@Courtesy of Neon

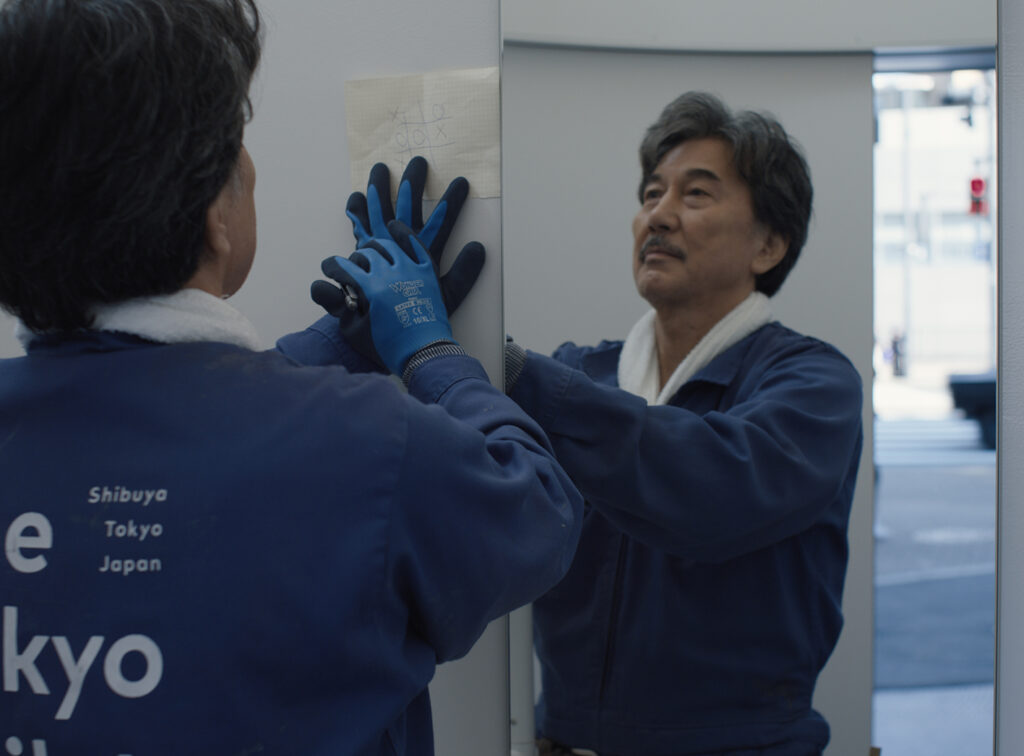

Synopsis : Hirayama seems utterly content with his simple life as a cleaner of toilets in Tokyo. Outside of his very structured everyday routine he enjoys his passion for music and for books. And he loves trees and takes photos of them. A series of unexpected encounters gradually reveal more of his past. A deeply moving and poetic reflection on finding beauty in the everyday world around us.

Rating: PG (Some Language|Smoking|Partial Nudity)

Genre: Drama

Original Language: Japanese

Director: Wim Wenders

Producer: Koji Yanai, Wim Wenders, Takuma Takasaki, Yusuke Kobayashi, Reiko kunieda, Keiko Tominaga

Writer: Takuma Takasaki, Wim Wenders

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Runtime:

Distributor: NEON

Production Co: Master Mind Productions, Inc.

@Courtesy of Neon

Exclusive Interview with Actor Koji Yakusho and Co-Writer/Director/Producer Wim Wenders

Q: Let’s talk about the creation of the character Hirayama with screenwriter Takuma Takasaki. In creating the character, you took some inspiration from the singer Leonard Cohen [who left music for several years to study Buddhism in a monastery]. Hirayama gave his love and compassion to his friends and family. That’s the essence of a human being. It doesn’t matter how much money you have or how famous you become.

Wim Wenders: Though the character Hirayama isn’t living in a monastery, [rather], he’s living in the middle of the city in a little place [that’s very austere]. There’s something monk-like about his approach to life in the way that he reduces his possessions and he looks at each and every person as if they were the same. He looks at the homeless in the same way as he looks at the banker who comes into the toilet. For him, people are alike; [he loves them as he does] the light and trees as well.

For me, [the late singer/songwriter] Leonard Cohen was a great inspiration. I met him when he came back from the [Buddhist] monastery where he stayed for 10 years. That was a good model for the character. I knew other people who actually did public work or worked as servicemen with great dignity. Some of them I met in Havana, for instance, and they did public work with great dignity. There are several characters that contributed to [who was] Hirayama There was also a little bit of that in my Guardian Angel [who wasplayed] by Bruno Ganz in “Wings of Desire.”

Q: Mr. Yakusho, you play a role that has very few lines during the film, how did you and Director Wim Wenders work together to fill out the gaps between the lines before?

Koji Yakusho: It’s clear that there weren’t many lines, particularly in the first part of the story. The character Hirayama-San expresses gratitude for the time he spends in the bath, reading a book, or having a drink, as well as in his own work. Despite the lack of dialogue, he concentrates on his effort [in an expressive way].

The only time he takes a break from his work is when he sees the sun shining through the trees and feels something very peaceful, which was described in the script. In that sense, I thought that even if I didn’t have any lines, I could use my acting [in making] this movement to express this time as something to cherish and focus on. The director followed the cleaning process without rehearsing it, which made me think that if I could do it in the same way that Hirayama does it, it would convey a message to the audience.

Q: This film doesn’t rely on any dialogue much like the work of Aki Kaurismäki, Theo Angelopoulos or maybe even Andrei Tarkovsky. What could be very mundane could also be very beautiful when you pay more attention to people and observe them closely. Talk about how you crafted the script without much dialogue?

