Synopsis : Filmmaker and photographer Elizabeth Lennard secures unprecedented access to Ryuichi Sakamoto during the recording of his 1984 album Ongaku Zukan in this brief-yet-insightful Franco-Japanese television co-production. A sampling of studio sessions and performances (including a piano duet with then-wife Akiko Yano), archival footage and talking head interviews, Tokyo Melody finds the eccentric artist at his creative peak, pushing the envelope to new sonic frontiers as he reflects on modern life, shifting technologies and his own creative processes. Lennard captures an awe-inspiring portrait of the extraordinary musician—one that taps into the very nature of the artist’s raison d’être and remains a testament to Sakamoto’s profound brilliance.

Dir. Elizabeth Lennard, 1985, 62 min., 16mm, color; in Japanese, English and French with English subtitles. With Ryuichi Sakamoto, Akiko Yano.

Exclusive Interview with Director Elizabeth Lennard

Q: This film was originally from France. What’s your relationship to Ryuichi Sakamoto and how did you get such unprecedented access to film Sakamoto during the recording of his album, “Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia?”

Elizabeth Lennard: He had just made “Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence.” So we’re talking 1984 or 83, I think it was 83. At the time, he had already been in the band Yellow Magic Orchestra. I don’t know how much the Yellow Magic Orchestra is remembered in Japan. They had done a US tour in the’70s, but I don’t think he was so well known here unless [they] were very specific Japanese music fans. I don’t think he was known in France. Obviously he was on the US tour in the ’70s so there were people who knew him in the US from Yellow Magic Orchestra, but again, this was at the beginning of his solo career and in France, he really wasn’t known.

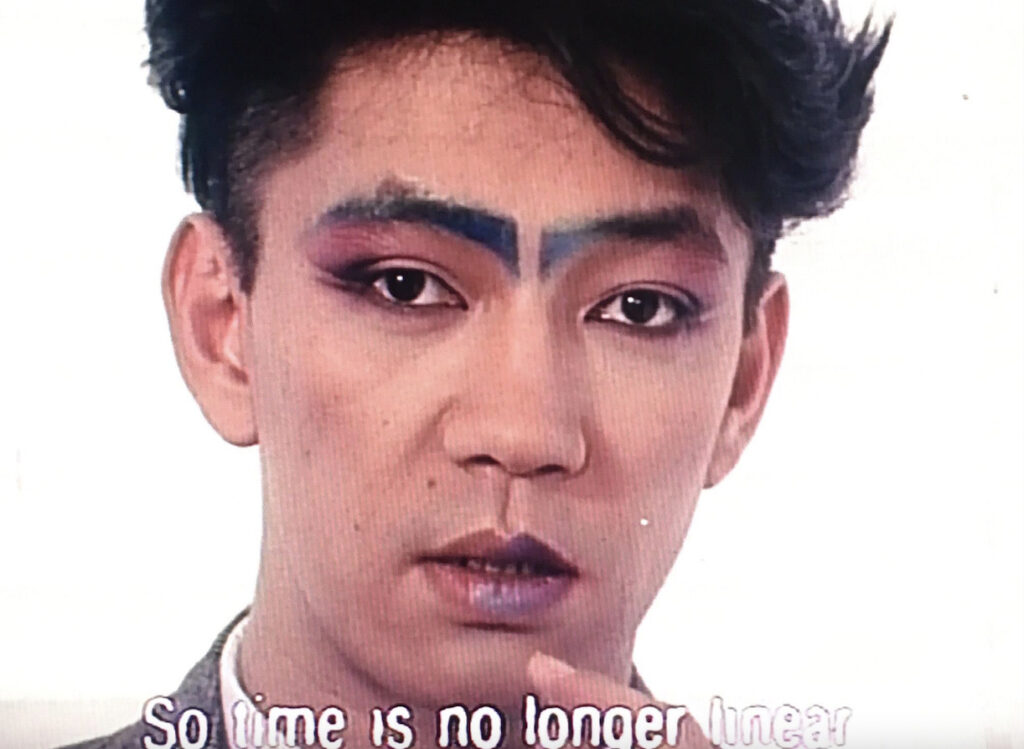

It was his first film music as far as I know. I don’t know everything for sure, but it was obvious this was the first international film music that he had done and it was a big step for him. I saw the film at the Cannes Film Festival and was completely blown over by the music by him — by everything. I was very lucky because at Cannes, there were two producers; I knew a little bit from French experimental TV. They saw his makeup, and thought he and the music was incredible. They said, “If you could find a way to contact him, maybe we could find some budget for you to make a film about him.” I was very young, but I had already started making films and made one in 1984 about two French musicians called the Labèque Sisters [“Duo with Katia & Marielle Labèque,” 16mm, 26 min. also produced by E. Lennard]. So they knew I wanted to make films, but nobody knew how to reach him and we are talking pre-fax days even. People still had faxes but no free internet. So, the next challenge was to find a way to get in touch with him.

