to do a film on Valerie, and like you, I had the same reaction, or at least Valerie had the same reaction, which was, what took you so long? It was so obvious! But here we are, and maybe it was just the right time. Somehow I feel it was the right time for a film like this. We’ve all been through a lot of difficulty with the Covid and I think it’s making people reassess their relationship to nature and the natural world. I wouldn’t have had Sally if it was any other time, and we had the opportunity to scan the footage to this beautiful, pristine celluloid quality. I do sometimes think I should have got on with it sooner, but it is the right time, and I think the audience and people at festivals that have seen the film have responded in a way that reinforces that.

(Q) : Valerie, you contracted polio when you were twelve years old and isolated from your family. What was that like?

Valerie Taylor: It was horrible. I wanted my mother. I was in pain. Huge pain. And I was shut away in a big room with a lot of other people who were in pain as well. Men, women and children, all the babies died, every one of them. None of them survived. I think that’s why it was called infantine paralysis. It took me a long time. I couldn’t leave the hospital till I could walk. I decided I was going to walk, and I did. I had to be allowed to walk out. That was what I had to do, and I walked out. Then the government sent myself to a farm, sent all of the juvenile polio victims to farms around New Zealand to be built up again. When you’re very sick like that, you lose a lot of weight, you’re very thin. It also had an upside. I was sent many books by a religious group called the Brethren. They weren’t Christian books, they weren’t about the Bible. They were about adventure and I read them over and over again, and I remember that all I could think was that, when I get out of here, I’m going to have adventures. And I did. I really did.

(Q) : So once you were better, you went spearfishing. When you stopped spearfishing and decided to pick up the camera, what was the most significant reason that you made that decision and transition?

Valerie Taylor : Well, I was just with my husband, really. We had just won the Australian titles again. and right at the top of our trade, we were standing there, Ron and I, looking at all those hundreds and hundreds of beautiful dead fish waiting to be weighed in, and Ron said, I’m never going to do this again. And I said, I don’t want to do it anymore either. We were looking at creatures, wild animals that we had gotten to know, and realized they were just like wild animals on land, like a pack of dogs that are all different but they all had personalities. We had both won the Australian title, me the women’s, Ron the men’s, and we walked away at the top of our trade and we never did it again. For me, a spearfishing person, it was actually a good thing for what I was about to do and what Ron was about to do. We knew the animals we were protecting or wanted to protect. We had first-hand experience with them. We understood that they all had different personalities, and it made it very easy to walk away.

Ron said, I’m only going to shoot fish with my camera from now on. That’s what he did. We stopped spearfishing. Simple as that. We weren’t popular with the spearfishing community, of course. Because suddenly we were against them. We were conservationists. But I’m happy we did it. I’m proud we did it. And it wasn’t because we were cranky or because no one liked us or anything. My husband was the best in the world. He was as good as they get. We became conservationists, me in particular, and I worked out very quickly how to get the story across. You use the media always, if you see something bad happening, like a beautiful, big fish being slaughtered for sport or fun. You can’t eat it, all you can do is kill it and watch it die. Just watch it float away in the current. You get a good story. You get it on film and you don’t ever exaggerate or include an incorrect piece of information. You go on television, and eighty times out of a hundred, the opposition will attack, and claim you don’t know what you’re talking about. And you’ve got to, because Ron and I had all this experience to draw upon. And not only that – we had it on film. That made our efforts much easier than just going on there and talking about an animal that you didn’t know. I talked about creatures that I knew.

(Q) : When your friend Rodney Fox was attacked by a shark and got more than 400 stitches, a regular person might refrain from diving, but instead, you went back down and captured more shark footage. I’m surprised that you had so much courage to go back down and do that.

