Photo by Nobuhiro Hosoki, Director J.A. Bayona

Society of the Snow : In 1972, Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, which had been chartered to fly a rugby team to Chile, crashed in the heart of the Andes. Only 29 of its 45 passengers survived the accident. Trapped in one of the most hostile and inaccessible environments on the planet, they have to resort to extreme measures to stay alive.

Rating: R (Violent/Disturbing Material|Brief Graphic Nudity)

Genre: Drama, Adventure, Biography

Original Language: Spanish

Director: J.A. Bayona

Producer: Belén Atienza, Sandra Hermida

Writer: J. A. Bayona, Nicolas Casariego, Jaime Marques Olarreaga

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Release Date (Streaming):

Runtime:

Distributor: Netflix

Production Co: El Arriero Films, Apaches Entertainment, Cimarrón Cine, Benegas Brothers Productions, Telecinco Cinema

Photo by Nobuhiro Hosoki, Brian Williams, J.A. Bayona and Actor Enzo Vogrincic

Q&A with director J.A. Bayona and Actor Enzo Vogrincic Moderated by Brian Williams

Q: “Society of the Snow” was all shot in sequence, which is so rare now and shooting on location with all the challenges. How important was it to you to have an Uruguayan voice to this film, this passion in your life for the last decade?

J.A. Bayona: This story is not only well-known in the Spanish-speaking world, but also [throughout] the whole world. There are many documentaries about it. There were two movies already done, so we had to do this one right. We spent the time, and we wanted to shoot in Spanish. There was no way to shoot this film in another language than Spanish with a Uruguayan accent, since it was based on a book by a Uruguayan author with a Uruguayan voice and a Uruguayan actor. It took us 10 years to find the financing, find a place where we were allowed to show up and believe in the film, and believe in the level of ambition we were looking for, again in Spanish.

Once we knew the film was going to be done — actually before we knew the film was going to be done — we did auditions for nine months, looking for the actors. I saw 2,000 self-made tapes, and from those, I started to choose faces and meet actors online, because it was during the pandemic. We finally got our cast. That was at the end of 2020. We did two months of rehearsals — which is a luxury — maybe seven weeks. Then, all the cast met the real people they were portraying or the families of the dead. Then we spent a very long shoot, 140 days, which was extraordinary. We created such a beautiful family. Everything that’s in front of the camera was real. The friendship, the love, the sense of camaraderie, and we were there with our cameras. We captured that.

Q: Who was your continuity director? You’ve been recognized for makeup and hair. This was another-level continuity.

J.A. Bayona: I gave the actors a lot of space and freedom to improvise, because they were so well prepared. They spent two months in rehearsals, met the survivors, and read the book. They had all the information, and then they worked in similar conditions, with a context that was constantly stimulating the performance. There was a lot of space to improvise. We shot 600 hours of material. The heroes of this film are the editors, because they had to deal with that. There were a lot of continuity issues that we had to deal with in the editorial.

Q: Enzo [Vogrincic], when it comes to rehabilitation in the hospital, the showers, the emaciated bodies— and being a 2024 film realist — it wasn’t all body doubles that come along; your body weight went from 159 to 103 during the shooting of this film. That was real. How important was it for you, for the living and the dead, to honor your character?

Enzo Vogrincic: While we were making the film, as actors, we always thought we owed the people that survived, those that died, to tell their story as realistically as possible. Therefore, when we were filming things such as hunger or cold, we were barely able to move. It was a way of replicating what they had gone through, beyond our acting, because we knew that we had a responsibility to the people and to the character.

This was not a typical shoot whatsoever. It was part of the story, so fundamentally, we were willing to do whatever it took to get that realism in. After putting in 12 hours of filming and besides, we were eating very little, we found that we could set up a gym afterwards. At night, those of us who were not filming, we were training and continuing to lose weight.

Photo by QUIM VIVES/NETFLIX/QUIM VIVES/NETFLIX – © 2022 Netflix, Inc.

Photo by QUIM VIVES/NETFLIX/QUIM VIVES/NETFLIX – © 2022 Netflix, Inc.

Q: Enzo, how important was it to you that this project be delivered in an Uruguayan voice?

Enzo Vogrincic: This is something that was fundamental to us, because this story has been told before, but has not been told with our voice. I thought that was the key thing to do because, though some theories say we are human regardless where we took place, these were the stories lived and survived by Uruguayans. We thought that to be able to tell it in the original language, it was important for us to understand the tales of the survivors, and to be able to tell the story better. There were terms, feelings, and all those things which mattered, because it hadn’t been done that way before.

Q: Juan Antonio, there were scenes that involved faith, the notion of a higher power, permission from God; on the other hand, what kind of God would allow this? Those scenes were directed with great care. Tell us how you approached that?