Q: Luckily he was not that reclusive. That’s why you were able to find him, but it must have been a hassle in those days to reach him. In the beginning of the film, he talks about this concept of changing, and creating a new music. In 1985, he was talking about it like he memorized the idea and a concept that you could apply individually to different parts. It’s not a linear music concept that he was coming up with. He applied with the time that is probably appropriate when people consume music in different locations. When you walk by, you hear certain pieces of music or a certain part of it. He was completely aware about how people were consuming music at the time. It was really surprising how he conceptualized the music.

Elizabeth Lennard: Let me explain. At the time, Marshall McLuhan, who was actually Canadian, had a big influence in the ’50s or ’60s and was talking about time and our relationship to time. There is a whole movement of McLuhanism and it was something I knew about because my father was a sociologist. McLuhan’s books were in the house and so forth. I’m not going to go into McLuhan, but the specific thing about his notion of the nonlinear is where Marshall McLuhan comes in. It’s all about the nonlinear aspect of time and the way Ryuichi applied that to music — that became something as you noticed.

Today, people listen to music in a different way than they were listening to it then. We’re talking about 1983, or ’84. It’s something that my film also shows in the sense that there is a beginning and end and a middle and it’s kind of a nonlinear concept even in the film. I think at the time, it was already better understood in Asia or in Japan than in the US. That was my feeling and I definitely had that in common with him when he was talking about that. It seemed, for the rest of his career, something that he thought a lot about in terms of his compositions and recordings.

He did a whole thing about how the beginning, middle and end is a very good point because when you make documentaries, particularly in the United States, they want to teach you to have an arc. The beginning, middle and the ending for the arc and so forth. It’s really the way they teach you how to write a script. I went to UCLA film school in 1974 and left because not only was I the only woman in my class, but they wanted you to write a Hollywood screenplay in that way. It wasn’t really what I was interested in and, in being able to meet Sakamoto and make this film about him I found he had a similar idea — even of filmmaking.

Q: What was the process of shooting him? There’s a sequence where he’s taking a picture of the scenery or something like that to get some kind of inspiration. What approach did he do during this shoot that surprised you?

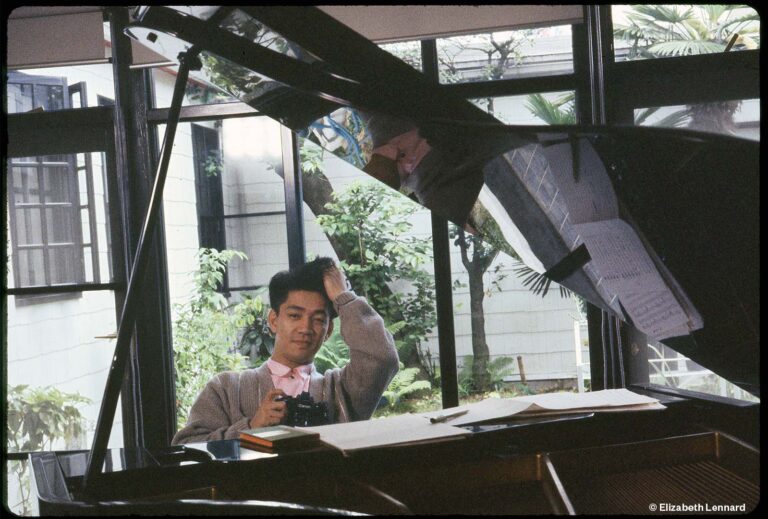

Elizabeth Lennard: This scene with the camera, I don’t know if you can see it, but it’s a fake camera. It’s a toy camera. I bought that in Tokyo because I knew that he liked to take photographs. It was something I found in Tokyo and for me, it was unique because it was a camera that also made a sound like it turned into a little toy gun.

I think that amused him, also we went to Meiji Park, which is quite central in Tokyo, as I remember. You can’t make equations but in New York you have Central Park from what I remember and, again, correct me if I’m wrong, but Meiji Park was a very central park — like a public space. It’s a very beautiful park, like Central Park is. And we were, it was improvised. Everything was somewhat improvised with him. I brought him there and gave him the camera and it was improvised.

Q: He was really getting inspiration from [the sounds around him] because, later in his life, he was carrying around a recorder to capture, or find new sounds. What was his process of getting inspiration when he was in the ’80s. Did you notice how he was getting his inspiration?