Valerie Taylor : I think Ron and I knew sharks very well. We knew that they’re not interested in eating humans, but they are very curious, like all animals. They have a curiosity. They don’t have hands to feel, they feel with their teeth. For Rodney, he was spearfishing. He had speared several fish. There was blood in the water. The heartbeat of a dying fish and nitrogen for sharks, they clean up this sort of thing. And the shark came in and it grabbed Rodney. It let go and it took the fish. He was fortunate that he was right near the safety boat when he got bitten. Now Rodney went back to spearfishing and working with us. Never had a problem at all. He understood like Ron and I did that sharks don’t swim around saying, oh there’s a human, I’m going to bite them or eat them. It’s usually an experiment on behalf of the shark or an accident.

Although I’ve been bitten several times, only one was bad. When Ron invented that suit, I realized how hard it was to get a shark to bite me. They were hesitant. Only one out of twenty would swim in and take my arm. But that was enough to test this theory, which worked. To this day, it works. It wasn’t a new idea, it was a new adaption of an old idea. Mesh was used as armor a long time ago and it worked very well until they invented the crossbow. Swords and spears didn’t go through it, but the crossbow went straight through a man out there in chain mail. Shark teeth will never go through. They don’t have the pressure in their bite. And I know, I’ve been bitten many, many times. Scientists would have us believe otherwise, but they’re wrong. It’s very hard for an uneducated person like myself. I left school when I turned fifteen. I think right now, they’re starting to understand. They’re realizing that sharks aren’t just big fish looking for humans to bite, there’s a lot more to them. They all have personalities. There’s the nice guy, the cranky guy, the dangerous guy. Not just sharks, all fish. It’s an amazing world, and I’ve had a wonderful life.

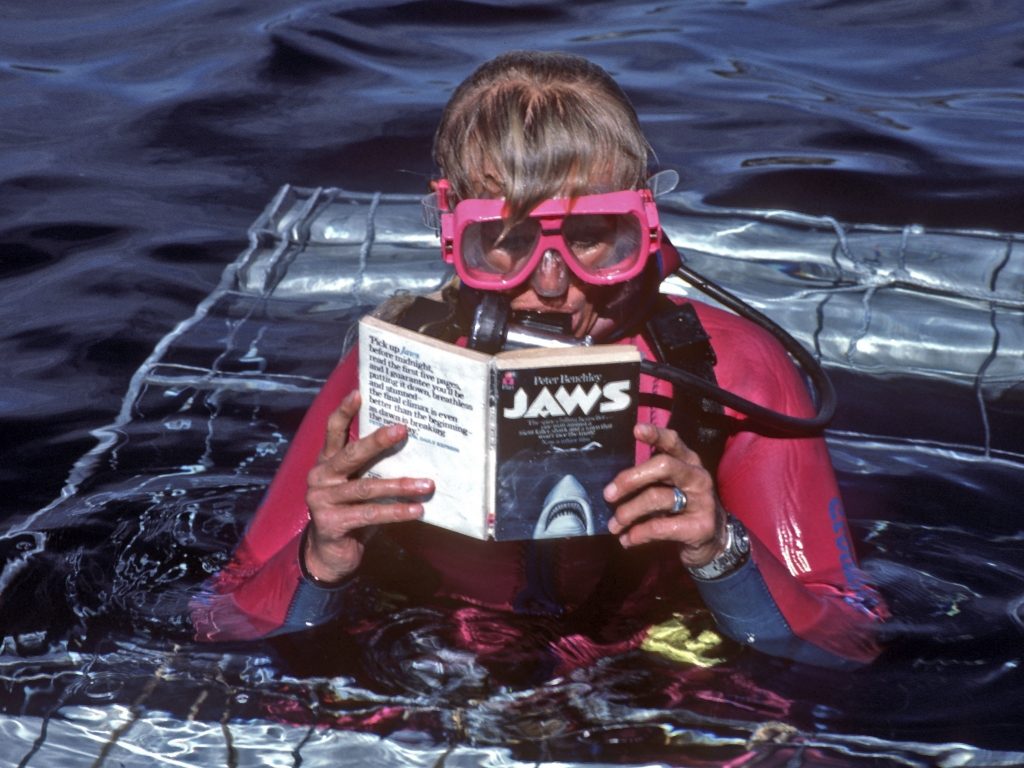

(Q) : What was the first impression you had when Universal sent you Peter Benchley’s book Jaws, and how did you decide to embark on this project?

