“Little Richard: I Am Everything” is a documentary about the life and career of the late legendary Rhythm & Blues singer. Born Richard Wayne Penniman, he was a queer black man from Macon, Georgia, whose flamboyant lifestyle and energetic showmanship burst onto the rock and roll scene.

Even though he had difficulty with his father, Richard established himself through the chitlin circuit, drag shows, and dirty blues performances. He broke boundaries and normalized “outrageous” behavior, and followed in the footsteps of such openly gay Black artists Billy Wright, Esquerita, and the gospel singers Ward Singers and Marion Williams — who all offered the roots for the style of this colorful artist.

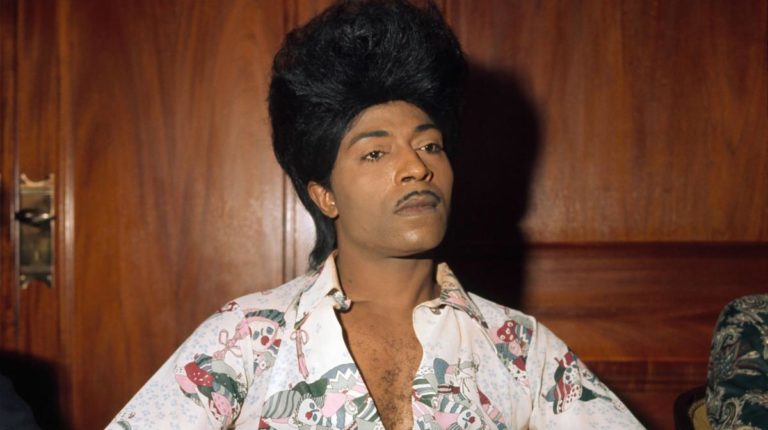

Richard’s seminal cultural benchmarks such as “Tutti Frutti,” “Long Tall Sally,” “Lucille,” resonated with audiences and his self-indulgent glitter jumpsuit, signature hairstyle, caked-on makeup became his touchstones. That made him so memorable.

The film addresses the many contradictions and agonies in the life of Little Richard, the man. Director Lisa Cortés manages to balance the exaggerations of his performance and suggestive showmanship, with the grievances of his treatment by the white musical establishment of the ’50s and ’60s and by the musicians who stole his material — as he often had said had happened to him.

Cortés doesn’t cross-examine her celebrity contributors on the appropriation matter too deeply. She leaves out the complicated layers of her subject’s private life and some of his run-ins with the law, such as when Richard enrolled in Oakwood College to study theology. The director makes it seem like Richard left the school because he married Ernestine Harvin. In reality, he was expelled for exposing himself to a male student. His sexual orientation was examined on a surface level. It presents Little Richard as, “a man very good at liberating people and not so good at liberating himself,” which suggests the shadings of tragedy.

The film raises fresh notions about the American mythology of rock music which suggest that the genre’s actual pioneers were black queer people, but it doesn’t tackle the matter of Little Richard’s male partners or his gay love life to the extent that the film addresses his period of heterosexual marriage and social life. Maybe Cortés couldn’t find or convince any of Richard’s male partners to go on the record about him?

Cortés infused with a fast and furious amount of archival imagery, iconic audio, flashes of footage offering a quick survey of the legend assuring us of his greatness. The director integrates Richard’s importance as a gay black man on the national stage, while reminding us that some of his songs are part of the soundtrack of our lives. In the end, Cortés’ documentary offers a greater appreciation of Richard’s hits, his innovations and unconventional character — even if Richard, the person, remains obscure.

Grade – B