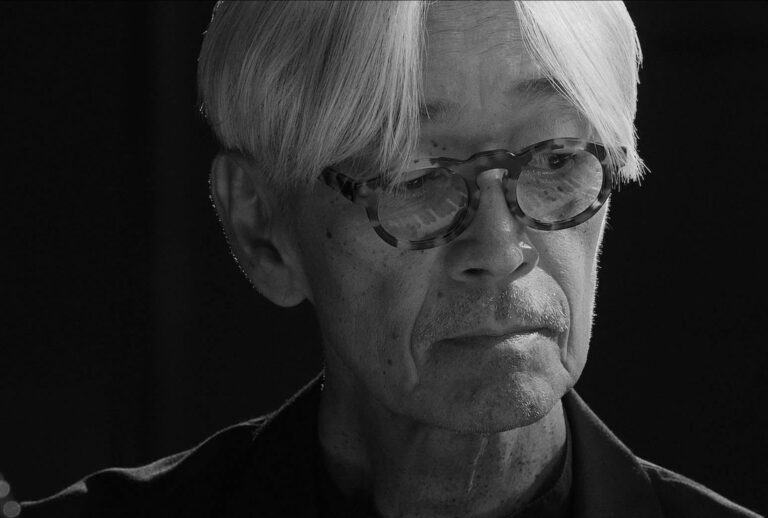

Synopsis : When Ryuichi Sakamoto died in March 2023 at age 71, the world lost one of its greatest musicians: a classical orchestral composer, a techno-pop artist, and a piano soloist who elevated every genre he worked in and inspired and influenced music-lovers across the globe. As a final gift to his legions of fans, filmmaker Neo Sora (Sakamoto’s son) has constructed a gorgeous elegy starring Sakamoto himself in one of his final performances. Recorded in late 2022 at NHK Studio in Tokyo, this filmed concert is an intimate, melancholy, and achingly beautiful one-man show, featuring just Sakamoto and a Yamaha grand, as the composer glides through a playlist of his most haunting, delicate melodies (including “Lack of Love, “The Wuthering Heights,” “Aqua,” “Opus,” and many more). Shot in pristine black-and-white by Bill Kirstein and edited by Takuya Kawakami, this stirring film brings us so close to a living, breathing artist that it feels like pure grace. A Janus Films release.

Genre: Documentary, Music, Biography

Original Language: Japanese

Director: Neo Sora

Producer: Norika Sky-Sora, Albert Tholen, Eric Nyari, Aiko Masubichi, Jeremy Thomas

Runtime:

Production Co: Bitters End, KAB America

Q&A with Director Neo Sora

Q: Say a little bit about making the film and the origin of the project?

Neo Sora: The film really started with him [Ryuichi Sakamoto]. He really wanted to do one final concert but was too physically ill so he was unable to do a live one. He had to sit in front of a piano for an hour and a half or two hours straight so we decided to do a film where we can split up the performance over the course of multiple days and string it together as a concert film which makes it feel like a continuous concert.

Q: He came up with the set list?

Neo Sora: That’s right.

Dennis: Did you talk about that?

Neo Sora: He came up with the set list. He usually comes up with a set list pretty close to whatever the performance he was doing but this time, it was a film and films take a lot of preparation,I said, “You’ve got to make the set list early so we can prepare, plan the shots and everything.” He was like, “I’ve never done that before,” and I was like “You have to do it this time.” He prepared the music but I suggested the overarching visual theme of the film which was the passage of time over the course of a day. We were thinking about planning the lighting to mimic a kind of night at first and then gradually it becomes morning then midday and back to evening and night again. Once I suggested that, he rearranged the track list a bit to fit that arc so he would take one song and be like, “Oh, this one feels a bit more like morning so maybe we can put it here and this one feels like afternoon.”

Q: How many days was the shoot?

Neo Sora: Eight days. He played about maybe three to five songs per day, and we only had about three takes per song so it was a pretty nerve-wracking shoot.

Dennis: Talk about your collaboration with your cinematographer Bill Kirstein who is here as well. You sort of mapped out each song in the visual language of each track.

Neo Sora: I feel like I did very little because Bill is such a magician with the camera and lighting. I had to lean on him for the most part but we listened to the music a lot and internalized the music in our bodies and muscles. We had two other really fantastic camera operators, Motomu Ishigaki and Kaori Oda, who’s also a filmmaker. We had a general plan for the cameras to capture certain things at certain moments in the songs. But in between points A and B, which we defined, we just left it up to the camera operators including Bill to be as reactive to the music and let them find whatever they wanted to see at the time. So much of the film was about picking up on the little gestures or expressions so there was a lot of a kind of an improv within a freedom within a structure.