Elizabeth Lennard: I didn’t follow his whole career. I did learn that he had gone to Fukushima and that he was recording sounds. I don’t know where it was, but it was in the snow, we were on the same wavelength about this film. Again, the idea was a portrait of Sakamoto and a portrait of the sounds of Tokyo. He was very into it and I was very into it. For me, that’s what I was looking for when I was filming things. I filmed the pachinko machines right there and you can hear the sound of the ticket takers in the subway, which I don’t think they have anymore. Obviously it must be computerized now. I don’t know, I haven’t been back.

Q: In the United States basically you put cash on the card, and you can do that while staying at home and all that. So it’s pretty much the same.

Elizabeth Lennard: But punching the tickets at the subway, for me with a foreigner’s ear, it was, in fact, the ticket punching sound. I don’t think they had that in New York. It was the token.

Q: It was a token. In New York it was always putting a coin in there.

Elizabeth Lennard: I’ve been in France for a long time. There might have been ticket punchers at one point. But I didn’t know, I don’t know when they had those. But anyway, I liked the ticket punchers and then going to people praying and the sounds or sweeping, all of those sounds were lovely sounds that I enjoy. So, and then at the same time filming Ryuichi in the studio with his Fairlight, which was this new, you know, brand new machine.

It was his new baby that was very expensive at the time that now people can do that kind of, you know, sound sampling in their phones probably. But he was very into, early on at the time, what you call sound sampling. I don’t exactly know. Is that what it’s called?

Q: It’s sound sampling. In those times, they used that term but now everything is computer music and he was keenly aware about how mainstream culture had lost its authority. In the ’80s, it started to change — the dynamic shift was there. He mentioned the technology of a computer that his generation was developing. He was keenly aware of what was going on around him. Do you ever notice, while you were filming, his awareness about the future, caring about the situation and all those things of society that were changing?

Elizabeth Lennard: I grew up in New York City and California and then lived a lot in Paris. But when you go to Japan, you learn that New York seems like a small town after Tokyo. It seems old and small. New Yorkers think New York is a big city and that’s all there is. in New York. But when you get to Asia, when you get to Tokyo and I haven’t been to China. But even at the time in the early 80s, it’s kind of a shock in the kind of, you know, how much the world, world culture, how much Japan had in itself was already in some way, absorbing world culture and and Sakamoto even more, you know, he was a very cultured person.

So he knew, you know, Debussy, he knew classical European music, but he also knew Japanese music. It’s a bigger scope. And it’s very strange for New Yorkers because they think it’s the center of the world, I hate to say, do you know what I’m [talking about]? I don’t know if you agree. Because of global culture now. But I’m talking about the ‘80s when things were not so global. So, he was very aware of world culture.

Q: In a film, he was talking about how he composed the music for “Merry Christmas. Mr Lawrence.” He borrowed dramatic structures and relationships between the characters and melody. It became his motif in a way and then he ordered all orchestration, decided on the scoring. He was focusing on two of the characters. We rarely hear him talk about the concept of how he creates the music in any of the interviews. He rarely granted interviews about film-making. How were you able to get that out of him? How did you get him to talk about his concept of composing the music for the film “Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence?”

Elizabeth Lennard: I was very naive then. This was the first film I think he did just for France. It’s very hard anyway for a composer to put into words how they compose music or do any artistic process. It’s hard to explain. You can’t. Of course, he went on to do many, many scores. But at the time I might have been the first person to ask him that question. Or, at least, I was the first person from Europe to ask that question. It was very spontaneous asking him about that — I didn’t think about it before and he knew the film was a portrait of him. Since then, I’ve made other films and worked with composers and how a composer composes it.

It’s very hard for them to explain and then, movie music, movie scores, that’s a specific thing. It’s something that’s in the background of a film. It’s a very hard question for any composer to answer. He definitely explains what the music is, where it comes from or what it meant to him. Between the characters, he’s also a great artist. No matter what, it doesn’t explain where the challenge comes from. You can say, I want to do this and this and this character and the music will represent this character and this theme. But that doesn’t tell you actually how to compose the music. You know what I mean?

Q: In his conversation about David Bowie, he [spoke about] how he dealt with media scrutiny and that it might be the factor or reason there’s a certain limitation or fear of stagnation in Japan in those days. That might be the factor of media scrutiny that he hated that led him to move to New York. Intrigued by the conversation about David Bowie, it’s interesting that he not only respects him as an artist and musician, but also he respected him as an actor as well. He had such a charismatic presence just as Sakamoto did. Is there more footage or was the only time you will be able to film that? It’s intriguing to see him talking about David Bowie.