J.A. Bayona: I always try to be as close as possible to the characters, to the reality, in order to be able to capture them with a sense of authenticity, a sense of place, of being there. And these guys were, most of them, very religious — there was a lot of religious iconography. I like to think the film tries to be more spiritual than religious. I see them like orphans, abandoned in a place where life is not possible, and they need to reinvent life.

They need to, somehow, reconsider what is important and what is not, as human beings. By doing so, the movie becomes a mirror of ourselves. They had to start everything from scratch. They were abandoned by the authorities, they were abandoned by their families, so they had to. For them, it was a journey of self-discovery. It was also a way of understanding that God was everywhere, in order to survive.

There was not a religious institution in the middle. When we mention cannibalism, when we talk about it, that’s a word that they don’t like to use. I think this film makes a big change in terms of that it’s not about taking, it’s about giving, about giving yourself to the others and suffering the same pain that the other ones are suffering. By doing so, feeling empathy, and by the understanding that you, and the person in front of you, are the same thing.

It’s like when Gustavo Zerbino told Roberto Canessa, “You have the strongest legs, you need to walk for us.” [And he did until they were found, saving everyone who remained.] There’s an immediate realization that you and the other ones are the same. We are all the same. To me, that feels sacred, spiritual and transcendent.

To understand that we are all part of the same thing, that resonates in the world we live in right now especially with young people. We are surrounded by so much conflict, and finally having this story that tells you that we are all part of the same thing, that we are all on board of the same plane. We need to come together to find a solution. We had such an important message that was our fuel.

Q: With today’s GPS, the flight would have landed at its destination safely, one would hope. You had to get the technical details right. The formal report said it was pilot error. That’s clear from your work. How challenging was that, starting with your visit to the crash site?

J.A. Bayona: We had to give the context to make others understand what they went through, and by doing so, what they did. We put so much effort into all details, like talking about that type of plane. We went to the Uruguayan Army. We had a very honest conversation with them. They accepted that it was human error. But it was actually a combination of human error with some kind of an early model of GPS that failed that day.

They basically had to do this turn there because that kind of plane was not able to fly at 40,000 feet. So they had to go through this lower pass. And they had to do this kind of U-turn. It takes 20 minutes to get from one side to the other. But they turned to the right only when they were six minutes into it.

That’s why it’s considered to be a human error because there was no way that the pilot didn’t know that. The pilot did that journey many times. But we really don’t know what really happened in that cockpit. I decided to leave the camera outside of the cockpit out of respect for the pilots. We knew that there was a machine that failed there. But anyway, we decided out of respect not to get into that space and stayed with the other characters.

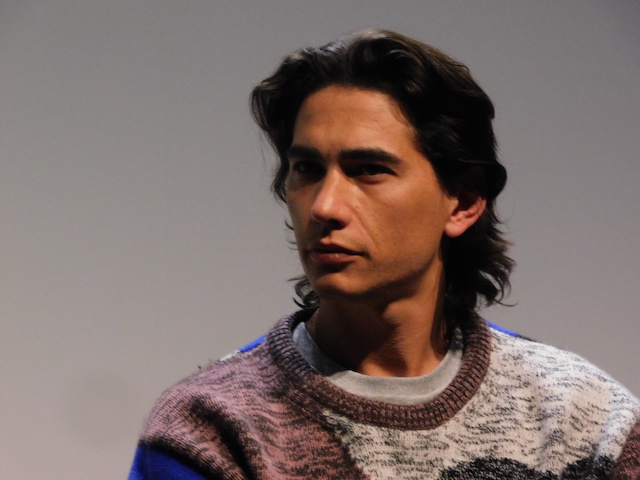

Photo By Nobuhiro Hosoki, Actor Enzo Vogrincic

Photo By Nobuhiro Hosoki, Actor Enzo Vogrincic

Q: Enzo, will your life ever be quite the same after the experience of filming this movie?

Enzo Vogrincic: In life everything that you do changes you. I think that you are never the same after an experience this informative. Of course, I’ve changed. I am different, I like to take every opportunity to continue changing myself. The biggest changes were on a professional level and in terms of how much I learned. I had to go in depth into my character and we spent one to three years with those people talking about life, death, friendship, love, family and making friends. I’ve made 25 new friends and therefore I like to think that I did change.

Q: Juan Antonio, talk about your immersion in your new extended family. The family of the living and the family of the dead.

J.A. Bayona: I sent an email to the survivors in 2011 and in that first email, I already sent a line about Roberto Canessa that said, “Talking to the dead, he says, accepting peace, that we have the chance to live the lives we didn’t have the chance to live.”

I was very struck by that conversation between the living and the dead and that sense of depth towards the dead. The more I got in contact with the survivors, the more I talked with them. The more I realized that they needed the film even more than me. They needed the film to be done more than me.