Valerie Taylor : Well, Richard Zanuck and David Brown, the producers of Jaws, sent us the galley proofs of a book written by an author called Peter Benchley. They asked us if we thought it would make a good movie. We both read the book, and we thought there would be a lot of work, and so we wrote back and said, yeah, of course. They were very smart. Steven Spielberg wanted to get all the live shot footage before they went into production. They realized this was a very important aspect. It’s no good shooting a scene that is a fake that looks good if you can’t improve it in the end result. Our work was the cream on the pie. It was interesting. We had a good time and enjoyed it all. Ron had an experience underwater where the cage was broken off the side of a half-size boat.

Everything was half-size for filming. And pulled a half size cage down into the ocean, twirling around, fighting to get away. And Ron filmed it. It wasn’t in the script, but they put it in the script. It was a good piece of action that they could not resist. None of us expected Jaws to have the impact on the general public that it did. We were very surprised and extremely distressed. And we went around America, Universal had us do every talk show in the United States telling the people not to be afraid to go in the beach. That it was a fictitious shark in a fictitious story. And there were no sharks really like that in the ocean.

Not that big and not that ferocious. It was very successful and led to many more shark movies. The scientific world really picked up their action on researching all different species of sharks, which they do to this day. Unfortunately, as you probably know, sharks are being slaughtered for their fins at an accelerating rate. And eventually we’ll wipe them out, and in doing so, we’ll wipe out possibly even our own lives. Nature has life on land and life in the ocean, and it works perfectly. We’re changing it.

(Q) : How do you manage to put all that material together in a seamless way for the audience to see the content? It’s not just Valerie in the past but also what’s going on currently in the world to send a message to understand what needs to be done after the pandemic when people can get closer to nature. What was the message you wanted to convey in this film?

Sally Aitken: First of all, yes, it did not happen overnight. It was a big job. Look, there’s a lot in that question. To go to the very end of your question first, in terms of what was the message to convey? One of the things that we worked very hard in the film to try and achieve was the space in the film for people to draw their own conclusions, to have experienced the marine world in part through Valerie’s own experiences and to go on their own journey of maybe perception change around sharks and the awareness that they aren’t these marauding fish that they might have believed in starting the movie.

But also, you spoke about interconnectedness, and I think that was something that became more and more apparent, actually, the more we’ve had reaction to the film, it wasn’t such a conscious thing, but I do think there’s a strong appetite there for it, and I think partly Covid and the pandemic has in some ways brought us closer to the desire to live harmoniously with nature. So, in terms of making the film, we started with a huge volume of material, as you will have seen, the footage, the photographs and the slide film. We looked very carefully at which aspects of Valerie’s life could lead us into some of these understandings, so, for example, the experience that was a defining moment in making Blue Water, White Death, one of the world’s first ocean action nonfiction features, wasn’t only an exciting adventure at the time, which it was.

It wasn’t only an example to the rest of the world of how charismatic sharks are, which it was. And it wasn’t only an example of how humans can in fact make a place for themselves in the pack and be at one with other marine creatures, which it was. It’s also today a historic record. And so, all of these things, because those sharks, you just don’t find those sharks in the Indian Ocean anymore. And so that wasn’t present then, but it is now. So all of these things played a role in how we were constructing the film and how we chose to put both the archival experience but also today’s knowledge in the same moment. It was a great, great testament to the skill of our friend and editor Adrian Rostirolla, who has such a beautiful way of compiling archive alongside testimony. We just kept going back to the archives and encouraging a cinematic approach to the use of that archive and complement to the footage that we filmed along the coast and with Valerie at a very special spot in New South Wales called Seal Rock. So it was a huge adventure, in a way, making the movie, and a huge undertaking. But in the end, we were actually striving for an emotional, heroic, adventurous experience through which an audience might be able to reflect on their own life and that of the planet that they share with other creatures.

Here’s the trailer of the film.

“Playing with Sharks” will debut on July 23, 2021 on Disney Plus.