Elizabeth Lennard: What was in the outtakes? It was almost 40 years ago. I can’t remember. It’s interesting that he was a huge star in Japan at the time but David Bowie was a world famous person and it’s true, how he says he learned from David Bowie how to be himself in the media. It’s not a problem that I ever had. It’s something that, obviously, he figured out how to deal with. Again, when I made the film in Tokyo, he was already very well known. He was always in his limousine or in the studio.

He was very protective and, maybe, that’s one of the reasons why, at some point, he decided to move to New York possibly because he wasn’t as recognizable there. David Bowie moved to New York, John Lennon moved to New York, so there’s some kind of anonymity in New York, which is known. It has that reputation for people. It’s not that people don’t recognize each other but since everyone’s so busy, they don’t necessarily pay too much attention to you. It was something that’s part of the reputation. it’s really a problem that major stars have; he obviously recognized David. He says that he saw how David Bowie acted in the media. Maybe that helped him to be more relaxed about it.

Q: The scene between Sakamoto and wife Akiko Yano [she was a pop star herself] playing the piano together was surprising. It’s really valuable footage that they are playing together. What were they like, when they were together. How was it like seeing them together?

Elizabeth Lennard: That scene was really improvised. We asked if we could film Sakamoto at home playing the piano at home. He said, “Well, I don’t know. I have to ask Akiko.” In Japan, at least at the time the woman was the one who decided what’s going to happen in the home, you know, I don’t know if that’s still the case.

Q: In the ‘80s, there was still a very male, chauvinistic perspective. The man usually controlled the household. In Sakamoto’s house, it was totally different and more like an American way —that the woman would take care of the woman first.

Elizabeth Lennard: I was under the [impression] that maybe it was kind of chauvinistic in Japan, but that in the home, the woman was the boss. That’s what I understood.

Q: When a man has a successful career, they never control the household because they’re busy with their own creations. It’s particularly the man who has the generosity and talent so that they let the woman take control in the household. It’s fascinating about their different shifts in perspective when they control their own creativity in a different setting.

Elizabeth Lennard: We did go there spontaneously; it wasn’t planned. Akiko agreed to play the duet with Ryuichi And honestly, I only found out recently that it was on youtube. Apparently, that was the only time they were filmed together at home. Ryuichi Sakamoto, from what I understand, was really a composer. He was obviously known as a performer but also as a composer, whereas Akiko Yano, from what he told me, was even more of a performer in terms of being a musician, like a pianist. You can see that when they’re playing she’s the pianist and it is true that it’s a lovely duet they do. She has a band aid on her finger. Nobody asked her to take it off and that band aid will be there forever. They did seem very happy when they were playing the duet. Again, I was only told recently that it was maybe one of the only times they were filmed together playing the piano at home.

Q: It’s really rare footage. They are never seen together talking or playing with each other.

Elizabeth Lennard: It was an NHK documentary on July 6th where they did use a tiny bit of the footage from “Tokyo Melody,” but I haven’t seen it. I don’t know how I can see it.

Q: This was shot and then came out in 1985. You must have been shooting in ’84 or something. I’m curious if he had any concept for “The Last Emperor” soundtrack because that movie came out a couple of years later.

Elizabeth Lennard: I don’t think so. We filmed in ’84 and edited all summer and several months after. We filmed in May ’84 and then edited. I noticed just now it was actually only broadcast in France in ’86. I thought it might have been broadcast in ’85 but it started on the festival circuit in ’85. Once I finished the film, Ryuichi Sakamoto came to Paris to see it — he must have been in Europe on tour or something — but I don’t know what he was doing. And The Last Emperor,” I don’t know. What year was “The Last Emperor?”

Q: It’s 1987 or something.

Elizabeth Lennard: It’s three years later when he was contacted [by its producers.] You have to figure it out because I’m sure “The Last Emperor took quite a bit of time to make. He plays [Amakasu] in “The Last Emperor” and obviously he’s in makeup and costume but he does look older.

Q: It’s a totally different look from when he was in “Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence.” Then he did “The Last Emperor.” What do you want an audience to take away from this wonderful documentary?

Elizabeth Lennard: I’m very happy that people can see the documentary because we were all younger then. I do think that he was true to himself in the documentary and he continued to be himself throughout his life. It comes back to what David Bowie said to him — to be yourself. And because of Yellow Magic, maybe he didn’t feel completely that he was faithful to himself? I think being faithful to what you want to be is important and to be able to live your life and do that for your whole life is rare. A lot of people don’t get to do that.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.