Q: It is really moving that you left in some sort of imperfections and the sort of start/stop moments. Talk a bit about that?

Neo Sora: There’s one song, “Bono Alora,” in which there’s an improvisational section in it. The one in the film was Take Two — in that take, he pauses the improvisation and considers the harmony. He’s playing something about it but it’s not right. It’s, I don’t know, like a path in the woods that doesn’t exist that he’s searching for and plays it over again to try to explore different harmonies within that. It’s a very dissonant moment within the song and there’s something that really was… I don’t know. Watching it was extremely intriguing because I don’t know if I’ve really seen a musician on screen searching for the right sounds live. Of course, we filmed the take. After that was a perfectly good take, but we kept the imperfect one in because there was something a little bit more — I don’t know — mysterious about this one. In the studio it was just such an intimate performance.

Q: How many people were there in the studio?

Neo Sora: There were a good amount of people. This was actually like a concert for us. In fact, I was actually outside, in the booth. We filmed at this place called 9 Studios in NHK which had a bunch of rules and they didn’t allow us to use any wireless systems at all because it would interfere with the radio signals that they had — stuff like that. So everything connected was wired so there’s like hundreds of feet of cable all around the floors as far as you could see. We needed some cable wranglers and they had to be silent. All the floorboards were wooden and they kept creaking so we had to put down blankets and weights and stuff like that. So there was a lot of hands-on-deck to try to keep as quiet as possible. Everyone was wearing socks I guess.

Q: This is an intensely emotional film. It’s the beauty of the music and the performance but also the knowledge that it was his last performance. What was it like to be there while you’re also making a film? People know that you’re Sakamoto’s son so obviously there’s a close connection with your subject. What did it feel like to be making this at the moment?

Neo Sora: A lot of people have asked me this question. I’m going to tell you a maybe not-so-touching answer which is that it really felt there were a lot of practicalities that go into making a film — making sure it’s captured correctly so, to be honest, I was really focused on that. But I think that our relationship really allowed us to push him a little bit more. For example, I don’t think he would have conceded to make the set list so early if hadn’t been his son. I asked him for it so I think that led us to really focus on the filmmaking.

It was really tense and you could really feel that he was straining himself. That’s not to say that we didn’t think about his mortality and possible death — [to say otherwise] would be a lie. But, that being said, once he sat in front of the piano, he was extremely energetic and alive. It was exhilarating to see that. Usually, whenever he was really conscious of the camera — whenever you point the lens at him — he made a cool face or acted a little silly but something happened when he started playing, he started making these really weird faces.

He really got into the music and made incredible faces as he was listening to his own music that he’s playing. He’s feeling it. It’s like there are times when he looks like he’s threading a needle or just feeling the chord or just feeling something delicious and he has that really pained expression or something like that. And it’s just really fun to see that. I was watching that in the booth and was like, “Yeah this shot and then we cut to this shot and it was there.” It was a lot of fun for me.

Q: Did he see any of the footage?

Neo Sora: Yeah, he saw the completed film.

Q: Talk about Sakamoto’s relationship with Cinema and how it was passed on to you. You’re a filmmaker; you had a short film [that came out] a few years ago and you just finished shooting your first feature. Can you talk about that?

Neo Sora: He obviously was a musician who did many different things but Cinema was so important[to him]. I think he was one of the composers who truly understood Cinema. It was also, of course, a great screen presence. I think his first memory of listening to music was in the movie theater. I’m pretty sure it was “La Strada” by Fellini. I didn’t know how old he was [then] but at three or something [like that] he was on the lap of his mother watching the movie.

He talked about how he could still remember the melody of the music, I think Cinema was always with him. Obviously, one of his most famous pieces was “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” which was his first film score. It’s incredible. I watched the movie recently for the first time actually. I mean not that recently; I don’t know, 10 years ago or something like that. I watched it after studying film and starting to make films myself. It’s such a strange soundtrack, really odd and it completely steals the scene.

A lot of film score [composers] say you shouldn’t do that but it’s really iconic and memorable. I feel like the music also evokes the film. What some of the best film music does is give you the image immediately. He really appreciated films that told or gave you communicated emotions and communicated ideas in a nonverbal way. He brought that to his music and music is one of the media that can deliver emotion in one of the purest ways possible. We tried to do that with this movie too. We didn’t want to burden it with a narrative or words because the music did all the talking. I like that in films [as well] and it feels like that’s something I definitely inherited from him.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.