Wim Wenders: If a character doesn’t have many lines of dialogue, something else becomes even more important — it’s the way he looks at the world. In the place of dialogue in our script, there’s descriptions of what he sees. If you have a film with such a central character as Hirayama where he’s in every scene of the film, then slowly, the viewer adopts his point of view.

The way he looks at the world becomes the essence of the film. Even more important, because he doesn’t speak, his eyes are a much more important, expressive tool of his. All of a sudden, it gets much more important in what he sees and how he sees it. It [defines] how he looks at the world. The film is very much about his viewpoint. The fact that he sees it in his eyes also [helps him] to live in the here and now. That is, I think, a great feat that Koji Yakusho managed to achieve in the film — to really become talkative through his eyes.

Q: Mr. Yakusho, when director Wim Wenders explained the background of the character Hirayama, what was your primary way of preparing for this role?

Koji Yakusho: Although the script didn’t give me all the details, it gave me a sense of what it was going to be like. As for what may have happened in Hirayama’s past life, in any other script, If it is not written, then I think it’s the job of the actors to weave their own story about the background of their characters.

Initially, I had created my own narrative and played Hirayama with my own style, but during the filming, the director gave me a memo about Hirayama’s life to date. The note was a powerful one for me to craft Hirayama’s character, particularly because it highlighted the connection between who he was and the sun emerging through the trees, which was a very powerful idea for the latter half of the filming.

@Courtesy of Neon

Q: This film doesn’t show much of Hirayama’s background, except his relationship with his sister and niece. In order to comprehend the character of Hirayama, what conversations did you have about Hirayama’s background with Koji Yakusho in order for his character to come across to the audience?

Wim Wenders: In real life, you sometimes meet people under intense conditions. You know them for a long time, like in work situations or in friendships, but you don’t know their biography. I felt that, in this film, it was a beautiful idea that we didn’t know much about how Hirayama became the man he is now. We guess a little bit that he must have had a different background, but I very much liked the idea that the audience had to fill it in — everybody has to create their own version of Hirayama’s story. This is what we do in life. Not many people tell us their life story.

As the director, of course, I had to know it. I did write it down and when Koji asked me about it, I felt that he was the only person I had to show it to. I didn’t want it to be in the film or be explained, but he should know my idea of his backstory, how he became the man he is now, what led him to be so content with the life he’s living and what provoked the choice to live the life that he’s living now. He was not born as a toilet cleaner. I gave him my story and he read it. I think both our ideas were very much overlapping and he especially liked my connection between Hirayama and the sunlight, of the play of sunlight on a wall which is known as Komorebi in Japanese. In my biography of his life, this played an important part and I think Koji used it to the maximum.

Q: Mr. Yakusho, could you provide us with your research on Hirayama’s job as a janitor cleaning toilets? Have you spoken with actual janitors? What impressed you during your discussions?

Koji Yakusho: I was instructed for about two days by a member of the cleaning staff of the Tokyo Toilet Project, and he was present during the entire shoot. We interviewed various cases, asking questions about movements depending on the director’s direction, what to do when a guest comes in while cleaning, keeping a good distance from people using the restrooms, and how dirty the restrooms sometimes are and so on.

Even if you clean the toilet three times a day, it still gets dirty. However, the Tokyo Toilet Project encourages people to use toilets cleanly without putting up a sign saying so. I also interviewed them about various cases, such as how dirty the toilets can be.

Q: What’s really engaging about this film is that it shows the life of a guy who may just clean out toilets but it was the way Hirayama approached his job, making his equipment, so that he carefully cleaned out a toilet. There’s a certain nobility to the way he worked. Talk about why you chose that as his vocation.

Wim Wenders: I can add a little thing to it. I liked the idea and saw in these people who did the real job, they looked at it as a craft and actually produced instruments that allowed them to do certain aspects of the job like looking under the urinal. It’s difficult unless you have a tiny little mirror that you can push underneath it. So I liked the idea that Hirayama was looking at this job, not just as a service job, but as a craft. Craft people have an incredible dignity, self-respect and a dedication to work that’s different from service work. I tried to make Hirayama more of a craftsperson.

Q: The choice of songs you used seemed quite important to the film: Patti Smith’s song “Redondo Beach;” “Pale Blue Eyes” from the Velvet Underground; Lou Reed’s song “Perfect Day” and Nina Simone’s version of “I Put A Spell on You.” Talk about working with these musical choices for the soundtrack. How did you select the music?

Wim Wenders: Because there isn’t so much dialogue in the script, music became much more important. It helped tell the story, explaining where he was, where he came from, and what his background was. Sometimes the songs really in a very subtle way help tell the story.

When Takuma Takasaki and I started to write the script, we loved the idea of cassettes, [like the type] that you would have when you drove an old crummy car. So when we wrote the first routine day — when he goes to work — I said, “We should put on what he’s listening [to] because that will help us understand who he is.”

Takuma said, “You choose,” and I said, “I hear him listening to ‘The House of the Rising Sun.’” Immediately, I got a second thought and said, “But I can’t impose my taste on this Japanese character. Maybe he would listen to something altogether different.” Then Takuma said, “Oh, don’t you worry. You can be sure that in Japan, we listened to ‘70s and ‘80s music that was exactly the same stuff that you listen to like the Rolling Stones, The Kinks and the Velvet Underground.

Then I remembered that actually, one of the two times in my life I saw The Kinks, they were in Tokyo and that was one of the best concerts I ever [attended]. I realized, in terms of music, it’s a universal language and it would be good [to include such songs] because they would help audiences all over the world be more in touch with Hirayama if they recognized his musical taste.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.