My big question was what was left after so many documentaries, books, and movies. Then I realize now, when I see the film with them, that it was not about telling something that wasn’t being told yet. It was more about giving them the chance to say thank you to those people who were so important. I see how it was like a poetic thing, the fact that people who didn’t make it, they gave everything they had for these people to be alive.

And now they are using their testimony to bring these people back, to keep them alive again on the screen. By doing so, I realized that they were comfortable with the story. So it was more about finding the chance of these guys saying thank you to these people and capturing the mood and the feelings and the emotions and the context of what they went through so people in the cinema would be able to understand what they did.

Q: In the hands of another director, the debate over sheer survival might not have been handled as beautifully as you did. There’s a line in the script, where Enzo says, “What was once unthinkable became routine.” There’s a shot, as the black & white photos are being taken, showing a human rib cage, almost cavalierly, to keep it out of the pictures. The pictures, of course, are still with us today. They’re on the web for people to see. You’ve managed to take on such a life-and-death topic and deal with it matter-of-factly but with great respect and discretion.

J.A. Bayona: I’m so glad that you asked about that line because that’s life. That’s life. First, you do what you think is impossible, then you get used to it, and then there’s a moment that you don’t pay attention to it. Our ordinary lives are about that. These people remind us how important every single detail in our life is.

It doesn’t matter if we are black or white or if we are American or Spanish. We have our chance, which is the chance of living life. But when you meet these guys, you meet people who have that chance to live. That makes a big difference. This is when you realize that sometimes we kind of are complaining or you’re not appreciating, you don’t realize that you have a life.

Photo by QUIM VIVES/NETFLIX/QUIM VIVES/NETFLIX – © 2022 Netflix, Inc.

Q: Enzo, how cold did it get? At what altitude did most of the filming take place?

Enzo Vogrincic: Well I have to admit, it was hard to tell this story. You feel you have to go through the pain that you do in order to tell it well. The shooting was hard. Obviously it was hard because you have to connect the pain with your body, we had to lose weight and experience cold. You have to do it until the body becomes part of that character’s story.

There were experiences that allowed us to feel the pain, we were able to work less on certain things and still retain the emotional tone of the story. The emotions didn’t take over necessarily when you had to suffer in your body and there were other important components to it as well. In addition to the pain and the suffering. You were able to see that you had a duty to carry out and that took you beyond the pain because you had to tell the story in a competent way.

J.A. Bayona: Let me add one story. Enzo did such an extraordinary job. He was so committed to the performance of Numa that when we finished the shoot we had to go back to the Andes because the first time we went, there was very little snow because of global climate change. We went for one year. Once we finished the shoot, we went back there to shoot again in the background.

Secretly he was in Uruguay and I called Enzo and said, “What are you doing next Wednesday?” he said, “Nothing.” I said, “I want to take you to the actual place where the plane crashed. I don’t have permission from the other producers but I think I can manage to bring you there. How much is the ticket?” He said, “$400.” I said, “well, we can pay $400. I can talk with the insurance company and the professional drivers.”

I secretly took Enzo finally with the blessings from the other producers just because he did so much. We had this shoot then we had the person in Germany that was to do this film. I really wanted Enzo to be there and be able to shoot some shots that were very helpful for the film. You can treat the audience by putting in a couple of shots of Enzo there and there. At the same time, Enzo had a closure to that journey.

He was able to do these shots, but was also able to stand in front of the great theater. I don’t know what you said there, what you did there, but you had your moment there. to me that was very important. When you do a film, the whole atmosphere affects the final result. I pay attention to these kinds of details. Also, I wanted him to be there and have that closure.

Q: Having just shared this [in a theater is] what movies are designed for, communal viewing experience, but when someone watches your movie on a [streaming device], how does it affect you? To be honest, can you interpret it for any language that it needs to be interpreted for?

J.A. Bayona: Can we take the Netflix people out of the room for a second? No, listen, we spent 10 years trying to take the financing for this film. we tried to do this film by conventional windows to the cinemas. Apparently there is no market for Spanish films that are over $10 or $15 million in budget. We couldn’t do this film with that budget. We spent 10 years and when we were about to give up, Netflix showed up and put in the money and gave us the freedom. They made the film possible.

At the same time, I come from Spain. To me it’s more difficult to handle the market in the US than in Spain. I’m quite popular there. We released the film on December 22nd. It was a limited release, 100 cinemas. Normally one of my films would be in 500 cinemas. We released the film in 100 cinemas. I decided to go with the film. Every week, I went to a different city and showed the film.

The film is still in the cinemas, in the same number of cinemas. We’ve done 100 million admissions. The film actually is doing better since it’s on Netflix. I’m very happy that Netflix made the film possible and made it accessible to the whole planet. We had 100 million people watching the film in the first 10 days. So it’s not true. There is a market for Spanish films. But also I’m glad that the movie is still in theaters for people who want to see it there.

Photo by Nobuhiro Hosoki, A Survivor Gustavo Zerbino and J.A. Bayona

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.